In March 2020, RBGE was due to host ‘Closing the Loop’ in partnership with Applied Arts Scotland – a workshop for makers exploring environmentally sustainable approaches to materials and making, to complement the Think Plastic exhibition in the John Hope Gateway. However, the temporary closure of the Garden, due to COVID-19, made the workshop hosts seek a different way to hold this workshop. Luckily, they came up with a creative solution: to experiment with a discursive workshop in the virtual realm, enabling participants to ‘travel’ from all over Scotland to take part in this workshop, and prevent location from becoming a barrier.

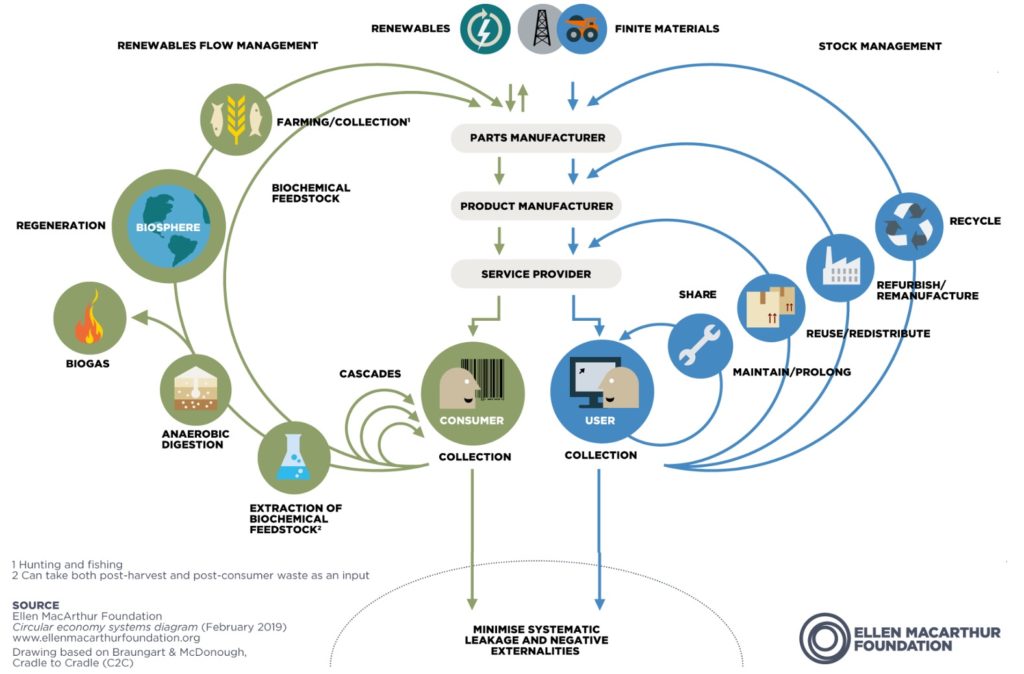

The title of the workshop ‘Closing the Loop’ drew on the concept of circular economies, as described by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. According to the Foundation’s website, circular economies aim to look ‘beyond the current take-make-waste extractive industrial model’, and it offers an alternative framework based on three principles:

- ‘Design our waste and pollution’

- ‘Keep products and materials in use’

- ‘Regenerate natural systems’

The diagram below, from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, shows their vision of circular economies, and the right-hand blue side was the most relevant to the makers attending the workshop, offering prompts for considering how to close the loop in their practice and avoid leakage of energy, materials and resources outside their loop.

Hosting the workshop from her base in Edinburgh, Fiona Pilgrim led participants through an introduction to one another and some of the relevant ideas of the Think Plastic exhibition. There was a moment to reflect on how makers might consider the lifecycle of materials and products they use and produce, taking into account five key stages: sourcing, manufacturing, transporting, using and recovering. This led neatly onto exhibitors and makers Carol Sinclair and Lorna Fraser offering a virtual tour through Think Plastic, pausing to speak about their own works within this.

Carol, who is also the Chair of Applied Arts Scotland, spoke about her mobile Tipping Point, and how when making this she had a desire to use as many reclaimed components as possible – recovering materials, as discussed in the five key stages of an object’s lifecycle. Here she recovered: fishing tackle for the structure of the mobile; plastic milk bottles for the clouds; and recycled filament to use in the 3D pen when making the sun and moon.

