Oblong woodsia (Woodsia ilvensis), a small, rare mountain fern, was virtually wiped out in the Moffat Hills by commercial collectors responding to the Victorian craze for ferns – pteridomania – that began in the late 1840s. Botanists collecting for ‘scientific purposes’ added to the pressure on this prized species and today it is one of Britain’s rarest ferns.

This ferns demise was shockingly rapid. The fact that botanists from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh were involved is not as surprising as it may seem. Attitudes were quite different at that time and the idea that the natural world might need to be protected from human impact was unappreciated by most people. Unfortunately, improved access, due to expansion of the railway network, and the fern craze proved to be a terrible combination for oblong woodsia. The fern was stripped from the hillsides in just a few decades of its discovery.

Completion of the Caledonian Railway in 1848 provided easy access to the Moffat Hills from Edinburgh, Glasgow and Carlisle. Moffat had already gained a reputation for health-giving waters, rich in sulphur, that emerged in the hills. These waters were transported to bath houses in the town and the railway provided a boost to this developing tourist trade. In July 1848, the same year that the railway arrived at Beatock (2 miles from Moffat), William Stevens discovered oblong woodsia in the Moffat Hills:

This rare and handsome little fern I found in considerable abundance on very steep, crumbling rocks among the hills dividing the counties of Dumfries and Peebles, in July last; it is growing in dense tufts in the crevices of the rocks, and very luxuriant, many of the fronds measuring nearly six inches in length.

William Stevens (1849), The phytologist 3: 390-393.

It did not take long for hotel owners to spot a new business opportunity in the form of fern collecting. The middle class craze for ferns drove up demand for rare species. This then pushed up prices to a point where commercial collecting became viable. Publicity material aimed at fern tourism even mentioned the ferns and other local flora. Printed albums were available to be filled with specimens.

Following the initial discovery by Stevens in 1848, a further population was found in the Devil’s Beef Tub in 1850. Subsequent finds at Loch Skene, Hart Fell and the head of the Carrifran Burn highlighted the importance of the area for oblong woodsia. It became clear that the Moffat Hills were the British headquarters of this species. So, it is deeply shocking to discover that by 1891 the fern was only known as a single individual in the hills around Moffat.

Within 42 years of being discovered in southern Scotland oblong woodsia was on the brink of local extinction. The relatively accessible corrie known as the Devil’s Beef Tub (possibly a corruption of bathtub due to the mineral springs present, or the place where the Border Reivers of the Johnstone clan – referred to as “devils” by their rivals – kept stolen cattle) had been completely collected out within three to four years of the initial discovery.

