Henry J. Noltie

© The Linnean Society of London, photographed by Leonie Berwick

In 1805 the German botanical missionary the Rev Dr Johann Peter Rottler (1749–1836) intended to name a monospecific genus for Elizabeth, Lady Gwillim (1763–1807), wife of the Madras judge Sir Henry Gwillim. She was a talented watercolour artist, especially of birds, and a keen botanist who took weekly or twice-weekly botanical lessons from the man she variously referred to as ‘the German Missionary’ and ‘the German Botanical Doctor’. Rottler had moved from the Danish colony of Tranquebar in late 1803 to the Madras suburb of Vepery, as a missionary for the British Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK). Unless he published somewhere (such as an obscure German publication) as yet untraced Rottler apparently failed to carry out his intention. In London a few years earlier, in 1802, Henry Andrews had described the ‘dwarf magnolia’ Magnolia pumila from China in his magnificently illustrated Botanists’ Repository (volume 4, plate 226). When, in December 1806, John Sims figured M. pumila in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine (volume 25, plate 977) he had not only learned of Rottler’s plant and the proposed name, but (while paying due deference to Lady Gwillim) realised that it was nothing but a Magnolia and in fact Andrews’s M. pumila:

We have been informed that some Botanists in Madrass [sic], considering this plant as a new genus, named it GWILLIMIA in honor of the patroness of the science in that Presidency; but as it cannot be separated from Magnolia, unless the fruit should be found to be different, we do not feel ourselves at liberty to adopt the alteration, though desirous of paying every respect to this amiable lady.

Sims did not say how he knew of the South Indian plant or of Rottler’s intention but, from his use of the epithet ‘amiable’, it seems likely that he had seen the drawing, description and covering letter sent by Rottler to James Edward Smith the previous year (see below). (Both Smith and Sims had been botanical students of John Hope in Edinburgh though a decade apart – Sims in 1772, Smith in 1782). Rottler later sent a herbarium specimen, which is still in Smith’s herbarium at the Linnean Society of London, with the collection details ‘Gardens at Madras; plants brought from the islands of the East Indies’. Another probably contemporary specimen is in the Royle herbarium in the World Museum, Liverpool – it bears the name ‘Gwillimia indica’ in what is probably Royle’s hand, but no other details, and is likely to be one of the specimens from Rottler’s herbarium incorporated by Royle into his own while Professor of Materia Medica at King’s College, London, to which Rottler’s collection had been given by the SPCK. In terms of eponymy all was not lost, but the scene of action moves to Geneva.

In 1817 Augustin-Pyramus De Candolle (Regni Vegetabilis Systema Naturale, volume 1, page 455) published the name Gwillimia for a Section of the genus Magnolia. The section was created for the Asian species M. yulan, M. kobus, M. obovata, M. fuscata and M. pumila and, under queried generic placement, M. parvifolia, M. inodora, M. coco and M. figo. As Rottler had intended the name at generic rank it is superfluous (if not actually incorrect) to cite the sectional name as ‘Rottler ex De Candolle’, which should be attributed solely to the latter. In the same publication (p. 458) De Candolle cited the name ‘G. indica Rottler’ as a synonym of M. pumila Andrews, which means that the name was technically illegitimate and not validly published.