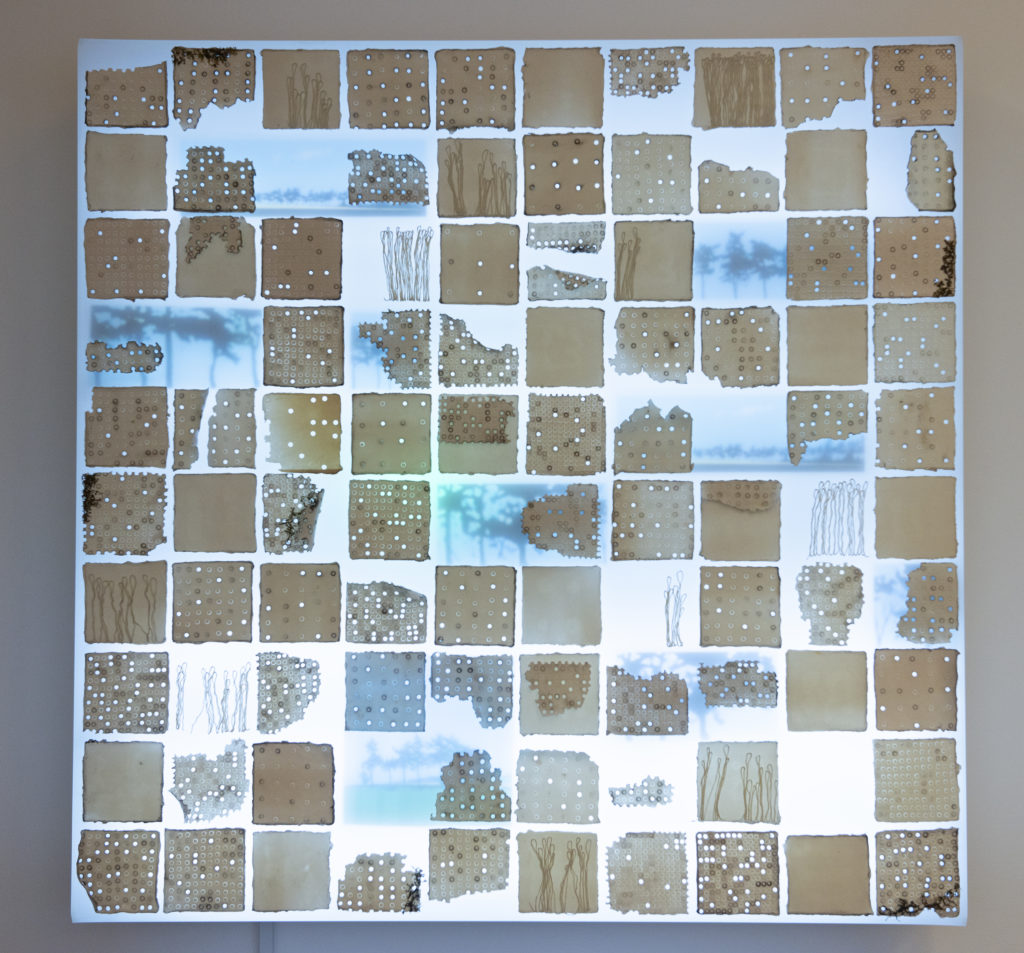

Carol then moved onto discussing Memory Bank, her mixed media work mounted onto a lightbox, and brought up an interesting revelation she had when considering both the ‘recovering’ and ‘using’ stage of this work’s lifecycle. Through new additions to the work, of forms made using recycled fridge plastic filament in a 3D pen, and tiles made using an innovatively conceived material (studio waste in the form of clay dust, combined with PLA plastic), Carol was recovering material from elsewhere in this stage of her production. As a maker who normally works in porcelain, the lightness of the new clay dust/plastic composite material employed in the delicate tiles of Memory Bank enabled her to extend the life of this work. Memory Bank now has less cumbersome and more easily transportable components, offering it a possibility of continued use past its display as a part of Think Plastic, and possibly onto employment in future workshops. Interestingly, through using an often-demonised material – plastic – in considered and precious ways, it empowered Carol to broaden the lifecycle of her materials, and, in turn, find ways to try and close the loop.

RBGE’s Lorna Fraser – an artist, who also works in the Herbarium – normally hand-builds porcelain works inspired by the botanical world. However, here she spoke about how these skills and interests transferred over to using plastic. In Parasol Fungi, for example, she explained how through using recycled water bottles in a thoughtful way – to create delicate Parasol Fungi structures – she was adding value. She wasn’t only recovering materials, but also transforming them to a point where they become precious, valued objects (e.g. for people to buy and have on display in their homes). Therefore, like Carol, she was also extending their ‘use’ period.

Lorna also discussed her work Time to look in the mirror – a piece made from combining the single-use saline syringes used whilst caring for her partner in hospital, with porcelain works that she was yet to rehome or find purpose for. Through the lens of this work, she proffered that not all single-use plastic is inherently ‘bad’. In fact, some of it is necessary, and for these objects we may not always be able to close the loop, but we can admire the benefit they offer. This notion of value and cost was something that the group then paused to examine, with one participant underlining how when we talk about the price of a material (e.g. disposable water bottles being cheap), we often neglect to consider non-monetary costs, in particular environmental costs. Perhaps, if environmental costs were included as monetary, we might think twice before buying non-essential, single-use items.

After a restorative cuppa break for all, we moved on to hear from Fiona about some key ideas and frameworks to consider when thinking about closing the loop. The ReSOLVE framework offered an interesting starting point for further conversation:

Regenerate – shift to renewable energy and materials

Share – assets, reuse/second-hand

Optimise – efficiency in production and supply

Loop – remanufacture, recycle

Virtualise – dematerialise products and experiences

Exchange – old with renewables, business model

This prompted fascinating debate on the ‘virtualise’ tenet, with one participant emphasising that dematerialising and digitising often has a big carbon footprint in and of itself. Referring to BBC Three’s documentary, Dirty Streaming: The Internet’s Big Secret, we talked about how servers hosting so-called ‘dematerialised’ and digitised products and experiences have to exist somewhere, energy has to power the servers, and devices have to be produced and poweredto access the content. So, it seems that ‘dematerialisation’ is actually pretty material heavy.

However, this revelation was deemed far from disheartening by workshop participants, as part of attempting to close the loop is exploring the complexity of methods for doing so. Participants added that platforms such as this workshop offer support to makers in acknowledging these complexities, whilst highlighting that it is important to focus on measurable, achievable and imaginative changes that help to close the loop in your own practice.

Think Plastic is open daily in the John Hope Gateway, from 10am-4:45pm Wednesday 12th August 2020 – Sunday 1st November 2020