By Henry Noltie

On my daily constitutional to Wardie Bay the ivy-leaved toadflax, Cymbalaria muralis, is currently making a fine display in the lime mortar of the sandstone walls on the eastern side of Granton Road. The plant is not native to Britain, but is classed as an introduction of long standing, an archaeophyte.

The first author to describe it as a British plant was John Parkinson, in his 1640 Theatrum Botanicum. By this time it was already naturalised in ‘divers places of our Land’, including upon ‘thatched houses in the North parts … [especially] Lancashire’, having first been known in gardens around Hatfield, Hertfordshire. One wonders if it might first have been brought from Europe by John Tradescant the Elder, who laid out the gardens of Hatfield House for the Earl of Salisbury in the early seventeenth century. Parkinson’s description of the habit of what he called ‘the Italian Gondelo, or Ivie like leaf’, cannot be bettered:

this small herb creepeth on the ground with slender threddy branches all about,

taking hold on walls or any thing it meeteth,

by small fibrous rootes,

which it shooteth out at the joynts as it runneth.

It was a favourite plant of John Ruskin, who was something of an iconoclast when it came to the naming of plants. He objected to many Linnaean names on grounds of etymology, linguistic correctness, or decency, and his preferred names for what was then officially Linaria cymbalaria relate to his two favourite cities, Venice and Oxford. In the former it was known as L’Erba della Madonna; his ‘Oxford ivy’ was probably an invention of his own, and typically contrary.

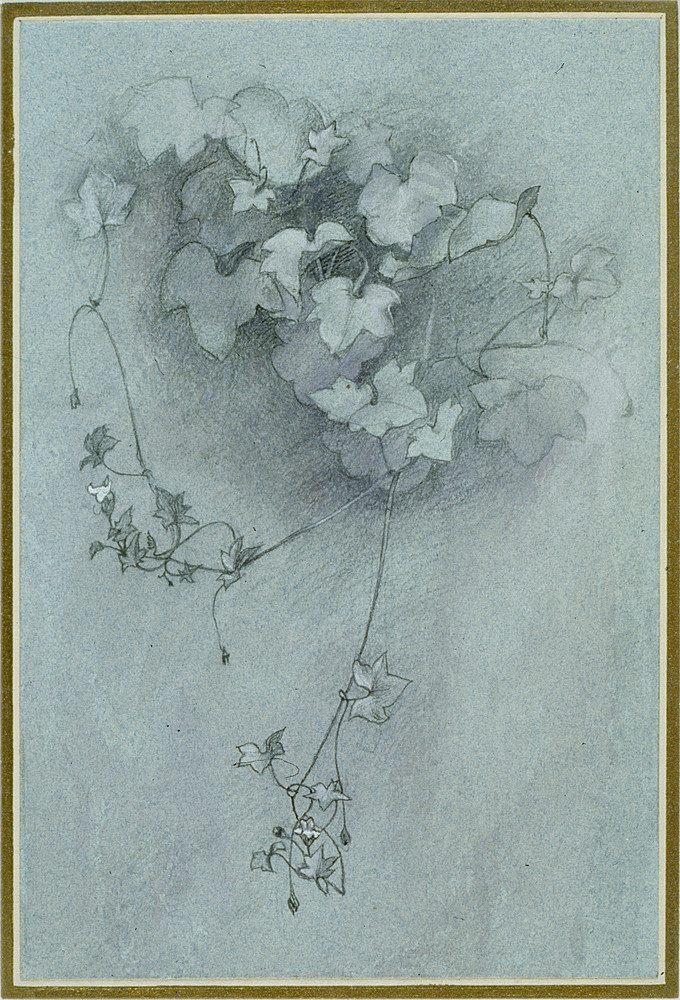

One day in Venice, ‘in a nook behind one of the shafts of the destroyed cloister of San Zaccaria’, Ruskin, took a sheet of blue paper and made a delightful monochrome drawing of the plant in wash, pen and graphite. It has the intensity of one of Leonardo’s plant studies. In 1874 he placed this, along with photographs, prints and other drawings (original works and copies), in one of his specially designed cases (the one titled ‘Introductory subjects and exercises in flower drawing’), as teaching material for the benefit of students of his Oxford drawing school. The school was then based in the Ashmolean Museum, to which the collections, including these ‘Educational Series’, were later transferred.

As there is a connection with RBGE it is worth mentioning another of the groups of drawings in this collection. These, the originals of seven of the illustrations in Peter William Watson’s Dendrologia Britannica (1823–5), were given to Ruskin by a pupil and included as drawings ‘in the old English manner’ . Of these three each are by Mrs J. Travis and J. Hart, and one by Edward Dalton Smith, but the majority of the illustrations for the book, some 156 drawings, have ended up at RBGE at a date and by means unknown.

In the ninth chapter, ‘Of finish’, of the third volume of Modern Painters, published in 1867, Ruskin wrote of ‘how [Giovanni] Bellini fills the rents of his ruined walls with the most exquisite clusters of the erba della Madonna’. Having looked at the large number of examples of one of Bellini’s favourite subjects, his exquisite paintings of the Madonna and Child, available online I have been unable to find one that shows her plant in any of the architectural surrounds. It is, however, clearly depicted in portraits of two altogether more austere male saints.

