By Henry Noltie

A melancholy arboricultural event took place in the Doune Terrace garden on 26 April 2021: the felling of a stately wych elm (Ulmus glabra). The garden group of the Committee of Lord Moray’s Feuars had done everything it could to prevent, or at least to delay, this murderous act. Only last year it had commissioned a tomographic survey, which found the base of the trunk to be severely compromised, and spent a large sum for tree surgeons to lighten the load of its crown. This was to no avail and by this Spring, though the tree was not suffering from Dutch Elm Disease, the rot at the base had progressed alarmingly. The decision was taken to act quickly as, had the tree fallen in a storm, it would have caused major damage to adjacent buildings. The tree had yet to come into full leaf, but was in the first of its two vernal flushes, its branchlets lime green necklaces from clusters of unripe, winged fruit (samaras).

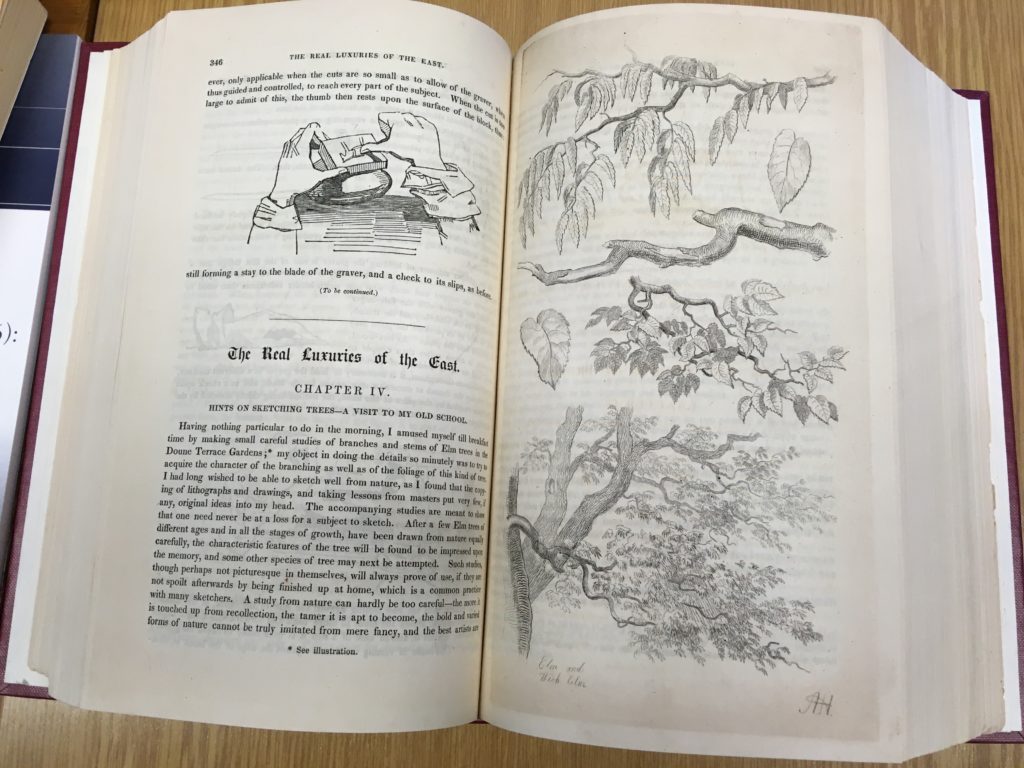

The tree was beloved of local residents, but for me it had an additional resonance. It was the last remaining elm in the Doune Terrace garden, of which there had once been more, and of more than one species. This I knew from an unlikely source – an article and illustration in the Indian Journal of Arts, Sciences and Manufactures, published in distant Madras in 1857. The journal, of which few copies survive, was edited, illustrated, and almost entirely written, by the East India Company surgeon Dr Alexander Hunter (1816–1890), whose father Richard had in 1835 purchased No 1 Doune Terrace, the house directly opposite the fated tree. In the journal, under the nom de plume of Arthur Hope, Hunter wrote a thinly disguised autobiography entitled ‘The Real Luxuries of the East’. In Chapter 4 he described making careful studies of the branches and stems of the elms in the Doune Terrace Gardens one morning as a pre-breakfast recreation:

I had long wished to be able to sketch well from nature, as I find that the copying of lithographs and drawings, and taking lessons from masters put very few, if any, original ideas into my head.

The results were reproduced in the journal as an etching, which depicts two species – a wych elm, and what is probably a variety or hybrid of the small-leaved elm, Ulmus minor. No date for the matutinal incident is given, but it was probably in 1842, during a hiatus when the young artist had temporarily returned to Edinburgh after a brief and abortive attempt to launch his Indian career in Calcutta, and the following year when he successfully did so in Madras.