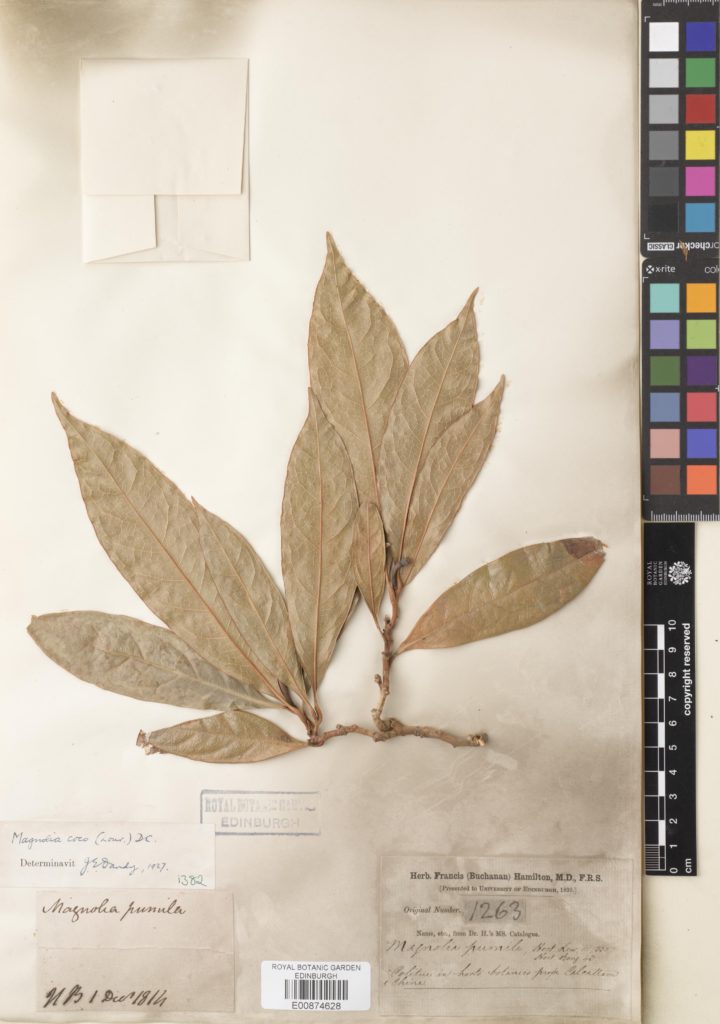

In recent botanical literature there has been disagreement over the correct name for Magnolia pumila. It is sometimes (e.g., in Kew’s ‘Plants of the World Online’) placed under M. liliifera (L.) Baillon, but is elsewhere (e.g. Flora of China, under the genus Lirianthe) stated to be a synonym of M. coco (Loureiro) De Candolle. Linnaeus’ Liriodendron liliifera (Species Plantarum, ed. 2, 1: 755. 1762), was based entirely on ‘Sampaca montana’ of Rumphius (Herbarium Amboinense 2: 204, t. 69. 1741) and Elmer D. Merrill in his Interpretation of Rumphius’ Herbarium Amboinense (p 224. 1917) considered the Rumphian plant to be Talauma rumphii Blume. The Linnaean species therefore cannot possibly be an earlier name for M. pumila. Loureiro described his Liriodendron coco from Cochinchina, Macau and Canton, published in 1790 (Flora Cochinchinensis p 347). Furthermore, whereas M. coco is placed in Section Gwillimia, M. liliifera is placed in Section (or Subsection) Blumeana. There is therefore no doubt that the correct name for Lady Gwillim’s magnolia is M. coco, as is confirmed by J.E. Dandy’s determinations on the authentic Rottler specimen in the Smithian herbarium.

