Kateryna Sydorova, BSc 3 Horticulture with Plantsmanship student writes:

Margaret Gatty – successful children’s author

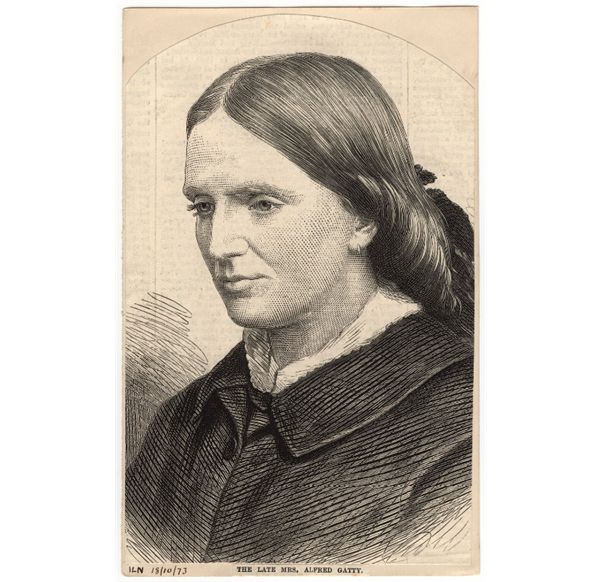

Margaret Gatty was born in 1809 into a family of Mary Frances and the Reverend Alexander John Scott, in Essex. Sadly, her mother died when Margaret was two years old. As children. Margaret and her sister Horatia were encouraged to study languages, painting, and drawing.

After marrying Reverend Alfred Gatty in 1839, Margaret moved to Ecclesfield, Yorkshire, where she lived for the rest of her life. The couple had ten children together, two of them died in infancy.

Between 1855 and 1871, Margaret published children’s stories ‘Parables from nature’ and the successful periodical ‘Aunt Judy’s Magazine.’ Some of her stories were inspired by the natural world: for instance, the phenomenon of Red Snow, caused by single-celled algae. Yet, the main purpose of them was a clear moral lesson for young readers.

Like many people of her time, she had a strong belief in divine creation. And study of the natural world was another way to appreciate God’s creation. Margaret even critiqued Darwin’s evolutionary theory in her ‘Inferior animals’ parable.

Her other two publications, ‘The Book of Sun-Dials’ (1872) and ‘A Book of Emblems, with Interpretations thereof’ (1872), were collections and interpretation of sun-dial mottos and allegories in literature and folktales, respectively.

New calling – algology

After multiple pregnancies, Margaret became increasingly unwell; it is suspected, she suffered from multiple sclerosis and periods of depression. To improve her health, in 1848 Margaret spent seven months at the seaside town of Hastings, in Sussex, where she was introduced to seaweed collecting. It has become her ‘consolation of consolations.’ And in the census of 1851, she was described as ‘Clergyman’s wife. Algologist.’

Margaret began to write to many of the eminent naturalists both in Great Britain and abroad. A very important intellectual friendship and collaboration was developed in correspondence with William Henry Harvey (1811–1866), who is considered ‘the father of modern phycology.’

Gatty’s family could not afford a good microscope and expensive specialist books. Margaret had to borrow books or use proof-plates sent by Harvey. She also asked her publishers to be paid in books by Scottish naturalist, George Johnston for some of her children’s books.

Despite financial difficulties and health problems, Margaret became a nominal assistant to Harvey. She dealt personally with amateur collectors and brought important finds to Harvey’s attention. She also explained how to preserve, identify and describe species to her ‘seaweed pupils.’

Study of British Sea-weeds

In 1857, after a trip to the Isle of Wight, Margaret published a small note on ‘New localities for rare plants and zoophytes’ in The annals and magazine of natural history.

