As a Gallery Volunteer it has been my privilege to spend a good number of hours looking at the diverse range of objects in the artist Siân Bowen’s exhibition After Hortus Malabaricus . I’ve also given some short talks on the exhibition based on what I have learned from the artist and my own observations and thoughts. So this is my take on it.

The exhibition looks at a particular set of Indian plants in new ways. In doing this we can better appreciate the nature of the plants, and also what meaning we take from the different ways they are represented.

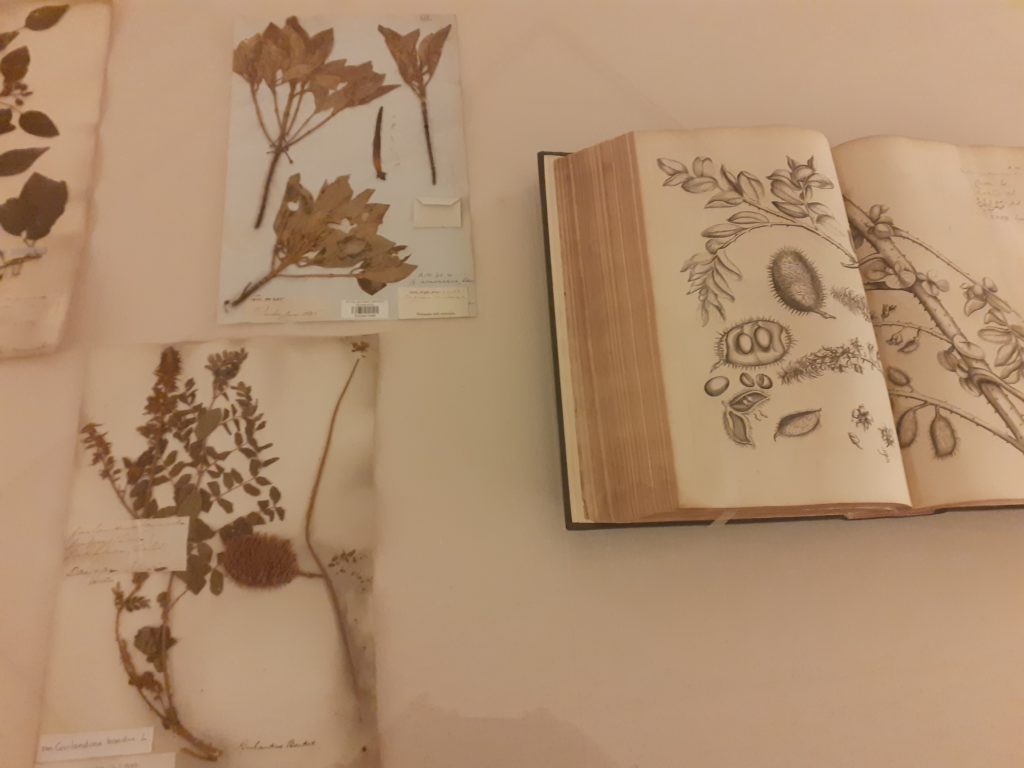

The main starting point for Siân Bowen were lovely old books from the Botanics’ Library and archives. They date from 1678, but took over 20 years to put together. These are some of the volumes of Hortus Malabaricus – which recorded plants thought to be medicinal, found in the Malabar coast region of India, which pretty well equates with modern-day Kerala.

The herbarium specimens were one of the other main inspirations for the artist. Each of the three you can see displayed in the exhibition relates to one of the illustrations shown alongside them. Siân deliberately did not include the names of the plants she depicted in her art, as she wanted people to concentrate on appreciating each representation for what it is. She hopes that you will look closely, when that is required. However, she did include a list of the scientific names on the wall at the top of the stair on the first floor. All the plants she used had been identified as endangered or at risk as species in the wild by the Indian botanist K.S. Manilal, who studied the Hortus Malabaricus and translated it into English in 2003.

