The title is somewhat clickbaity but probably correct.

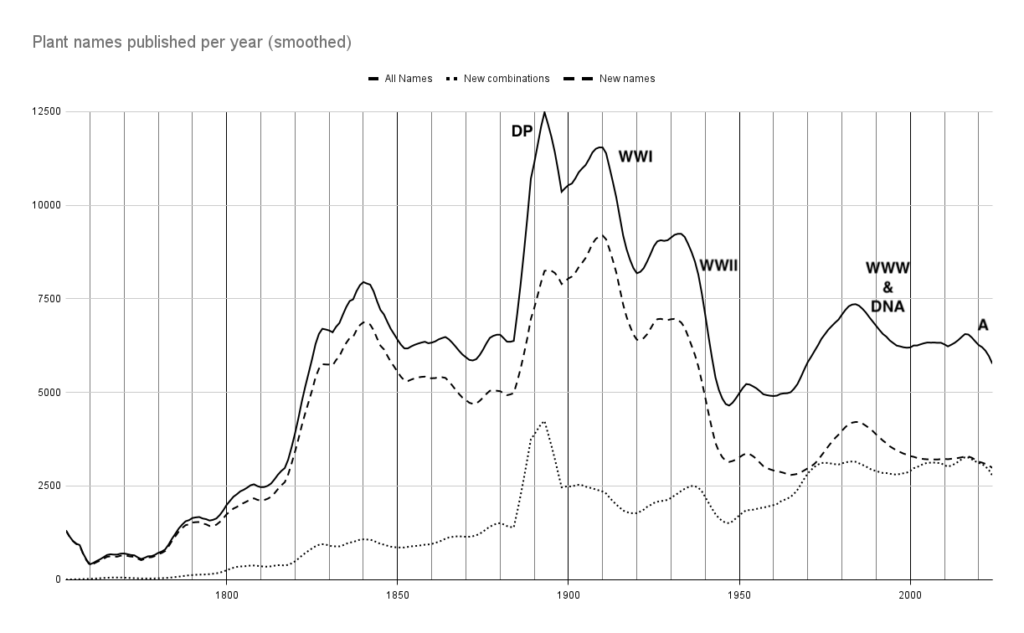

Working on the World Flora Online Plant List means we are continuously processing and reprocessing a list of all known vascular plant and bryophyte names. There are nearly 1.7 million of them and around 400,000 accepted taxa in our database. Something I’ve wondered about is how the publication of names is distributed through time. Are we publishing more names now than twenty, fifty or even one hundred years ago? Because we have all this data to hand I can answer the question with a simple database query. The answer is shown in the graph below and I think it is no.

Now you have seen the graph and know the answer you should be aware of the caveats. We have a field on each name record for the year of publication. Around 1.58 million (93%) names have this field filled in. Are they correct? Probably or as near as we can tell. If you’d like to work through them all and check we’d be most grateful! This is a smoothed graph. It is the average of a nine year rolling window. From year to year the number of published names varies quite a lot. A graph of the actual year numbers is much more spikey and hard to interpret. This graph gives a good indication of the trends. The dotted line marked as new combinations is actually the names with parenthetical authors and the dashed line is the names that don’t have parentheses in their author strings. Our coverage of homotypic relationships between names is incomplete and without it we can’t detect replacement names. Indeed we don’t know how to find out how many names might be replacement names without manually researching them all. The dotted and dashed lines should therefore be taken as indicative but with such a large dataset they are probably close to the truth.

I find this a fascinating graph to explore. There is the large bulge of description in the first half of the 19th century marking the age of colonial botany then a dramatic peak at the end of the century that I have marked DP for Das Pflanzenreich. There were other great synoptic publications in this period but Engler’s work seems to typify them. There are then the two precipitous falls in publishing rate coinciding with the world wars reaching a low at the end of the 1940s. Descriptions started to take off again by the 1960s peaking in the 1980s before flattening out.

Perhaps the most striking inflection point is in the late 1990s because it doesn’t exist! Indeed if you look at the last six decades (incidentally my lifetime) you could put money on the fact that between 5,000 and 7,500 names will be published each year and roughly half of these will be the result of new combinations. That is about 3,500 new species a year for over half a century during which time global population has gone from 3.3 to 8.1 billion, GDP has grown a hundred fold (28x per capita), we went to the Moon, Mars (virtually) and sent a probe into interstellar space. Perhaps more relevantly DNA sequencing became mainstream with Sanger sequencing available to researchers from the mid 1990s. We also invented the internet, digital imaging and GPS. This period even covers the invention of the actual microprocessor it is all based on (1971). We have also seen a large and welcome move of taxonomic work from Europe and North America to areas of high diversity, particularly in South America and East Asia. My new question is: Why don’t we see any of this reflected on the graph? Or do we?

There are some possible explanations that pop to mind. The data is smoothed and that might hide changes but the window for the algorithm is nine years so we would expect to see any trend over about five. The tail off at the end of the graph (A) is probably an artifact of the smoothing and the fact that it takes a while for names to make it into the database. But it could also be the start of a downward trend.

One might expect species discovery (and therefore name creation) to reduce as we reach an asymptote. We must eventually describe all the species or atleast have to expend more effort to find new ones especially as we are simultaneously destroying their habitats. Perhaps that is an explanation. Our technological advances are exactly compensating for the increased difficulty in discovery.

If these questions fascinate you, perhaps because my assertions are so outlandish, then I’d love you to produce some work of your own on the subject. The latest version of the WFO Plant List data is always available via DOI:10.5281/zenodo.7460141. New versions are released on the summer and winter solstices. If you aren’t up for some heavy data analysis and theorising I hope I’ve at least given you something to ponder over the Christmas and New Year break 2024/25. That is the great thing about blog posts. You can raise discussion points and hopefully trigger a debate that leads to more considered publications by someone else. Merry Christmas!

Max Coleman

Roger, that’s a very interesting observation. Surely, the limiting factor in the rate of species discovery is the number of taxonomists. Within the biological sciences only those with taxonomic training are likely to publish new species and new combinations. If the number of taxonomists is going down, as I think it is, then no technological advancement is going to have much impact on the rate of publication. We need to train and employ more taxonomists!

Max

Roger Hyam

Are you sure the number of taxonomists is going down globally? Sure in Europe (where there are few species to discover) it has been but there have been increases in other regions. The Flora of Brazil claims it has 1,000 taxonomists contributing to it. If that includes every taxonomists in the world (highly unlikely) then the rate of species discovery would be about 3.5 per taxonomist per year or 7 nomenclatural acts per year.

We need a graph of the number of working taxonomists by year but I guess that would be harder to produce than this one.

Max Coleman

A good point. My claim that numbers of taxonomists is going down is merely a hunch and I would be very interested to know what the true trend is…

Max