This is an extended version of the talk I gave at the ‘Trailblazers’ online event to mark RBGE’s 350th anniversary on the 15th October 2020.

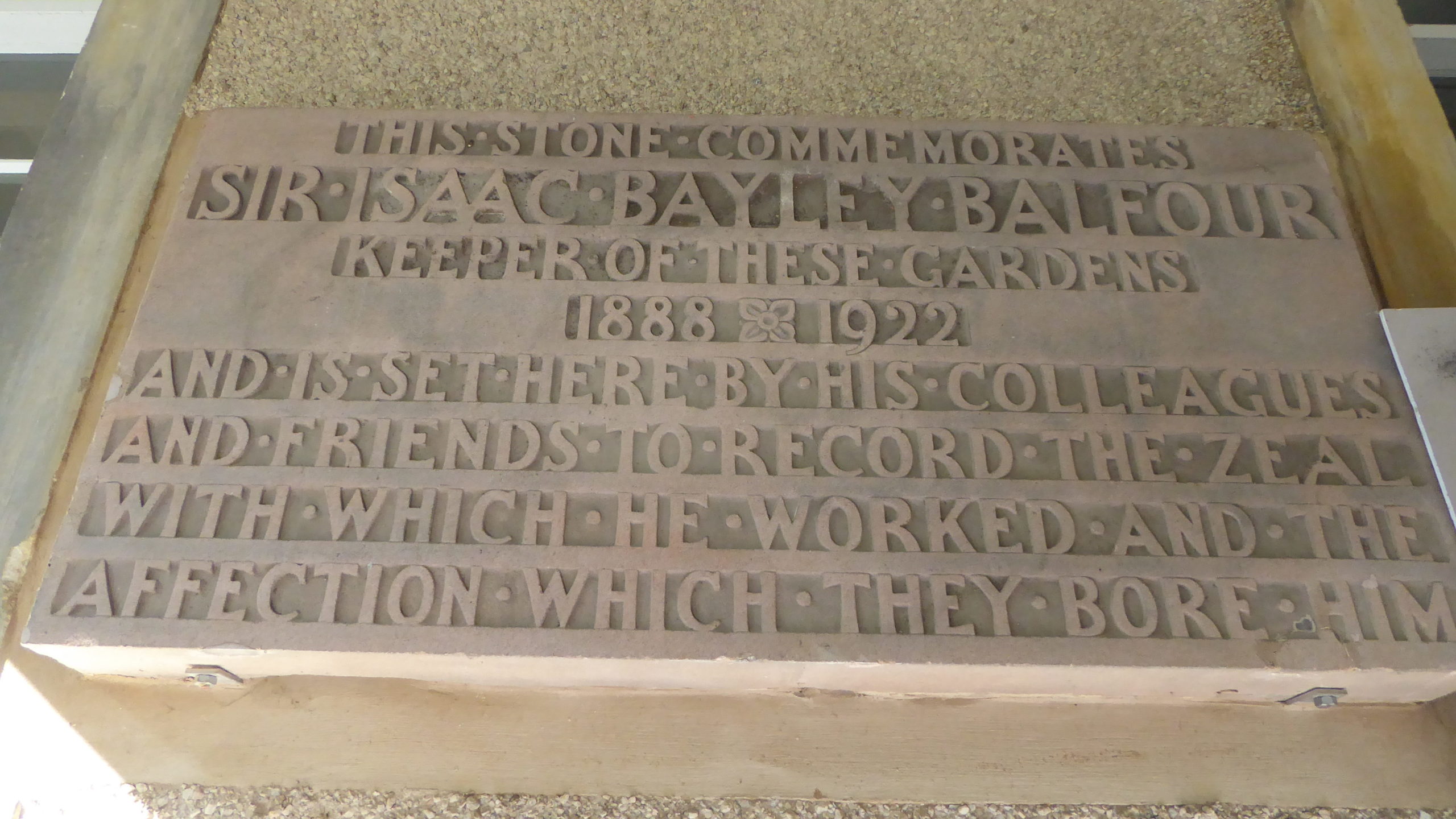

I work in the historical archives at the RBGE, and although we as a Garden celebrated our 350th anniversary last year, the archives don’t date back as far as this – I usually date the foundation of the Archives to Isaac Bayley Balfour’s time as, looking at the records, that’s when you see ledgers and albums starting to appear, proper records of the Garden being kept at the Garden, and efforts being made to search for, locate and record details relating to our history – it was Balfour who, looking to write a historical account, started to collect information to fill gaps in our history – and that’s why I credit him as being the father of the RBGE Archives.