I have a background in biology, and with that, part of me has a desire to know the names of what I’m looking at. You can see the names of three of her plants in the books and display cases. In fact, lots of names. The books often feature the scientific name alongside the common name in Roman/ European script, Arabic, and at least a couple of the local languages of Malayalam & Konkani. Sometimes a Portuguese name features in the book as well.

Names give an identity to a plant and a way of explaining to someone else what it is. The herbarium specimens also have a bar-code as a more modern way of identification. Sometimes, even the scientific name of a species changes and that gets added. Other common names can be given and those may affect how we view a plant. For instance, one shown in the book and herbarium specimens, Guilandina bonduc, is also known as a nicker bean. That tells us that it’s in the bean family and, maybe, also makes us snigger a little. However, nicker comes from a Dutch word – knicker – meaning clay marble, of the kind you play with. In some places, the seeds from this plant were indeed used in games. This plant features in many different representations in the exhibition – bronze image on indigo paper, as translucent rubber cast between sheets of glass, and laser engravings on acrylic disc and paper (the latter illuminated from behind in the room with the books).

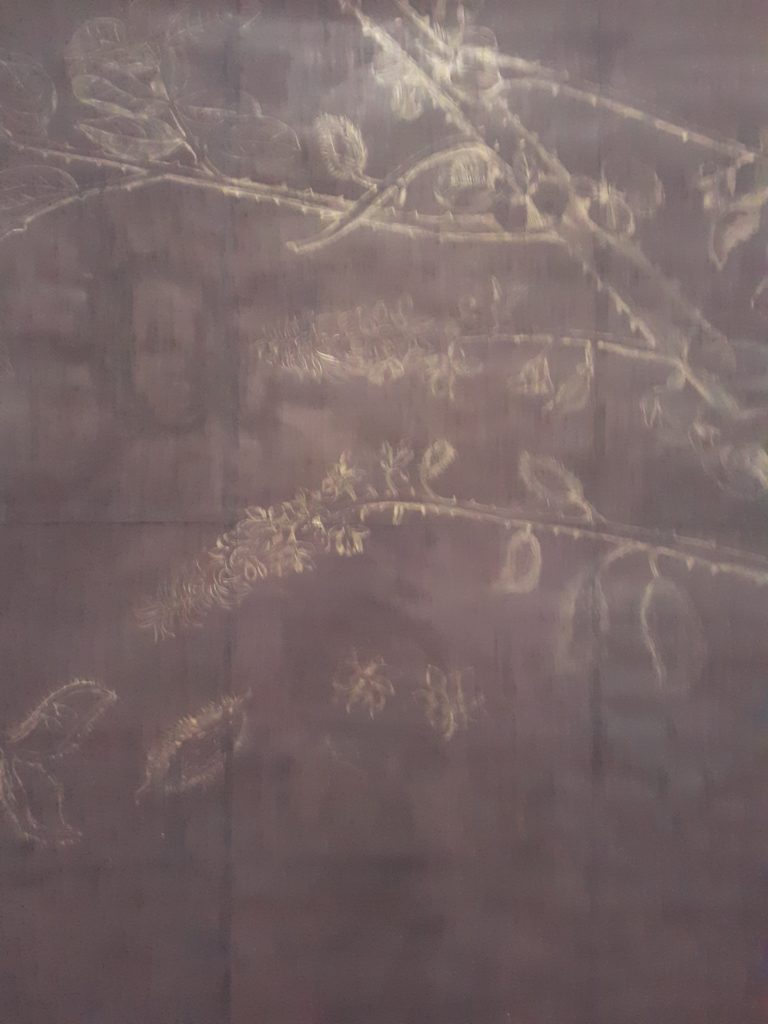

The artist used the original engravings from the Hortus Malabaricus as the starting point for some of her works, carefully copying them onto other media, like the acrylic discs downstairs and the bronze images on the massive shiny dark indigo paper. These giant images are among my favourites, often with a ghost-like quality of the images appearing and disappearing as you move around them or as the light changes. This echoes the precarious nature of these plants in the wild and encourages you to look closely and from different view-points.

