One aspect of the Sibbald funded verification project I’m involved with at Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh is the identification of plants that are currently growing in the garden without a species name.

One of these plants was a 1924 collection of Quercus collected by G.H. Cave in Sikkim, who was the director of the Llyod Botanic Garden in Darjeeling. After 92 years, as my colleague Robert Unwin said when he pointed out the tree, “its about time it got a name.”

At the first inspection of the tree, on Monday, there were no obvious flowers or fruits and what was most striking was that the leaves were not lobed or serrated as Oaks so often are.

A quick look at the Flora of Bhutan account for Quercus and related genera found in Sikkim keyed out to the genus Lithocarpus because of the entire margin to the leaf, but flower and fruit would be needed to successfully get a species ID for tree. After going back on Tuesday morning with a pair of binoculars to scan the crown, a request was put to our arboriculture team to climb the tree so they could collect the male inflorescence and any fruit that were up there.

On Friday morning, Will Hinchliffe one of our tree climbers shimmied up the tree and collected some male flowers spikes and immature acorns. A trip to the herbarium with the flowering and immature fruiting material quickly resulted in an identification of Lithocarpus elegans.

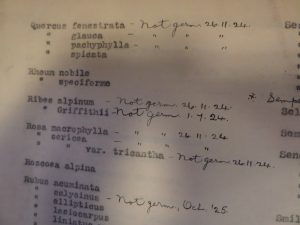

To round off the process and to see if we could add anything to the scant accession record we looked in the 1924 accession book held in the archive. In January of 1924 Cave send RBGE seed of 4 species Quercus, three failed to germinate and the only one that did was Quercus spicatus. Which turns out to be an old name and illigitimate name for Lithocarpus elegans.

It turns out to be a rare tree in cultivation, the BGCI search only yielded 4 other botanic garden collections in the world that list it as growing. What is even more astonishing is that Lithocarpus elegans is found at relatively low altitudes (maximum of about 2000m) in warm temperate and sub-tropical forests of the Himalaya, and by no stretch of the imagination can Edinburgh’s climate be described as either. The secret to its persistence and the reason that it probably went without a name for so long is that its growing in a sheltered unassuming spot in the back of the woodland garden.

The whole process nearly used the full spectrum of the Botanics’ institutional knowledge and expertise: the arboricultural abilities in the Horticulture division safely collected the plant material for identification, plant records and the archive highlighted the history and provenance of the plant and then the library and herbarium collections helped identify and ultimately give the tree a name.

It has also resulted in the odd situation where despite the tree being grown for the past 92 years we have just added a “new” preciously uncultivated species to the living collection.

The botanical wheels turn slowly, but it really is worth it