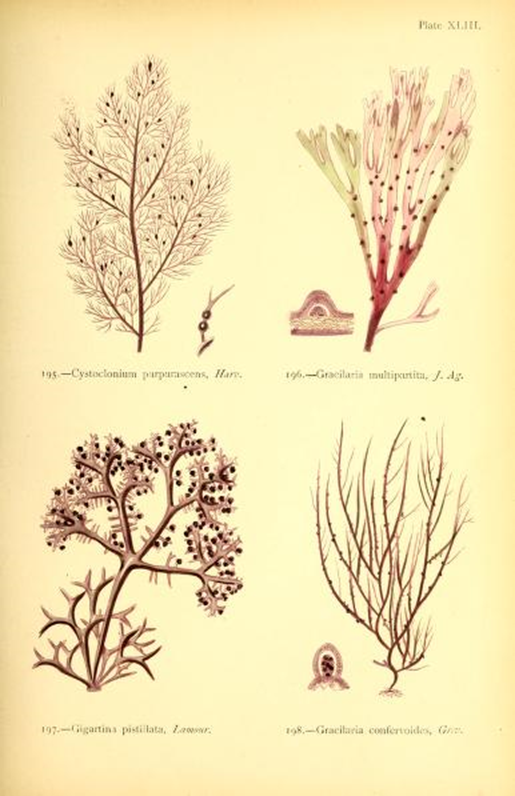

The same year Margaret began to write an educational primer to simplify ‘algological language’, so that amateurs could have ‘real use and comprehension’ of more complicated publications on seaweed. Although Margaret had proofs ready by 1860, this project was never published. Instead her publisher employed Margaret to work on a revised edition of ‘The Atlas of British Seaweeds. Drawn from Professor Harvey’s Phycologia Britannica.’

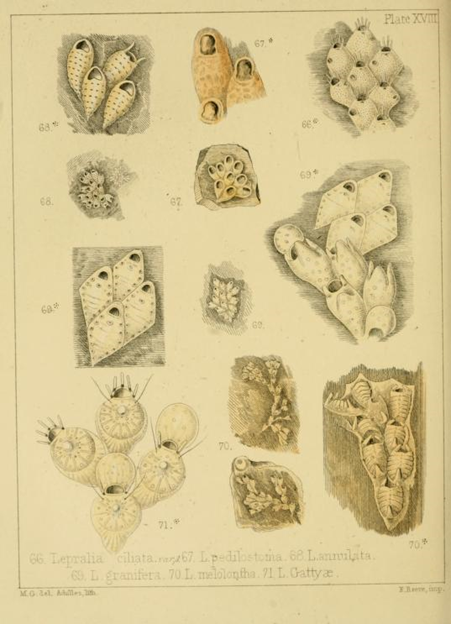

Published in two volumes, under the name of Mrs. Alfred Gatty, ‘British Sea-weeds’ (1863, 1872) became her major publication. It was also aimed at a wider audience and included 86 colour plates, simple species descriptions, recommendations for laying out and arranging specimens in the herbarium, and a key for identification.

In addition, Margaret provided her ‘disciples’ with many practical recommendations for seaweed collecting:

- Study the structure using a magnifying pocket lens, and not rely on the colour to identify the species.

- Female seaweed collectors should forgo ‘conventional appearances’ and adopt ‘a pair of boy’s sporting boots’.

- To prevent cold and destruction of clothes, multiple woolen layers should be worn and petticoats should ‘never come below the ankle.’

- Any ‘rational being’ should leave silks, lace, and jewelry behind.

- Stick can be ’a very desirable appendage’, to balance in on rocks or bring closer sea-weeds floating in the water.

- Collected seaweed can be kept in an ‘Indian-rubber bag’ or glass bottles for more delicate specimens. Equally, a regular lined basket will do.

Margaret Gatty’s seaweed herbarium

With the help of her daughter Horatia, Margaret continued her seaweed studies even when she became increasingly disabled in both arms and legs. She died in Ecclesfield in 1873. A Commemorative plaque and stained-glass window in Ecclesfield Church honours her charitable work for Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London and her achievements as a children’s author.

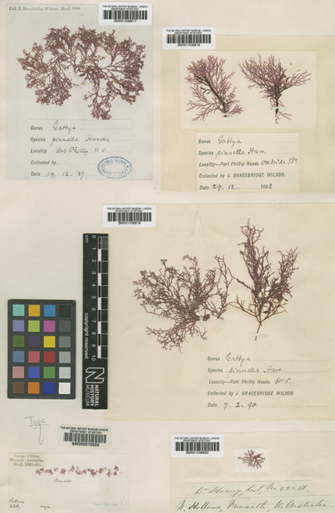

After Margaret’s death her collection of seaweed and marine sponges was donated to Weston Park Museum (Sheffield) and St Andrews University.

From 2013 Dr Heleen Plaisier, from the RBGE, has been working to catalogue Margaret Gatty’s seaweed collection which is kept currently at the St Andrews Botanic Garden. More than 8,825 specimens and 500 plates have been located, half of them still in their original albums. Many of the specimens have records on the date and location of collection, and the name of the collector. This information reveals a wide circle of Margaret’s correspondence and the scope of exchange that was going on between seaweed collectors.

At the time when women were mostly excluded from education and were not allowed to become members of the scientific societies, the hobby of seaweed collecting allowed women to pursue knowledge of the natural world, to contribute to science and even to gain recognition for their expertise. Naturalists, even if they could travel, still relied on contribution from other collectors who reported distribution ranges, provided descriptions and specimens. Among these correspondents were many self-taught female naturalists, who sometimes received an acknowledgement in dedications, introductions or even in the naming of new species.

Fiona

Fiona Bird’s Seaweed in The Kitchen (The Seaweed Sisterhood)