At the Botanics we discover new species – it’s one of the things, in addition to growing plants and telling people about them, that we have been doing for a very long time. It’s our core business.

What many people don’t know is how little we know about species when we first discover them, and how long it takes us to make a start on understanding those plants better. Zoë Goodwin, ex-MSc student and now a post-doc at the Botanics, with colleagues at Oxford just published a paper documenting the time it takes to know the bare minimum about a species. In this paper we chose the point when there are 15 correctly identified herbarium specimens to indicate when we have a certain understanding of a species. There is nothing very special about 15, but it’s often the number required to make a reasonable attempt at conservation assessment to estimate the risk of it going extinct. How long does it take to know a species to that level?

Our answer is on average, 100 years.

Here is the story of one species and my part in that century-long journey.

This is Aframomum thonneri. It grows up to 5 m tall in the forests of central Africa. The purple flower that you see is about 15 cm tall. In addition to being beautiful, the flower is also incredibly delicate – the purple bits are as thin as tissue paper and start wilting as soon as you touch them. In the forest they last less than a day.

The rest of the plant is much more robust; fruits, leafy stems and underground rhizomes.

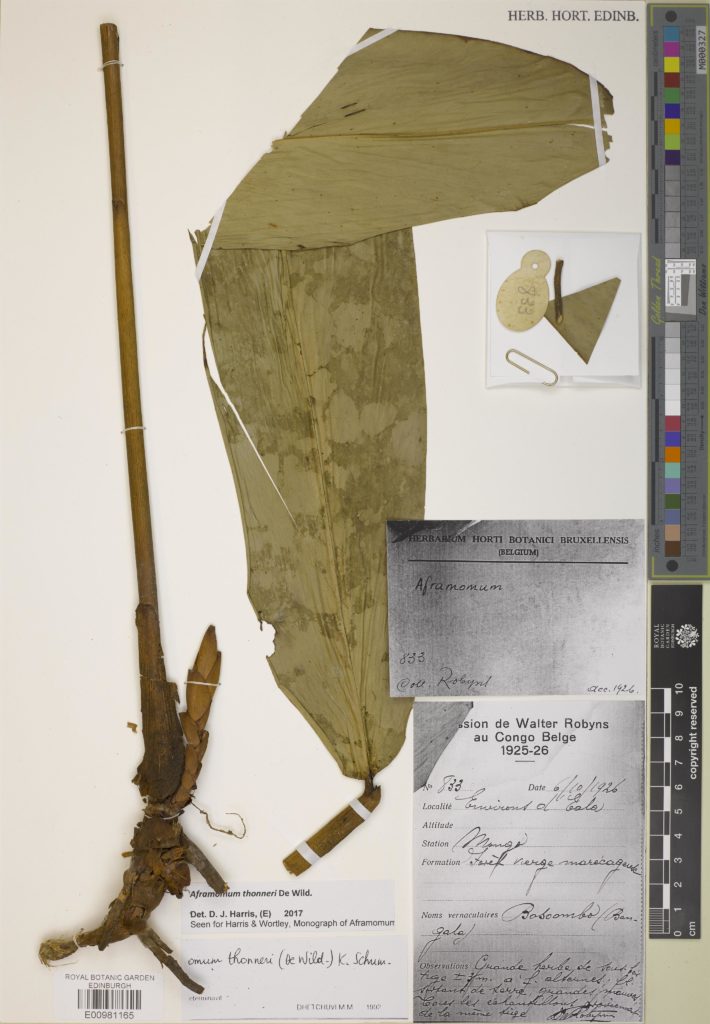

When it comes to making a herbarium specimen, we cut a part of the plant and dry it between newspaper. You can imagine which part survives – the leaves and the rhizome are as tough as old boots and survive the drying process. The exquisitely delicate flowers end up as just a dull smear on the paper. What this means is that the herbarium specimens of Aframomum thonneri like most in the ginger family make what you could call “poor specimens” – stronger terms are also available.

My fellow ginger specialists at RBGE can take hours to make good herbarium specimen. But when I first came into contact with Aframomum thonneri I was not an expert. I was part of a small team studying the ecology of the western lowland gorilla. In addition to identifying the food plants we were also trying, and failing, to habituate wild western lowland gorillas to our presence in order to study them up close. It’s a sweaty, dangerous job and it was just not for me. I did stick with being a botanist and 25 years later had the privilege of visiting these gorillas after they had been safely habituated.

Clump of Aframomum at the edge of a swamp Nouablé Ndoki National Park, Republic of Congo, with habituated silverback gorilla.

The gorillas eat a lot of Aframomum. I learnt to separate the 16 different species growing in the Dzanga National Park in the Central African Republic. I took those herbarium specimens to the world expert on Aframomum who helped me put names on about half of the species. For the rest of them I had to give them nicknames like “Aframomum common sp. 1”

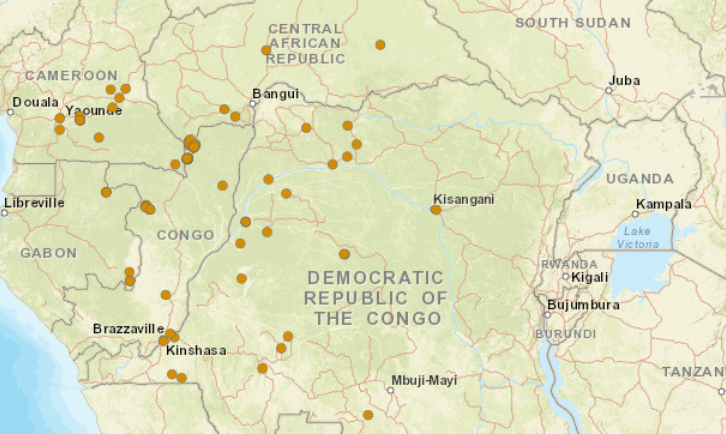

Aframomum thonneri was first collected in 1903 and the name was published in 1911 with only one specimen listed. The Belgian botanist describing the species did not have access to the other specimens or did not recognise them. The species was only know from the single specimen until 1955 when another specimen was collected and identified correctly. In 1992 my Congolese colleague Jean-Baptise Dhetchuvi during his PhD studies identified specimens collected in 1926, 1969 and 1975 all from the same species. At this point, 89 years after it was first collected the species was still known from only 5 locations in the Democratic Republic of Congo. When I was revising Aframomum with Alex Wortley – still with the Botanics, now on Science Policy – in 2009, I had that eureka moment. Looking at the original type specimen of Aframomum thonneri, I realised that it was the same as my Aframomum common sp. 1 which the gorillas enjoyed so much in the Central African Republic. Once I had made that connection, we went through all the similar looking specimens and found that it occurs in 5 different countries in central Africa.

The 15 specimen threshold was passed 105 years after its first discovery. The journey in our understanding of Aframomum continues.

References.

Goodwin Z.A., Muñoz-Rodríguez P., Harris D.J., Wells T., Wood J.R.I., Filer D. & Scotland R.W. (2020). How long does it take to discover a species? Systematics and Biodiversity https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2020.1751339

Harris D. J. & Wortley A. H. (2018). Monograph of Aframomum (Zingiberaceae). The American Society of Plant Taxonomists.