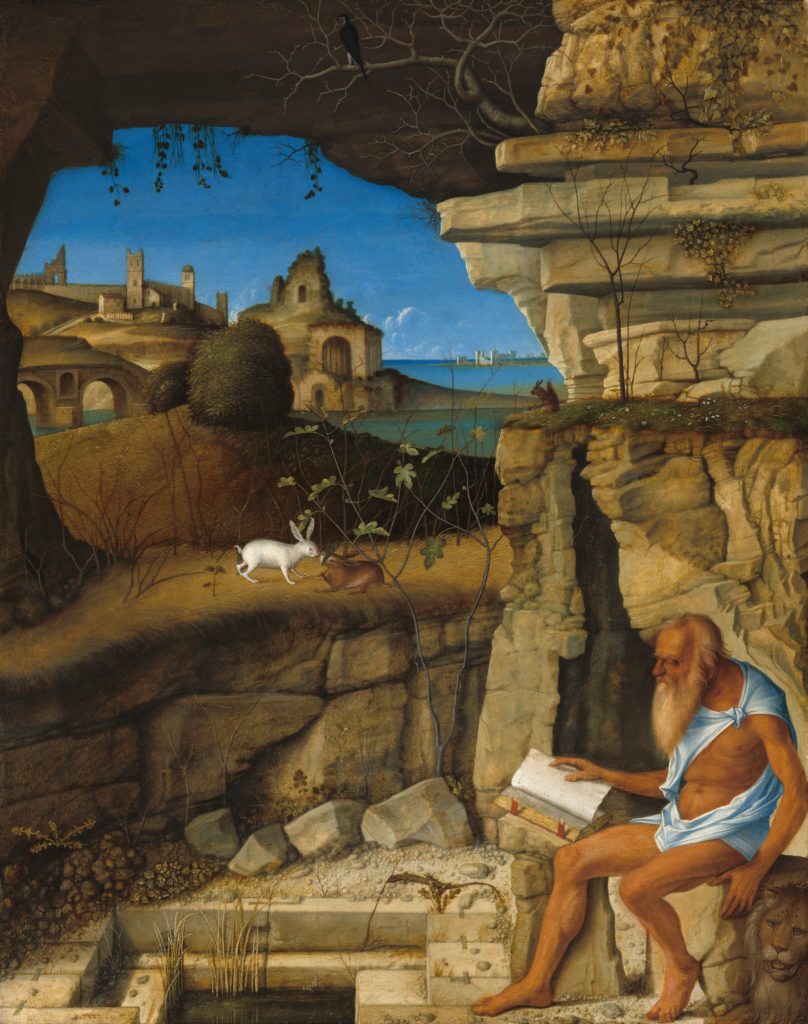

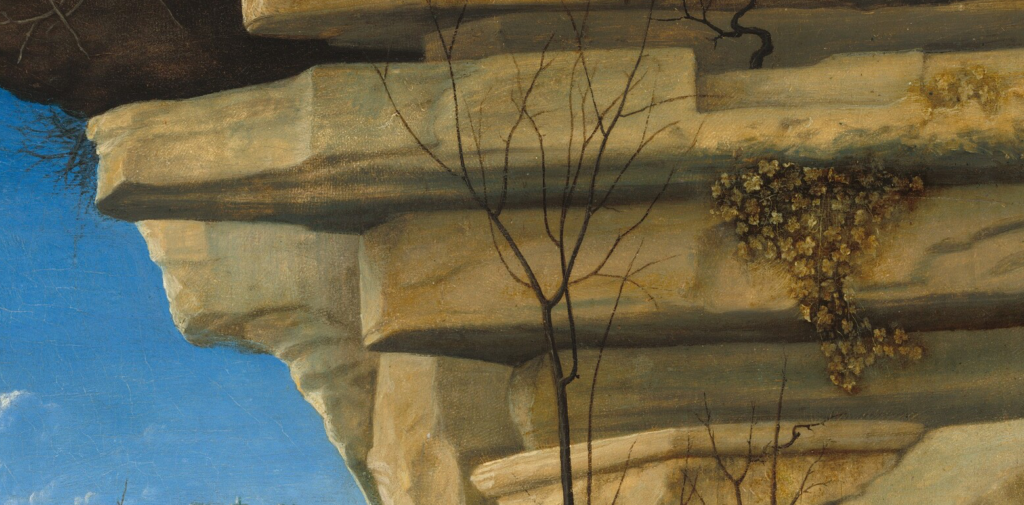

In ‘St Jerome Reading’ of 1505 in the National Gallery of Art in Washington – a healthy clump of the plant can be seen on the cliff above the saint’s head, to the right of a rather sinister, skeletal tree; the Saint, it should be noted, is dressed in a garment that appears to be a prototype of a mankini in fetching sky-blue. In the ‘Ecstasy of St Francis’ of c 1480 in the Frick Collection (in which the Saint is conventionally garbed), some extremely delicate stolons of Cymbalaria dangle from the cliff at the top right hand corner.

In Granton Road the common form is the usual one, rich in a purple pigment (presumably an anthocyanin) that tinges the underside of the leaves and stems, and suffuses the flowers. But also growing here is a form that lacks the pigment, so that the leaves are a yellowish-green and the flowers white, but for twin yellow spots on the palate at the mouth of the corolla.

This is probably the cultivar Cymbalaria muralis ‘Nana Alba’ but, in Ruskinian spirit, I would like to propose a more picturesque name for what is a very attractive plant, and one appropriate for a northern city – even if the regularity of its New-Town architecture failed to meet with Ruskinian approval:

L’Erba della Madonna della Neve.

Post Script

My friend Ian Rolfe has pointed out that the first introduction of Cymbalaria muralis to Britain was, in fact, by William Coys (c 1560–1627), to his garden at Stubbers, Essex, in 1616/7. Perhaps Coys supplied the plant to Hatfield, or perhaps it had already spread there naturally, or by human means, by the time of Parkinson’s record. Coys was a friend of John Goodyer (as in Goodyera) and Matthias de L’Obel (of the Lobelia), and was also the first to flower Yucca gloriosa.