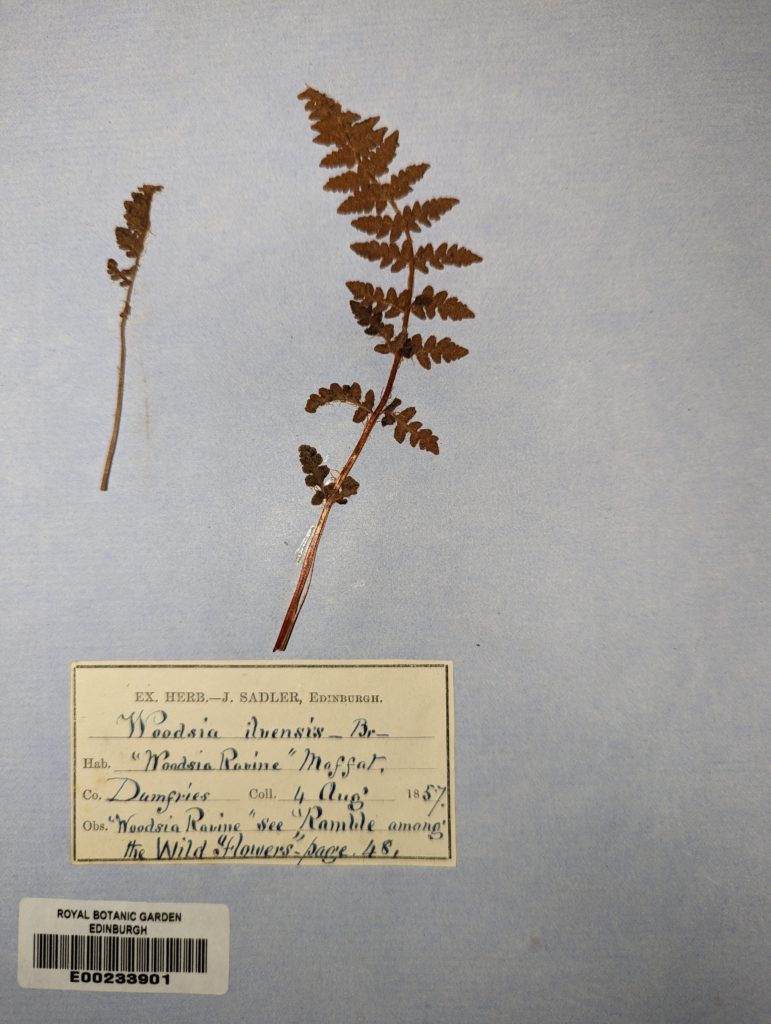

The role of botanists in this rapid decline is clear. Professor John Hutton Balfour, Regius Keeper of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, described collecting oblong woodsia ‘in considerable quantity’ during a botanical excursion he led in July 1856. By 1860 the fern was clearly becoming difficult to find. John Sadler, assistant to Professor Balfour (subsequently promoted to curator of the Garden), described how he almost fell to his death trying to reach an inaccessible clump of oblong woodsia above the Carrifran falls. A few years earlier, in 1857, Sadler wrote an account of a botanical ramble around the Moffat Hills. During an extensive search of what he named the “Woodsia Ravine” (see specimen label above) his party found and collected oblong woodsia. Sadler makes this matter of fact note of the occasion:

The plant does not seem very plentiful where we visited, five small tufts being all we observed, of which we took four, leaving the other as an “egg in the nest”.

John Sadler (1857), narrative of a ramble among the wild flowers on the moffat hills in august 1857 (pages 46-47).

In February 2024 Becca Drew, and others from the Garden’s Scottish Plant Recovery project, visited the Devil’s Beef Tub to assess the suitability of the site for the planting of oblong woodsia. Becca is the Garden’s lead horticulturist for the five non-woody plants included in the project. Before plants can be returned to to the wild it is vital that we are able to find the precise conditions a species needs to thrive – its ecological niche. We also need to know that the pressures which pushed a species to the brink of extinction have been removed. Thankfully, fern collecting is no longer a popular pastime.

As a former site for the species, the Devil’s Beef Tub could still have suitable habitat for oblong woodsia. However, it is a large site and most of it is clearly unsuitable. Finding the right spots takes knowledge of the species and a lot of time spent searching. Becca has benefited from the experience of horticulturists Andy Ensoll and Kate Miller, who joined the site assessment trip. Over many years, Andy and Kate have perfected the art of growing oblong woodsia in cultivation. Propagation from spores and crossing plants from different locations, to increase genetic diversity, has also been successfully achieved. Applying this knowledge of the ferns growing requirements to the hunt for its habitat in the wild is a perfect example of how science and horticulture come together.

Plans are being developed to return cultivated plants to the Devil’s Beef Tub and to sites at Kilchoan and Glencoe on an experimental basis in May 2024. The spread of sites has been designed to include wetter localities in the west of Scotland. The only British site where oblong woodsia is doing well and is increasing is Wasdale Screes in Cumbria, where it grows in a relatively wet climate. Plants will be closely monitored to assess how well they perform in their new homes. These trials are necessary for oblong woodsia as there has been a history of poor success with past plantings. Numbers of individuals have tended to decline over a period of years and almost no sign of a new generation of young plants has been seen. This suggests that the planting has been carried out in places that are not providing quite the right conditions.

The intense collecting of oblong woodsia that took place in the Victorian era means that surviving wild plants are likely to be in the most inaccessible places that may not be representative of where this fern grows best. This is why a more experimental approach is useful and why the trials will be so informative. Also, seeing the fern in places outside Britain, where it is thriving, can help us find the right places to put our precious plants.

The Botanics team is developing restoration plans with a steering group of interested individuals and organisation including National Trust for Scotland (Dan Watson) and the Borders Forest Trust. The slopes around the Carrifran Burn, owned by the Borders Forest Trust, are of particular importance as they held historical populations of oblong woodsia.

The imminent return of oblong woodsia to the Devil’s Beef Tub feels like restitution – giving back something lost or stolen – as much as conservation of a threatened plant. That this beautiful alpine fern may once again be securely established in the Moffat Hills is something to look forward to. I will be reporting back on how the trials develop.

- X @TheBotanics

- X @nature_scot

- X and Facebook @ScotGovNetZero

- Facebook @NatureScot

- #NatureRestorationFund

Acknowledgement: Much of the historical context is drawn from an article by J. Mitchell published in 1980 – Mitchell, J. (1980) Historical notes on Woodsia ilvensis in the Moffat Hills, southern Scotland. The Fern Gazette, 12(2): 65-68.