By Henry Noltie

Rituals to mark the unrolling of the seasons have always seemed important, but never more so than as reference points by which to punctuate the longueurs of lockdown. For me a powerful symbol of the vernal renewal of plant growth is to be seen on my regular drives to Dundee, on the roadside at Kinfauns to the east of Perth, with the annual eruption of colonies of the chunky, pale yellow-green inflorescences of Petasites japonicus.

From a distance and in lateral view the short spikes look somewhat pyramidal, but when viewed from above their narrowly tongue-shaped bracts, being spirally arranged, give them more the appearance of multi-armed starfish. The robustness is in fact illusory as the stems are hollow, soft and sappy. The cylindrical capitula are of a dirty white colour and the florets in this, as in other naturalised British populations, are entirely male. The inflorescences are relatively short-lived and in summer are replaced by large, umbrella-like leaves that quickly become untidy and tattered. It was for the leaves that Dioscorides coined the name Petasites, from the Greek name for a broad-brimmed hat, petaros.

Every year I stop and perch the car at the edge of the dual carriageway and, as lorries and cars thunder past, leap out and pick three spikes. These I put on my kitchen table in a treasured flower brick by Sarah Walton, salt-glazed and the colour of laterite. Although trips to Dundee have, of late, been somewhat restricted, the removal of my mother to a care home, and eventual permission to visit her (following an on-the-spot Covid test) last Thursday allowed the performance of my ritual as in previous years.

Henry Drummond-Hay and Seggieden

The origin of this population is almost certainly as an escape from the garden of Seggieden (Anglice: valley of the yellow flag-iris). The mansion, long-since demolished, was an elegant, bow-fronted Georgian one that stood on a terrace close to, and overlooking, a noble stretch of the Tay (not far from where Millais painted his ‘Chill October’). In the second half of the nineteenth century it was the seat of the noted ornithologist Colonel Henry Maurice Drummond-Hay (1814–1896). Born Henry Drummond at nearby Megginch, he was the son of Admiral Sir Adam Drummond and his wife Lady Charlotte, a daughter of the 4th Duke of Atholl who was a niece of the botanist Lady Charlotte Murray. In 1859, on his marriage to the heiress Charlotte Richardson Hay, he acquired her property and appended her surname to his own.

Drummond-Hay was a professional soldier in the Black Watch who in retirement commanded the Royal Perthshire Rifles Militia; his passion, however, was for natural history. A founder member of the British Ornithologists’ Union he was possibly the last man to see a living great auk, from a ship off the coast of Newfoundland in 1852. Drummond-Hay was also an outstanding taxidermist and the galleries of Perth Museum, of which he was for many years the honorary Curator, were once filled with his exquisitely prepared mounted bird groups, which I admired as a child, but that were swept away in a lamentable programme of ‘modernisation’.

The Colonel was also a keen botanist for whom in 1886 his friend Francis Buchanan White named a (no-longer recognised) variety of yellow rattle that they found together at 3350 feet on Ben Lawers: the quadruple-barrelled Rhinanthus crista-galli var. drummond-hayii. Of his botanical interests a biographical memoir in The Ibis noted that ‘Few could rival his garden in its show of rare herbaceous plants’. One such rarity must have been the giant butterbur, which can have been introduced only shortly before his death in 1896.