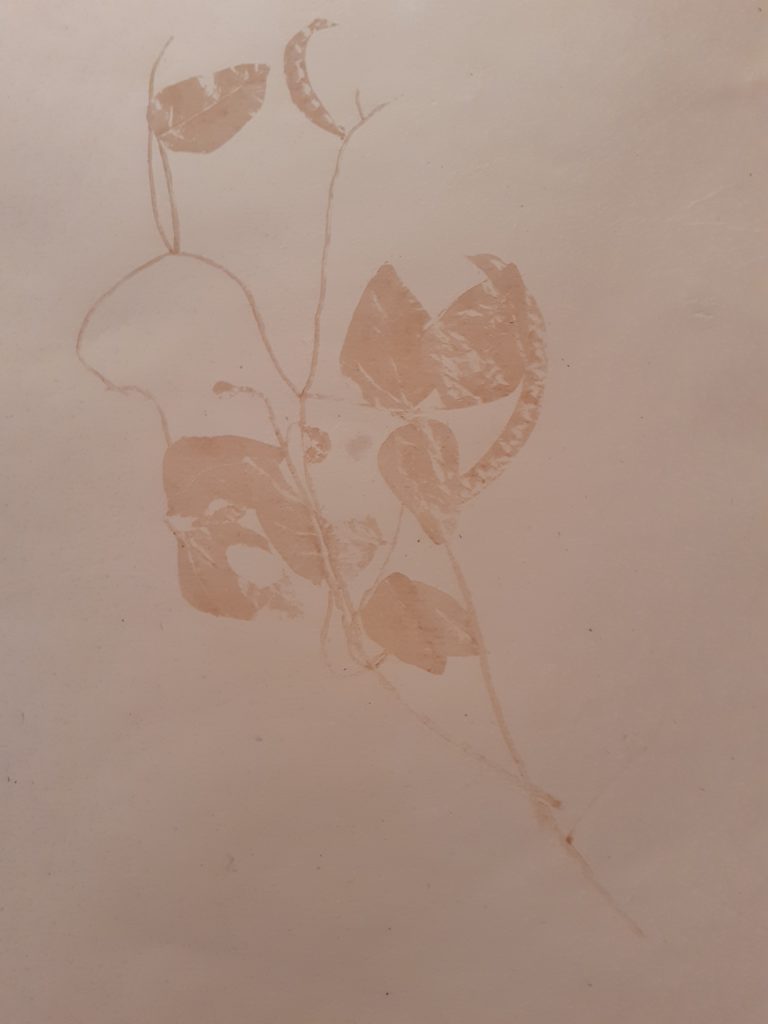

In other places Sian has used a laser to delicately engrave paper. This gives a sense of fragility that links to the delicate nature of these scientifically valuable herbarium specimens, but also to the endangered state, in the wild, of the 18 species that were her focus.

To avoid damaging the precious, fragile herbarium specimens, Siân created models of them to make moulds and casts for other depictions of the plants.

So from these starting points of book and specimens a whole wide range of representations of these plants was created to help us look at them in different ways. I’ve also found that the way the art works look changes with the time of day and the weather – and this adds to special nature of them.

A sense of place also enriches what we feel about these works of art and what has inspired them. So, to help us get that sense of place, Sian has created the soundscapes you can listen to downstairs and the videos on the first floor. These really do give us a greater appreciation of the other works of art, as well as being good to enjoy in their own right. The videos were made using old round Victorian mirrors to give a particular feel of tonal range and image shape. I think that concentrating on only one sense at a time helps us to focus on what we are sensing. These parts of the exhibition are particularly meditative, I feel. I also liked the echoes of the videos looking up at the different layers of the forest, in the multi-layered images created by stacking the engraved round acrylic discs.

If you haven’t been yet, you have until 22nd March to view the exhibition. If you’ve already been, then why not come again? – as, looking again, you will get the opportunity to see it in different lighting, in different ways. I have certainly appreciated After Hortus Malabaricus more and more as I have spent time with it.