This is the second post in a series about the Taxon Name Linking Service project.

The process of combining biodiversity data from multiple sources currently starts with matching of the Latin name for the organisms used in each dataset. Studies often contain names that can not be unambiguously matched or miss out some names entirely. Typically when combining two sets of data, between 10% and 20% of names will fail to match unambiguously and may need some human interaction or lead to errors. This didn’t used to be a problem because humans were doing the work. In fact it was much of their work. Did the author of this book mean the same thing as the author of that paper?

Today we have greater expectations of what should be automated. We expect computers to combine data containing many thousands of names in ways that would amount to a lifetime’s work if done by hand. Consider two lists of one hundred names each. That might reveal ten names that are problematic and take minutes or hours to clarify. But if the lists contain tens of thousands of names the problematic names thrown up might take weeks to resolve. Each time more data is brought into a study then the name matching process will throw up more ambiguity to be sorted by weary humans.

Surely if we use the scientific names for plants correctly this shouldn’t be a problem. Alas there are many ways in which scientific names are not used correctly, every four years or so we change the definition of “correct” and even when they are used correctly they can still be ambiguous at a global scale.

Over the next few posts in this series I will go into some of the ways Latin names can be ambiguous but here is an example from today’s list. The name “Cyathea bünnemeijerii v.A.v.R.” appears in the current Flora Malaysiana website. It contains a umlaut over the “u” which the International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi and Plants now says should be replaced by “ue”. Diacritics are not permitted in plant names. But that was not the case in 1922 when the name was published by Cornelis Rugier Willem Karel van Alderwerelt van Rosenburgh. No wonder his name was abbreviated! The standard abbreviation in IPNI Authors and Wikidata is “Alderw.” not “v.A.v.R.” but the standard forms of author abbreviations were only introduced in 1992 by Brummitt and Powell, some seventy years after Cyathea bünnemeijerii was published. The correct way of writing the name of this Indonesian tree fern today is Cyathea buennemeyerii Alderw. but biologists recording observations and labelling specimens over the last one hundred years may have legitimately used different spellings. Even if nobody ever made a spelling mistake it would still be a challenge to automatically combine historical data based on the name used.

This situation is not unique to biology. There are parallels in many areas. A good example is the citation of other works in scientific journals. Each journal may have its own style of abbreviation. There are a few well known ones from major publishers, such as APA, MLA or Chicago/Turabian, that are adopted by universities and smaller publishers but it is a challenge to have a machine perfectly, reliably read these citations and link to the correct paper. Publishers therefore came together to use Digital Object Identifiers (DOI) for publications. These are identifier codes that uniquely distinguish the work and go alongside human readable citations. The readable citation can be in whatever form is most appropriate for the context but a link can always be made to the original work. A similar approach needs to be taken with organism names. Data should be tagged with unique, centrally managed IDs as well as traditional Latin names. In the World Flora Online Cyathea buennemeyerii Alderw. has the ID wfo-0001255235.

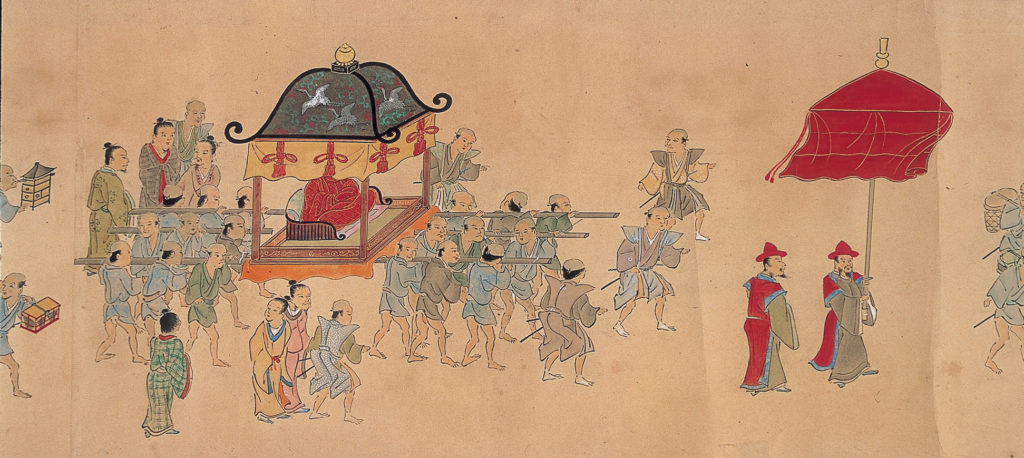

I travelled to Japan (virtually) to present at the SPNHC-TDWG 2024 conference on Okinawa on this subject. You can watch the full talk in the YouTube clip below, indeed the full session is on YouTube. There were people from around the world who work in the field present (both physically and virtually) so you may be interested in the other talks in the session.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation programme within the framework of the TETTRIs Project funded under Grant Agreement Nr 101081903.