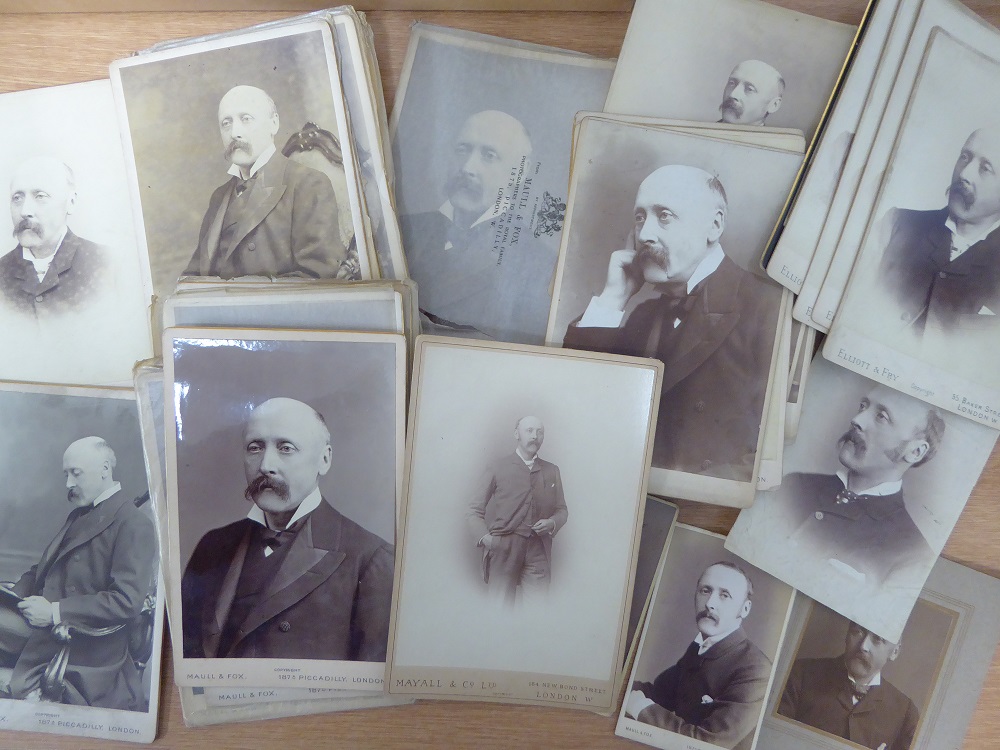

But what do we know about him? And indeed, what do the RBGE archives tell us about him? Apart from the fact he clearly didn’t mind being photographed…

Isaac Bayley Balfour was RBGE Regius Keeper John Hutton Balfour’s third child, his second son, born in March 1853, several years into Hutton Balfour’s tenure as Regius Keeper. Although born at 2 Bellevue Crescent, it was not long before the family moved to 27 Inverleith Row, meaning Isaac was brought up right next door to the Garden – there was actually a door leading from garden of the Balfour’s residence on Inverleith Row directly into the north east corner of the RBGE, and as a child Isaac was apparently a daily visitor, so I think it’s fair to say that the RBGE was integrated right through Isaac Bayley Balfour’s DNA from the beginning of his life.

Not only did Isaac follow his father through the Garden door, he eventually followed him to became Regius Keeper of the Garden in 1888, but prior to this he had:

- Horticultural experience; apparently he spoke regularly with the gardeners at RBGE and in his youth planted many plants at RBGE himself, a fact he was quite proud of!

- Botanical experience; from 1871, at the age of 18 he started taking botany at Edinburgh University and became one of his father’s assistants, doing this job for seven years.

- Medical experience; he was a medical student at Edinburgh University, during which time he worked as a surgical ‘dresser’ in the wards of Joseph Lister between 1875 and 1876.

- Plant collecting experience; in 1874 at the age of 21, after missing out on the chance to be part of the Challenger expedition as they did not need a botanist, he was able instead to go to Rodrigues Island in the Indian Ocean as part of the Transit of Venus expedition- as botanist and geologist he collected plants and samples there; and six years later in 1880 he was able to repeat this experience by going to the island of Socotra, off the coast of Yemen, to collect and study plants there, including the Dragon’s blood tree, shown here below in a illustration possibly drawn by Balfour himself, which produces red sap, hence the name, and introducing many plants new to European science, such as Begonia socotrana, which became the parent plant of many varieties of winter flowering begonia.