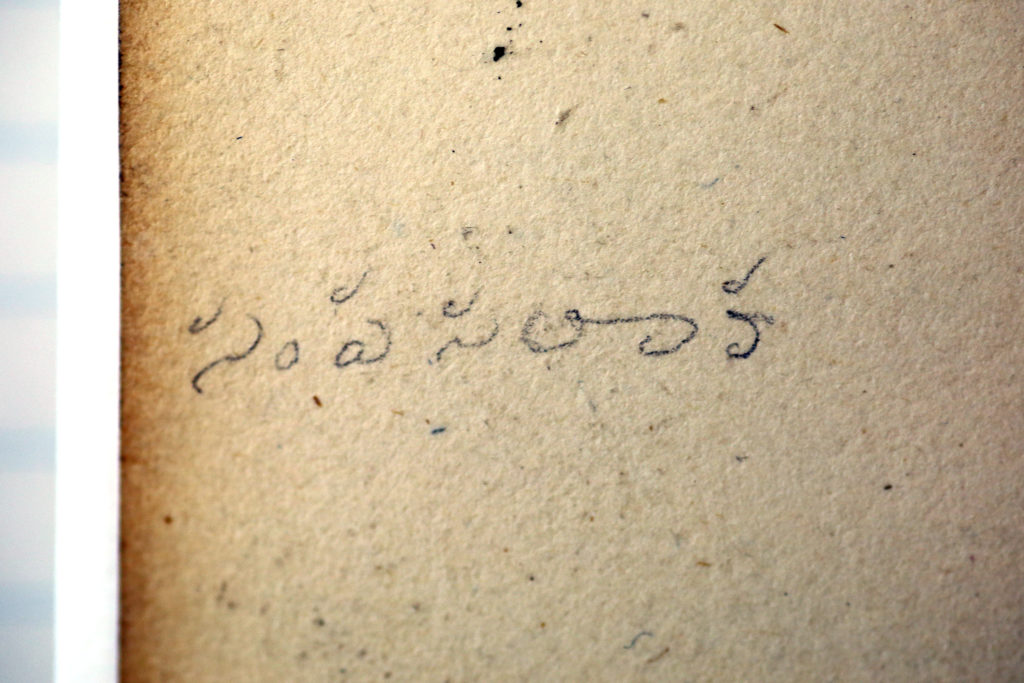

Although Lady Gwillim stated that the Madras plant came from Batavia (now Jakarta) it could easily have been cultivated there for its fragrant flowers and reached Java from China. According to Rottler it was cultivated in Madras in an ‘Armenian’ garden – most probably that of the house at St Thomas’s Mount which the Gwillims rented on several occasions from an Armenian. Lady Gwilim recorded that in Batavia the plant was ‘called sampa salaca – which means milk flower’. On the back of her drawing sent to Rottler, and by him to Smith, is a pencil inscription in Telugu script, which Gita Hudson in Chennai read as ‘sum pa sa la ka’, the name recorded by Elizabeth (and given that she could both read and write Telugu perhaps written by herself), though it seemed odd that in Batavia the plant should have had an Indian name. Subbu Subramanya, however, suggests a different reading of the Telugu as ‘champaka shalaka’ meaning ‘stalked champak’, which has nothing to do with ‘milk flower’. Perhaps ‘milk flower’ was a translation of its name in Batavia, but Lady Gwillim’s Telugu-speaking gardeners, realising its affinity with Magnolia champaca, had made up their own name for it.

© The Linnean Society of London, photographed by Leonie Berwick

Magnolia coco is a shrub of two to four metres, has highly scented flowers and has long been in cultivation in both East and West. According to Flora of China it is native to southern China (Provinces of Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Yunnan and Zhejiang) where it grows in forests at altitudes of 600–900 metres, and also occurs in Taiwan and Vietnam.

Cultivation

Sims’s illustration in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine was made from a plant grown in Lee and Kennedy’s famous Vineyard Nursery, Hammersmith, to which it had been introduced from China by ‘J. Slater of Laytonstone’ in 1793. However, according to William Aiton (Hortus Kewensis, ed 2, 3: 330. 1811), it was first introduced from China in 1786 by Lady Amelia Hume. Daughter of John Egerton, Bishop of Durham, she was granted the rank of an Earl’s daughter in 1805 and was a botanical pupil of J.E. Smith. Her husband was Sir Abraham Hume, a one-time Director of the EIC, and the couple had a famous garden at Wormleybury, Hertfordshire, to which they introduced many plants from China and India (the latter especially through William Roxburgh). Others introductions followed and the specimen drawn for Sims in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine appears to have been based on material imported from China by Thomas Evans, then Chief Clerk of the Treasury Office of East India House. The earliest record of the plant’s cultivation in India is in Roxburgh’s catalogue of the plants in the Calcutta Botanic Garden (Hortus Bengalensis, p 43. 1814), to which it had been introduced from China in 1794 under the name of ‘ye-hup’. There is a specimen cultivated in the Calcutta Garden from China in Francis Buchanan’s herbarium at RBGE collected on 1 December 1814.

Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

It seems worth reproducing the letter from J.P. Rottler to J.E. Smith accompanying Lady Gwillim’s drawing of ‘Gwillimia Indica’

To Doctor J.E. Smith

Norwich

My Dear Sir,

It was in March last year when I had the Pleasure to write to you and to send a Packet of dried Plants, but I am uncertain if both have reached you, as I believe that they were on Board the Prince of Wales which Ship is not arrived in England.

This shall now accompany a small Collection of Plants which I gathered since my stay here as I had not any opportunity to go this year on a Journey. The Collection, I am afraid will not be much interesting and the Plants I met with in my former Journies I have left at Tranquebar. As soon as I am certain of my having been established here as a Missionary in the place of late Mr Gericke I intend to get the Herbarium with me, when I then shall be enabled again to satisfy the more the Wishes of my botanical Friends.

Amongst the Collection I have now the Pleasure to offer you is a Drawing of a Polyandria Plant of which I have also made the inclosed Inscription. The Drawing is done by the amiable Lady after whom I denominated it and whose Love & application to Botany really deserves a place among those, whose names are immortalized in the System, I mean the Lady of the Honorable Sir Henry Gwillim Justice of the supreme Court of Judicature at Madras. A dried specimen of the Plant could not at this time be procured, but I hope to be enabled to do it at a next opportunity. Besides this, Lady Gwillim informed me that she has sent to England a living Plant

[There follows a Linnean plant description in Latin, ending with the locality ‘Madrasdae in horto Armeniano, ex Insulis Indiae Orientalis allata planta’ and a note that Rottler could not find it in Schreber’s eighth edition of Linnaeus’ Genera Plantarum, hence his naming of it as Gwillimia indica].

Plant/ which safely arrived.

In my last I had already acknowledged the Receipt of your favour of the 30th October 1802 when I mentioned also the loss of your parcel referred to in the Postscript and for which I am indeed very sorry. At the same time I thanked you for your kind Remarks on the Plants sent by me and by continuing of which you will much oblige me.

At present I have nothing more to add than the sincerest wishes for your Health & Prosperity. My Brethren the Revd. Doctors John & Caemerer & Dr Klein Physician to the Tranquebar Mission join me in respectful Compliments and I have the Honor to be

My Dear Sir

Vepery near Madras Your most obedient

September 2d 1805 servant

J.P. Rottler

1 Comment

1 Pingback