Hunter’s father Richard and his uncle James had both been in Calcutta as ‘writers’. James had returned to Scotland on inheriting the estate of Thurston, East Lothian, where he continued his father’s work as an improving laird; he also had a town house at No 10 Moray Place. Richard remained in Bengal as a civil servant before setting up a merchant and agency business with a partner called MacGregor. Alexander was born in Chittagong in 1816 and was sent home, presumably to the care of his uncle, for schooling. In 1824, with his cousin Richard, he was in the first year’s intake at the brand new Edinburgh Academy. Alexander’s interests embraced natural science and art – both fine and applied. In 1831, with a view to returning to India as a Company Surgeon, he matriculated at Edinburgh University, from which he graduated MD in 1837.

As described in the autobiography he also studied art in Edinburgh – at the Trustees Academy, at a ‘Young Artists and Life Academy’ in Howe Street, with Montague Stanley (for painting), and he later continued his studies in Paris. He accompanied Horatio McCulloch on sketching trips and studied prints in the Princes Street shop of Alexander Hill (brother of the photographic pioneer David Octavius). These prints influenced his own etching style, which he learned by copying Old Masters including Canaletto and Rembrandt. He acquired a taste for field excursions, an Edinburgh University tradition as continued by his professors of botany and geology, Robert Graham and Robert Jameson and on one of these was George Wallich whose father was Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanic Garden.

In the meantime his parents had returned to Edinburgh, where his father threw himself into the rich cultural and civic life. Richard Hunter’s interests were similar to those of his son and he joined the Caledonian Horticultural Society and the Society for the Encouragement of Useful Arts for Scotland. In 1840 Hunter senior also became a Town Councillor for Ward V and in August 1842 recommended that Dwarkanath Tagore, on the first of his two visits to Britain, be given the Freedom of the City. As thanks for this Tagore sent a set of ragamala paintings by an Indian artist to accompany a copy of the musical treatise the Sangeeta Sastra, which Hunter arranged to be presented to the University, where the paintings remain as one of the treasures of the library.

As already noted Alexander’s start in India was interrupted, but in his first brief period in Calcutta he had showed that he intended to continue with his artistic practice. While there he published, as lithographs, a series of genre studies of local life perhaps, as with ones later made in Madras, influenced by Scottish artists such as Walter Geikie. It was on his return to Calcutta in 1843 that Hunter married Jane Mary Patton, daughter of a Fife family also with strong Indian and artistic interests. The couple immediately headed south to Alexander’s medical appointment in Madras, which would remain their base for the next three decades.

While Hunter’s official duties were as a Company surgeon, with civilian and army duties, his passion for art remained and in 1850 he established the Madras School of Art, effectively the first in India, followed the next year by one for Industrial Art. These were philanthropic efforts, funded out of his own pocket, based on experiments made with getting prisoners to make pottery and bricks while he had medical charge of a jail. He put his practical knowledge of geology and botany to use in finding sources of clay and of soda (made from burning plants such as Salicornia); he also took groups of students on field trips like those he had attended in Edinburgh. It is worth noting that the establishment of this early Indian art school predates the better known efforts emanating from London, and can be hailed as an extension of the Scottish Enlightenment and the principles of the Trustees Academy. In fact the Madras Government fairly soon took over the funding of the school and sought links with South Kensington, which despatched a teacher.

Hunter’s motivation was to train Indian and Anglo-Indian boys in practical art in order to get better jobs, as draftsmen with the Madras Government, or with local firms that made furniture and silver. By 1871 when Hunter left India he had taught ‘upwards of two thousand young men, all of whom had found ready employment’. He also embraced the new technology of photography and in October 1856 Linnaeus Tripe was employed by the Government to record archaeological sites and to teach at the School of Art. Hunter believed in local sources of inspiration, based on drawing from nature – including Indian architecture and local flora, from which designs could be abstracted. In this context it is of interest to note his comments on sketching in the Doune Terrace gardens, of which Ruskin would certainly have approved:

A study from nature can hardly be too careful – the more it is touched up from recollection, the tamer it is apt to become, the bold and varied forms of nature cannot be truly imitated from mere fancy.

The tree felled was the last of the Doune Terrace elms, the small-leaved ones having presumably succumbed to Dutch Elm Disease long ago. The base of the trunk, however, was too rotten to be able to establish the age of the tree. When the trunk is sectioned higher up it might be possible to count its rings, but even if it isn’t quite 180 years old, it must be the progeny of one that was there in Hunter’s day and therefore have been a direct link. What remains are Hunter’s etching, some souvenir branches that the tree surgeon kindly removed for me, and six seedlings rescued from the adjacent gutter. These, I trust, might live long enough to weather the tail end of the present epidemic, and mature in due course to adorn the garden as a memorial to the fascinating character of Alexander Hunter.