Surely one of the most moving thanks ever penned for an act of botanical patronage was that written by Archibald Menzies from his surgeon’s post on HMS Assistance, from Halifax, Nova Scotia (known to the French as Acadia) on 30 May 1784. It was addressed to John Hope who had recognised the talents of a Perthshire boy, trained him as a gardener in the Leith Walk incarnation of RBGE, and paid for a medical training that allowed a profitable medical career, initially with the Royal Navy. Here is what Menzies wrote:

In this situation the tears trinkled down my cheeks in gratitude to you Sir, who first taught me to enjoy those pleasures which providence has so conspicuously placed before my eyes, accept of them as the only mark a grateful heart can at present offer.

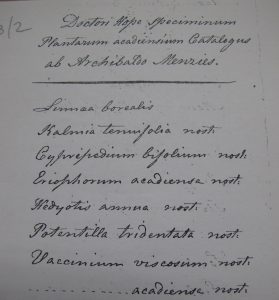

This first ‘mark’ of young Menzies’s thanks was botanical, in the form of a collection of seeds collected in the West Indies and near New York. Sent with his next letter, of 2 November 1784, were seeds and dried specimens collected in Nova Scotia, with an accompanying list of the specimens. Nobody knew that any of these had survived, as Hope’s herbarium has generally been taken to have disappeared.

On Wednesday Deborah Reid asked to see me about the Canadian herbarium of Christian Broun Dalhousie, one of those discussed in her fascinating recent PhD dissertation on Scottish women gardeners and collectors. Lady Dalhousie was wife of the 9th Earl, a soldier and administrator who was Governor of Nova Scotia from 1816 to 1820 and Governor General of British North America from 1820 to 1828. She gave her later Indian collections to the Botanical Society of Edinburgh and these, with their enigmatic ‘CBD’ labels, are a well-known element of the RBGE herbarium. Much less is known about her Canadian specimens, but it emerges that she must have sent these to the Edinburgh University Museum shortly after 1824. Given that our collections are arranged taxonomically, the only way to find specimens made by a particular collector is to think of a species they might have gathered and visit the appropriate cabinet: my favourite sport of herbarium angling. I thought of an obvious genus – the ladies slipper orchid Cypripedium – we went to the ‘Area 13’ (North America) cover in the family Orchidaceae, and within minutes had found a Dalhousie specimen of C. acaule.

Interesting enough, like two Desmond Morris biomorphs engaged in conversation, but what really set my heart racing was the sheet next to it. An exquisite specimen collected by Menzies, with two detailed manuscript descriptions in his beautiful copperplate hand. This led me to the copies of Hope’s papers in our archive (the originals are in the National Archives of Scotland), and I found not only three letters that Menzies wrote to Hope in 1784 and 1785, but the list of accompanying specimens. Hope had recently sent out to Menzies a copy of the 12th edition of Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae, from which he concluded that seven of the 41 specimens (5 cryptogams, 36 flowering plants), were new and undescribed species. Conditions for a scientist were terrible and Menzies told Hope he had

examined & described [the specimens] with candle light in the centre of a noisy cockpit which is my station on board.

The new ones were marked on the list ‘nost.’ (nostri = ‘ours’). With the list in hand, I went to the various cabinets, and was able to find specimens not only ALL the supposed novelties, but five of the others on the list, and four previously unknown specimens from Menzies’ next expedition of 1786–9 to the Pacific North-West. When Menzies died in 1842 (aged 88) he left his own herbarium of monocots and cryptogams to Edinburgh University, and I also unearthed a duplicate of one of the 1784 Nova Scotian specimens in his own collection, still unidentified after 230 years.

The interest of these specimens is huge, not least as they show what an acute botanist Menzies was, despite the grimness of his botanical laboratory. Of the seven supposed novelties only one had already been described (for this Menzies had looked in the wrong genus: it was a Houstonia rather than a Hedyotis, already described by Linnaeus in Species Plantarum as Houstonia caerulea), and if Hope had been a better taxonomist, a more prolific author, or generally quicker off the mark, he could have described six new species on his pupil’s behalf. What Menzies proposed to call Cypripedium bifolium, Eriophorum acadiense, Kalmia tenuifolia, Potentilla tridentata, Vaccinium viscosum and V. acadiense, were named by later authors respectively, as: Cypripedium acaule (by the Kew gardener William Aiton in 1789), Eriophorum tenellum (by the American Thomas Nuttall, but not until 1818), Kalmia polifolia (by the German Friedrich von Wangenheim in 1788), Potentilla tridentata (by Banks’s librarian Daniel Solander in 1789), Andromeda (now Gaylussacia) baccata (Wagenheim, 1787) and Vaccinium macrocarpon (Aiton, 1789).

The plants themselves were not only of purely botanical interest, the last one being the edible cranberry (that has been improved by cultivation). But the final significance of the specimens is that they confirm my suspicion as to the fate of Hope’s herbarium. The collection was Hope’s private property and accordingly removed with all his books and papers following his death in 1786. The specimens, however, were later returned to RBGE by his son Thomas Charles Hope, after which they went ‘missing’. The present RBGE herbarium dates from the mid-19th century, the result of the combination and recuration of the old University collections (which included the Dalhousie Canadian specimens) with that of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh (largely British, but including Lady Dalhousie’s Indian plants), and which was housed at RBGE by about 1860. By finding the occasional Hope specimen on sheets assembled in the mid-19th century (usually with specimens from later collectors and localities – it was the SPECIES that was important rather than its provenance), I had come to realise that most of Hope’s specimens had probably been discarded in the re-organisation – perhaps they had been badly chewed by insects or suffered from damp; and the British species would have been duplicated in large numbers by better and more modern material. These Menzies specimens prove that this is indeed what happened, many of them being mounted on sheets along with later specimens – the backing sheets are various: two have a watermark of 1848, and two of 1860. Hope’s herbarium sadly does not sit languishing in a closet or loft awaiting rediscovery. Small as this Menzies collection is, it represents one of the largest surviving fragments of Hope’s herbarium, along with a much more extensive set of specimens sent to him by Adam Freer from Aleppo (but that is for another Botanics Story).

Dora Thornton

Happy herbarium angling —but you only see what you already know, so most of us would never make such discoveries. It takes a Dr Noltie.

anne noltie

Fabulous research.

What a reward for diligent work.

Fascinating to read of the Halifax find,

Ann Noltie

Maura Flannery

I am a fan of your work, and this is a wonderful example of what you unearth, and how well you write about it. Thank you.