H.J. Noltie

Introduction

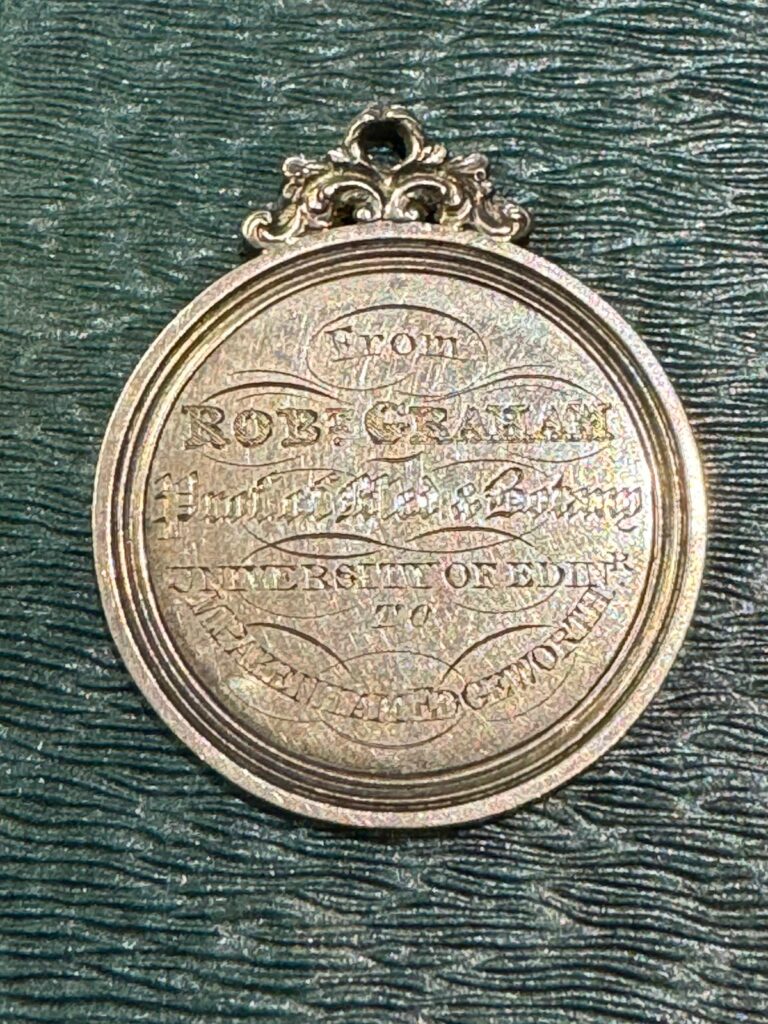

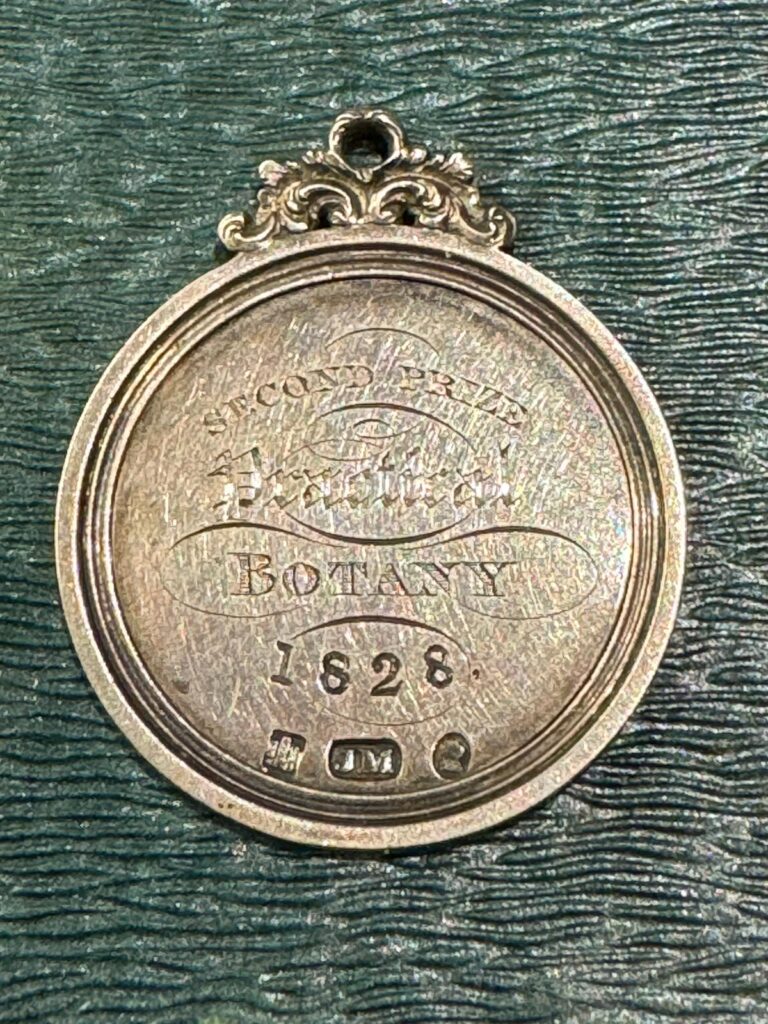

Michael Pakenham Edgeworth came from a cultured and distinguished Irish family. The the last of 22 children of the polyphiloprogenitive Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1744–1817) by the last of his four wives: at his birth his father was 68 and his eldest half-brother was his senior by 48 years. Richard Edgeworth was a politician, educational writer and inventor; a member of the Lunar Society. One of Edgeworth’s much older half-sisters was the novelist Maria (1768–1849) one of whose full sisters, Anna Maria (1772–1824), married the radical Bristol physician Thomas Beddoes (1760–1808), a close associate of Coleridge and Humphry Davy. Beddoes had studied medicine in Edinburgh and taken John Hope’s botany class in 1781. Henry Edgeworth (1782–1813), a son of the third marriage, would also study medicine at Edinburgh, including botany under Daniel Rutherford in 1802. 25 years later Henry’s youngest half-brother would also cross the Irish Sea to Edinburgh to study botany under Robert Graham and oriental languages. In 1828 Edgeworth won a silver medal as Graham’s second prize for practical botany.

After Edinburgh he attended the East India Company college at Haileybury, was appointed a writer to Bengal, and reached India in September 1831. Over the next seven years he held Revenue and Political appointments in Farrukhabad and Ambala. In May 1838 he was appointed Deputy Collector at Muzaffarnagar, from where he took sick leave in Mussoorie that resulted in the work to be discussed below.

Following the Mussoorie sojourn Edgeworth’s next appointment, in December 1838, was to Firozpur, after which came Political and Judicial posts in Ludhiana, Mathura and Delhi before becoming Joint Magistrate and Deputy Collector of Saharunpur in April 1840. He had already been corresponding with Hugh Falconer, Superintendent of the Saharunpur Botanic Garden, and the pair must have had many discussions on botany and other scientific subjects before Edgeworth’s return to Britain on sick leave in February 1842.

Over the four years of this leave Edgeworth developed his interest in photography. His family were already friends of Sir David Brewster, whom he visited in St Andrews in November 1843 and possible on other occasions. An album of calotypes assembled by Brewster (now in the Getty Museum) contains photographs taken by Edgeworth himself around the family seat at Edgeworthstown in Co. Longford and a calotype portrait taken by Dr John Adamson in St Andrews, which shows Edgeworth to have been decidedly good looking. Another interest shared with Brewster was microscopy, which would culminate in 1877 in a book on pollen.

During his leave Edgeworth interacted with metropolitan botanists and in 1844 gave his herbarium of 2000 specimens, mainly collected by himself in the Himalayas, to George Bentham. (The date on the printed label is that of the donation, the specimens must date from 1832–41). Bentham helped to get the specimens named and on 3 June 1845 Edgeworth read a paper on 145 of the most interesting, most of them new species, to the Linnean Society of London of which he was elected a Fellow. Towards the end of his leave, on 17 February 1846, in the ancient cathedral of St Machar, Aberdeen, Edgeworth married Christina Macpherson, daughter of Dr Hugh Macpherson (1767–1854) Sub-Principal of nearby King’s College. The couple had two daughters of whom only one, Harriet, survived.

