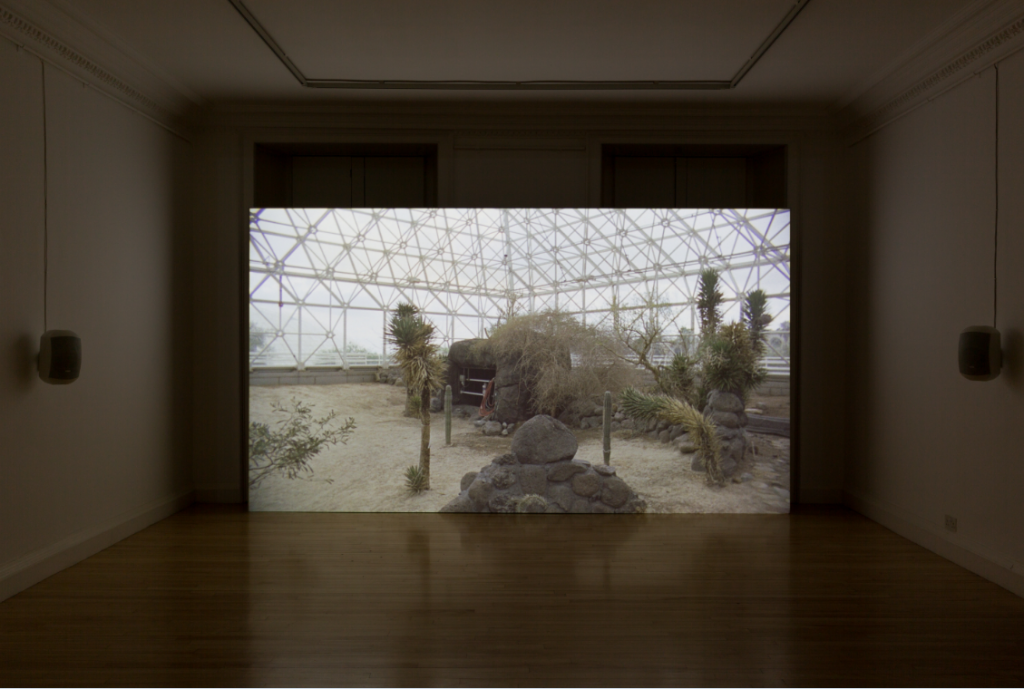

Ben Rivers, Urth, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry, London

False Habitats and the Twisted Threads of Fate[1]

Buildings almost always outlive their makers; and they lead strange and wonderful afterlives, doing all sorts of things they were never designed to do. Products and objects migrate through cultures, places, and times, and their meaning changes as they are used again and again. In this sense buildings and products tell their own stories; but, more interestingly, they are also like stories, handed down from generation to generation, from place to place, altering subtly as they go.[2]

Ed Hollis

We living things are the ghosts. The architects were correct; we are only our monuments.[3]

Female protagonist in Urth

Worldmaking as we know it always starts from worlds already on hand; the making is always a remaking.[4]

Nelson Goodman

Ben Rivers, Urth, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry, London

Ben Rivers, Urth, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry, London

In 1991 a former ranch in Arizona- turned corporate conference centre in the 1960s – was ready to be inhabited by a group of scientists in its latest incarnation, as a centre of research for the development of a self-sustaining, artificial ecological system. Sealed from the outside world by steel and glass, the stories of the Biospherian’s, who temporarily lived and researched in the structure as part of a series of experiments, exist in widely varying accounts after the fact that include anecdotes about the lack of food and personal disputes.[5] Although the self contained eco-system in Biosphere 2 was a short lived fantasy the building itself remains and is now owned by the University of Arizona who use the space with a view to investigate how climate change will impact the Earth.

Plant Scenery of the World at Inverleith House is delighted to present the UK premier of Ben Rivers’s film Urth (2016) as part of this group show that explores the ideas of re-created worlds, false habitats and imagined narratives around utopian and idealised displays of plants under glass. Urth, which was filmed inside Biosphere 2, once again re-imagines a purpose for this glass structure in the near future. Using documentary tropes and storytelling devices, Rivers’ female protagonist describes what she claims are her last days on Earth. She is trapped in this curious, artificial structure that contains the ocean, the jungle, the desert which all have an uncanny resemblance to life on Earth, but are at the same time void of life, wind and oxygen. River’s practice is influenced by the work of Nelson Goodman, who argues that art, philosophy and science all make statements in relation to ‘the nature of reality through the creation of “worlds”; these worlds may be simultaneously true and yet incommensurate.’ [6] As Urth’s last woman, the narrator dutifully reports her pseudo-scientific findings that get progressively less optimistic each day, echoing contemporary concerns about the futures of our own eco-systems and societies.

The histories and subsequent ‘afterlives’ of buildings also fascinate our special guest Ed Hollis, whose book The Secret Lives of Buildings aligns with the themes of imagined futures and worlds through storytelling and worldmaking that run through Plant Scenery of the World. Ed’s research is focused on how buildings shapeshift over time and to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Front Range Glasshouses Inverleith House presents a one-off tour of the Glasshouses at 3pm on the 21st of October. Drawing on diverse influences and stories, Ed will bring the microcosm of the glasshouses and the imaginary worlds they contain to life. Book tickets now via Eventbrite!

Join us also on Wednesday the 25th of October for The Front Range Turns 50 Celebrations where we will be in the Glasshouses doing a drop-in bag making workshop for all ages!

[1] Ben Rivers’ film Urth takes its name from the Norse word for the twisted threads of fate as cited by Timothy Morton in Dark Ecology.

[2] http://www.edwardhollis.com/page13.htm accessed 30/09/17

[3] Quote from the film Urth (2017) by Ben Rivers, script written by Mark von Shlegell.

[4] Rivers, B. and Steinbridge, B. (eds), Ben Rivers Ways of Worldmaking, Mousse Publishing, Milan, 2016, p9

[6] Rivers, B. and Steinbridge, B. (eds), Ben Rivers Ways of Worldmaking, Mousse Publishing, Milan, 2016, p9.