- He also had plenty of teaching and administration experience, eventually becoming Professor of Botany at Glasgow University in 1879 and Sherardian Professor of Botany at Oxford in 1884. And this, I think, is where his real strength lay.

It was in 1888, Bayley Balfour finally achieved the position I feel he’d been born for – that of Professor of Botany at the University of Edinburgh and Regius Keeper at RBGE (successfully competing against Patrick Geddes to do so), and he arrived with a considerable reputation for being a dedicated administrator, – and one that had a talent for seeing where improvements could be made and then making them. This may not sound very thrilling, but in the 34 years Balfour was at the helm, the RBGE completely changed and advanced the scope of its operations.

So what did he do?

Firstly, he changed how the Garden was administered and funded – moving it in its entirety away from the Council and the University and having it all under the umbrella of the Crown’s First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings, saving the national identity and Royal status of the Garden instead of it becoming a University asset with a potentially doubtful future.

This was just the start, and Balfour soon began making more changes outside in the Garden; the photographic record (something that also began under Balfour’s reign – not just the regular taking of photographs, but more importantly, the fact they were now being numbered, listed and stored) shows the mass relocation of trees in the 1890s. It was almost unthinkable – the Garden had order beds at the time -plants grown together in their family groups in order to aid the teaching of their taxonomy – and it appears that Balfour wanted to do the same thing with the trees, with different species of the same genera being brought together to form oak lawns, beech lawns, maples grown with maples and limes with limes, the rhododendrons were located on the hill around Inverleith House. I think that was an incredibly bold move.

The glass houses which had become dilapidated were renovated, rebuilt and restructured, with different houses being built for different types of plant – a fernery, bromeliad house, orchid house, etc. increasing the space for plants to be grown under glass.

The Rock Garden was another area Balfour completely transformed… At the start of Isaac’s tenure the Rock Garden looked very artificial, but excellent for teaching purposes as the plants were grown in compartments arranged geographically and by plant families – something Balfour was attempting across the rest of the Garden, but it’s possible that criticism of the appearance of the Rock Garden, most famously by the plantsman, garden writer and plant collector Reginald Farrer, influenced Balfour to try something different here. Farrer, in his book ‘My Rock Garden’ describes three rock garden plans that are not good – he gave them names: the almond pudding scheme was one, the Dog’s grave another, and the last, the one Edinburgh found itself one of the finest examples of; the ‘Devil’s Lapful’ –Farrer describes the plan being

“simplicity itself. You take a hundred or a thousand cartloads of bald square-faced boulders. You next drop them all about absolutely anyhow; and you then plant things amongst them. The chaotic hideousness of the result is something to be remembered with shudders ever after.”

Farrer, ‘My Rock Garden’, 1908, p8

Roland Edgar Cooper was one of the gardeners who worked on the rock garden improvements, and he describes working under Balfour:

“When I arrived at the RBG in 1910 great replenishments with huge slabs of red sandstone and mighty blocks of purple puddingstone or conglomerate were going on [in the rock garden]. On one occasion we laboured to throw up a large mound of earth to IBB’s satisfaction and stood, mostly out of sight, while he considered it with Curator Harrow and foreman Dyker. “No! I think it would look better here,” (a matter of 50 feet away) he said. We sweated to do so in one day, for he was a grand master. Back he came and duly considered it again while we rested on our shovels, well pleased with our good work, and hoping he’d be the same. The verdict this time was: “It doesn’t look well there. It was better before. Put it back. There was a lovely sunset that day.”

ROLAND EDGAr Cooper, ‘Soliloquy’, Journal of the Scottish Rock Garden, 1953, no13, pp222-224

Cooper went on to say that “It was only in later years that I tumbled to what IBB’s conception of a rock garden seemed to be. [and] It was a magnificent one…”

To carry out all this work Balfour needed more staff – more gardeners and labourers, and to do this he established the probationer gardener programme, similar to an introduction of apprenticeships – the establishment of formal training for gardeners and, more controversially, he added a training programme for foresters to this too. The idea was that young men would come to the garden for a period of three years, they would work in the Garden, presumably for a very basic wage, but get a series of lectures and exams in subjects such as horticulture, forestry, propagation, botany, book keeping, surveying, mensuration, etc. They would therefore leave at the end of three years with a greatly enhanced c.v. and better job prospects, and if they did well, they were in good position to be recommended to vacant posts by RBGE. Additionally, if RBGE needed permanent staff, they could cherry pick the best men too, so it was quite an advantageous scheme all round – if you were a man.