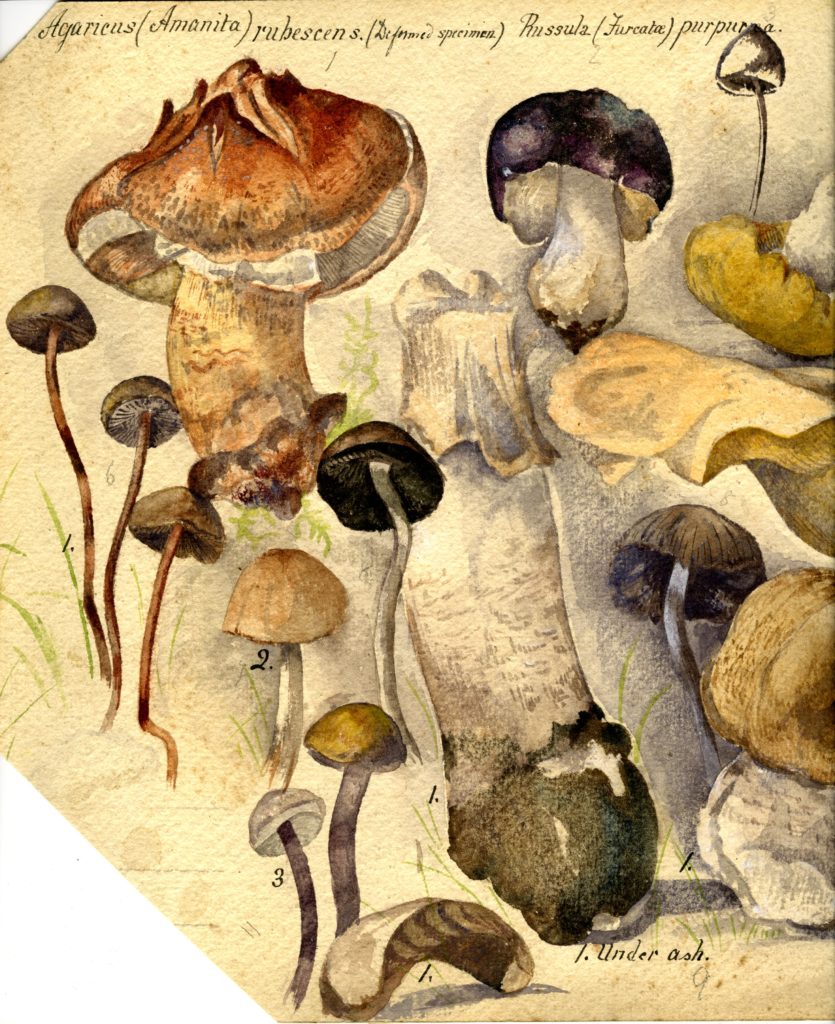

The genes for an interest in natural history were passed on: his eponymous son Henry (1869–1932), who became a tea-planter in Ceylon, is remembered as an herpetologist (commemorated in two snake species); his daughter Constance (1862–1944) painted bold watercolours of fungi, now at RBGE, of which her great aunt Lady Charlotte Murray could have been justly proud.

Ito Keisuke and nature prints

I think that it was in 2001, when fossicking among the Compositae covers in the Kew illustrations collection, that I came across Petasites japonicus in an altogether different form. Whereas most illustrations are flat, or folded at most into two, this one resembled a small pillow of soft tissue that, when unfurled, became a sheet of Chinese paper 170 by 86 centimetres. The image it bore, in an unearthly shade of copper-green, was a nature print of a whole leaf, and parts of two others, of the butterbur; written beside the leaves was a long note in Japanese script. Several years later I drew this marvel to the attention of Jim Kay. In his pre-Harry Potter days Jim worked on illustrations in the Kew library and with Nicholas Hind, the Compositae expert there, he wrote an article on the nature print. They had the note translated, which states that the print belonged to the Japanese botanist Ito Keisuke (1803–1901).

Keisuke was brought up in the tradition of herbalism and Confucianism, but was instructed in Western botany and medicine (including vaccination) by the German botanist Philipp von Siebold while the latter worked as surgeon to the Dutch East India Company on the island of Deshima in Nagasaki harbour to which foreigners were confined. The print was given to Kew’s martinet of a director, William Thistleton Dyer, by Keisuke’s grandson in 1885. The note implies that the image was made at Akita (in northern Honshu) by Ito when he was 80 years old and was printed using the plant’s own sap. Much interesting additional information on the plant is also given in the note: it grows on mountain riversides in the Towada mountains of Aichi Prefecture and in Hokkaido; its local name is fuki; its leaves, taller than a man mounted on a horse, are used as umbrellas; its leaf stalks are eaten boiled, pickled or crystallised in sugar. The plant is still eaten in these ways today, as are the inflorescence buds while still enclosed in their bud scales. Kaisuke also stated that ‘when the plant is exported to a foreign country it will still grow large, but gradually reduces its size and vigorousness due to the different environment’.

Since Hind and Kay wrote their article in 2006 it has emerged that the Kew print might not, in fact, be the work of Ito Keisuke himself, but for further enlightenment on this fascinating question we eagerly await the findings of Michele Rodda of Singapore Botanic Garden, who is currently working on the topic of large-scale nature prints of Petasites japonicus, which he tells me are called akitafukizuri and were made for the adornment of screens and sliding doors in Japanese houses (for some spectacular images of these type 秋田蕗摺 into Google. An image of another Petasites nature print from the collection of Ito Keisuke, in the National Diet Library in Tokyo, can be seen at https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/2543132/5.

The information on the Kew print about the foreign cultivation of the plant suggests that it was already being exported as an horticultural curiosity as early as 1883, though its main introduction to Britain probably came through the Yokohama Nursery Company in the 1890s. It reached Kew only in 1899, from where it was illustrated in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine in 1905. The plant was first described in 1843 by Siebold and Zuccarini (in the genus Nardosmia) and was transferred to Petasites by Maximowicz in 1866. The form in cultivation has been described as subsp. giganteus, though how this differs from the typical one, other than in size, is unclear. The plant occurs in Honshu and Hokkaido, in north-east China and Korea, and on the Kurile Islands and Sakhalin. It appears not to be recorded from Kamchatka, though in habit it resembles the megaherbs for which that peninsula is famous.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for conversations with Michele Rodda and Jim Kay, but much remains to be discovered, or at least made available in English, on the Japanese nature prints of the fuki.

References

Anon., 1908. Colonel H.M. Drummond-Hay in Biographical notices of the original members of the British Ornithologists’ Union. Ibis, ser. IX, vol 2, Jubilee Supplement: 75–7.

Hemsley, W.B. (1905). Petasites japonicus. Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 131: t 8032.

Hind, N. & Kay, J. (2006). A nature print of Petasites japonicus subsp. giganteus. Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 23: 325–41.