In 1897, after a successful experiment at Kew, RBGE were persuaded to take two female candidates onto the probationer gardener programme. The women were Lina Barker and Constance Hay-Currie, and when invited to attend they were asked to wear the uniform that a boy would wear – the Kew ladies can be seen demonstrating something similar above in a photograph from Kew’s Guild collection. Barker was happy to do this, but needed time to buy the outfit. Constance Hay-Currie refused, and came in to work in her skirts. Balfour needed to have words, and we have the notes from the interview in the Archives:

“On the end of November I had an interview, at which the Assistant Head-Gardener was present, with each of the women-gardeners: Barker agreed to conform with the regulations, but pleaded for a little longer time on the ground of expense. Currie – I here quote from my minute of the interview – “maintained her position that nothing would induce her to wear the costume stated. She considered it an advantage to show she was a woman in order to encourage women to take up gardening. Reminded she had never worn the Kew costume and that I had previously told her I should have to insist upon it later, she remarked she regarded what I had said as a joke. Of course Miss Currie’s employment here ceased.”

This is an intriguing dilemma – many today would be able to see where Constance was coming from and agree with her point of view, and it is admirable how strong she was to stick to her guns, but, it could be argued Balfour had good reason to insist on the Kew outfit – the Kew ladies caused such a sensation when they attempted to work in something more feminine, the fuss didn’t die down, nor could they get any work or study done, until they dressed in a more masculine style – or perhaps became more equal in appearance to the male staff? It is understandable why Balfour was keen to adopt this outfit straight away. It could also be argued that if a male member of staff spoke to him that way he’d have been fired too, but Constance Hay Currie does seem to have been treated very harshly by Balfour.

To summarise, one of Balfour’s most enduring legacies was his improvement of our educational output – as well as the horticulturists and foresters, he was, of course, still teaching botany, especially to the medical students of the University of Edinburgh, and also offering classes to the citizens of Edinburgh and beyond on Saturdays.

One of these medical students, Dr Bell Nicoll recalls how intimidating Balfour was:

“Sir Isaac Bayley Balfour was the presiding genius over this Mecca [referring to RBGE] and he was a man whom we feared greatly. Sir Isaac was a character and only the very great can afford to be ‘characters’. He invariably wore a broad-brimmed straw hat when outside. The hat was of a bygone vintage and looked like some relic that Queen Elizabeth [the 1st] had cast aside”

Dr Bell Nicoll told of a story passed amongst the students as a warning:

“In the years before the first world war it was the custom for the Professor of Botany to take his class out for a botanical excursion on Saturday mornings. One day he was standing beside a hillside pond on the Pentland hills near Edinburgh demonstrating the peculiarities of algae. The class were crowding round him on the landward side, when one youth, with more brawn than brains, gave the class a shove. The professor lost his balance and was pushed into the water.”

J.T. Bell Nicoll, ‘The Span of Time: the Autobiography of a Doctor’, Hodder & Stoughton, 1952, p.70

The moral of the story was that that particular student never passed his professional exams. Bell Nicoll then goes on to say that that student joined the army and on the outbreak of war was killed in France. Now this is purely a hunch on my part, but I have spent some time researching the men on our war memorial, and if this man is who I think he might be, again – pure speculation, Balfour went on to name a plant after him in order to hold his name in memory – is it possible the man was David Hume? And the plant named after him, Roscoea humeana, which I think if so, shows it’s possible the story became exaggerated, perhaps in order to induce students to behave properly on field trips?

But this brings us on to one of the most significant events that happened during Bayley Balfour’s tenure, the First World War, a time when of Balfour’s 88 male members of staff, 73 enlisted, 56 of these having done so by the end of September 1914. Balfour wrote in a letter to Reginald Farrer in February 1915:

“Fortunately, the loyalty and fine spirit of all who are left carried us over our most critical period, but now I have to carry on as best as I can with such old men of non-military age or younger men unfit as we can secure from the ranks of the unemployed. It makes gardening very difficult and I fear – nay I know – that our collections are suffering sadly. However nothing matters here but the war. A temporary set-back to our gardening efforts is nothing to the saving of our race from suppression – for that is the inwardness of the whole business.”

I.B.Balfour to R.Farrer, 6 Feb 1915 (RJF/1/1/1/16)

Of course it was a horrendous time for the men that left, 20 of them losing their lives, it was also a difficult and onerous task to keep the garden functioning during this time with such reduced staff levels, and worst of all for Balfour, his only son, named after him, but called Bay by the family was himself killed in Gallipoli in June of 1915.

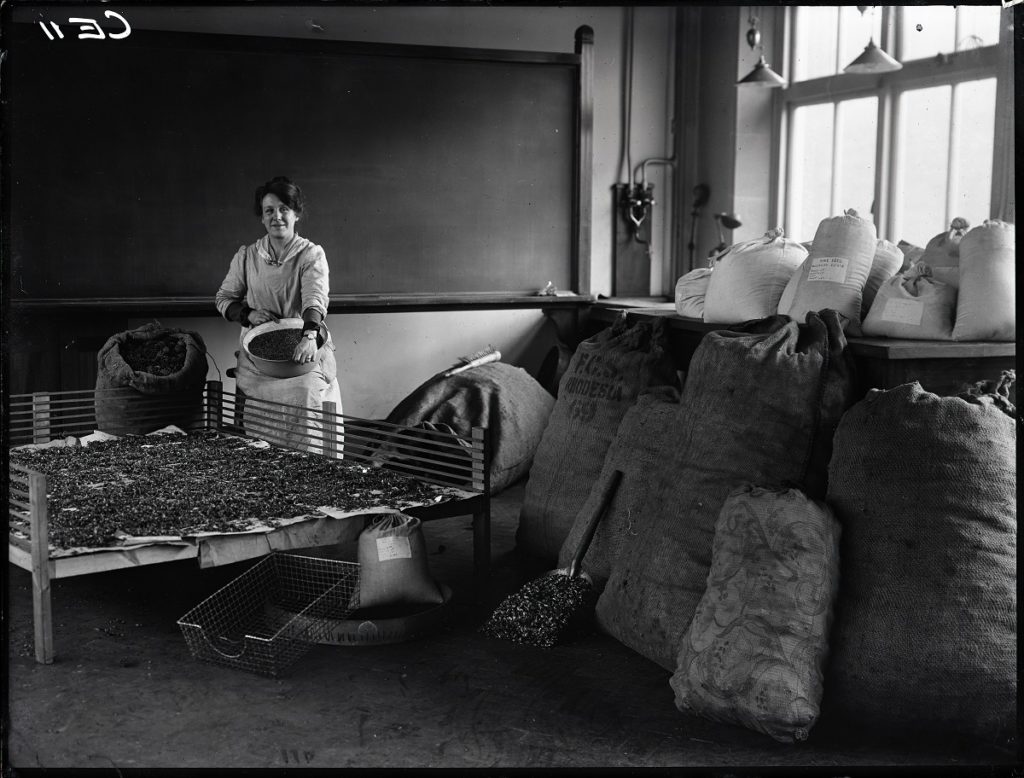

Balfour was awarded a Knighthood in the civilian war honours list in 1920, for ‘services in connection with the War’ and it seems that to earn this, not only did he keep the Garden going, but he also contributed to the Timber Supply Dept – Britain’s effort to secure and maintain vital supplies of timber during the war, and to quickly repopulate forests after the war, and this photo above possibly shows part of that effort, a lady called Miss McQueen working on drying and harvesting seed from pine cones in one of RBGE’s teaching rooms in 1919, and Balfour was also instrumental to the effort to collect supplies of correctly identified sphagnum moss that was effectively and successfully used as anti-bacterial wound dressings for soldiers injured on the western front. Balfour worked on the experimental and scientific side of the operation – assisting in the work of identifying the best type of moss to use – what makes the best dressing, how best to dry it – what works, what doesn’t. Below is a photo from RBGE’s sphagnum archives, showing moss collecting near Moffat in Dumfries and Galloway.

However, for me, Balfour’s most crucially important and game changing achievement was his partnership, if you will, with the plant collector George Forrest. Balfour was very interested in the flora of China, and when in 1904 he got the chance, he recommended one of his herbarium clerks, George Forrest, to go on a plant hunting expedition to southwest China, becoming the first of seven very successful expeditions for Forrest. As part of the deal, Balfour would get a supply of seeds and herbarium specimens to study and name. Edinburgh became known as, and still is, a centre of excellence for the study of Sino-Himalayan plants, and for its taxonomic work, and Balfour became expert in rhododendron and primula in particular.

To support this, Balfour improved and expanded RBGE’s laboratory facilities, building what we now call the Balfour building on Inverleith Row, but not only that, the seeds sent from China were propagated and grown and the range of plants in the Garden expanded, and it soon became apparent a new and different garden would be needed to grow many of these new plants. Hence, at the time of his retirement in 1922, Balfour was working on the acquisition of a ‘satellite’ or a regional garden as we would call it now. Balfour favoured Benmore near Dunoon, and eventually, in 1929, it was acquired and became RBGE’s first regional garden soon becoming populated with the new rhododendrons arriving from China. It is also the site of one of the most attractive memorials to Bayley Balfour, Puck’s Hut, written about in RBGE’s new book written by Benmore’s David Gray.

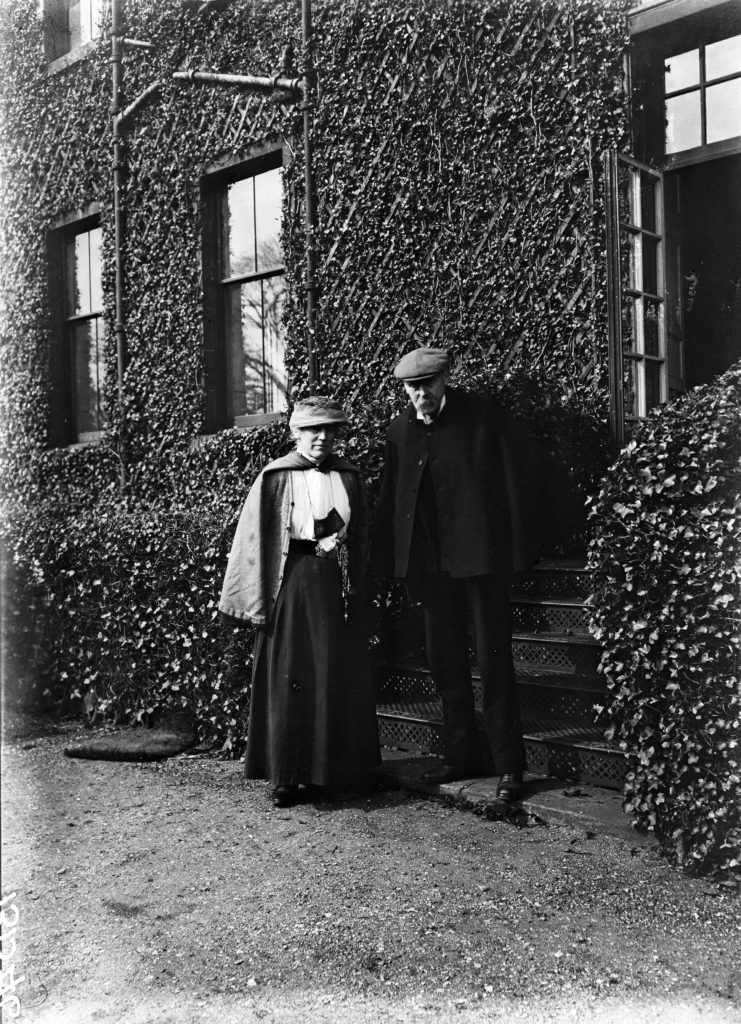

A lot of the letters and descriptions of Balfour show him to be quite an imposing character –intimidating and not to be messed with; witty, but you wouldn’t want to be at the receiving end of that wit – but the overriding impression from his obituaries show him to be knowledgeable, and very generous with that knowledge, and that is certainly how he comes across in the correspondence in the Forrest archive– people came to him time and time again for advice and Forrest and his wife Clem – who had also worked in the Garden under Balfour seemed to look on him as a mentor or father figure, they affectionately referred to him as ‘Ikey’, but I suspect behind his back.

One thing is sure though, Balfour was absolutely dedicated to RBGE– after becoming Regius Keeper, he rarely moved outside the sphere of the Garden – he was based at Inverleith House within the Garden walls and everything he did was for the improvement and advancement of the Garden that had been his life. Ill health however, forced him to retire and leave the garden in 1922. Exhausted, ‘broken’ and eventually bed-ridden, he and his wife relocated to Haslemere in Surrey, so that he could recover, continue his studies and finally produce his long worked on history of the Garden but it was not to be; he died a few months later in November 1922. A memorial was soon erected in the Garden so that everyone who visited us would know Balfour’s name, and I hope you’ll agree that it’s certainly a name worth knowing.