Second Indian period and retirement

In 1846 the Edgeworths returned to India. Following the annexation of the Punjab by the EIC and the deposing of Duleep Singh in 1849, he ended his career as one of the Commissioners for the settlement of the Punjab, initially based in Multan then in Jullundur. In 1859, due to ill health, Edgeworth retired to Britain.

During retirement the family lived mainly in London, but during several summers they visited Christina’s sister Isabella Macpherson who lived largely on Eigg, which had been purchased by their father in 1827; the house, converted from two cottages, was called ‘The Crow’s Nest’. Dr Macpherson was partly brought up on Skye by his kinsman the Rev Martin Macpherson of Sleat, brother of Sir John Macpherson one-time Governor-General of India (and possible discoverer of Eriocaulon on Skye). He was clearly a considerable scholar and had studied medicine in Glasgow, London and Paris before graduating MD from Edinburgh in 1794, which may mean that he studied botany under Daniel Rutherford. In Aberdeen he became Professor or Oriental Languages, then of Greek, before ending as Sub-Principal of King’s College. Despite being its laird Macpherson never visited Eigg, which was managed for him by a factor who was responsible for the clearance of 14 families in 1853 and further ones in 1858.

Extensive details of Edgeworth’s life, including the visits to Eigg, are to be found in his diaries, which cover the period 1828 to 1867 and are preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. While not possible to enter into details here it is of note that it was on the island that Edgeworth died, on 30 July 1881. His place of burial is unknown – was his body taken back to London, or even to Edgeworthstown?

Edgeworth the taxonomist

Edgeworth’s botanical work in India has been largely forgotten, other than through two shrubs that bear his name familiar from British gardens and conservatories – Edgeworthia grandiflora, a golden-flowered Daphne-relative, and the fragrant, though not completely hardy, Rhododendron edgeworthii. In addition to these he is commemorated in specific epithets in at least 29 other genera.

Users of J.D. Hooker’s magisterial, and still essential, Flora of British India will, however, also be familiar with his name as in retirement Edgeworth authored for its second part (1874) the account of the small family Frankeniaceae and, with Hooker, those of Caryophyllaceae, Zygophyllaceae and part of Geraniaceae. His major solo taxonomic works were published in the Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal and the Transactions of the Linnean Society.

The extent of his contribution, as revealed by the number of species described solo or jointly with Hooker comes as something of a surprise, with at least 15 genera and more than 400 species. At least some of these have stood the test of time, though he appears to have had a rather narrow species concept, and not always referred adequately to earlier literature; many that are still recognised have been transferred to other genera.

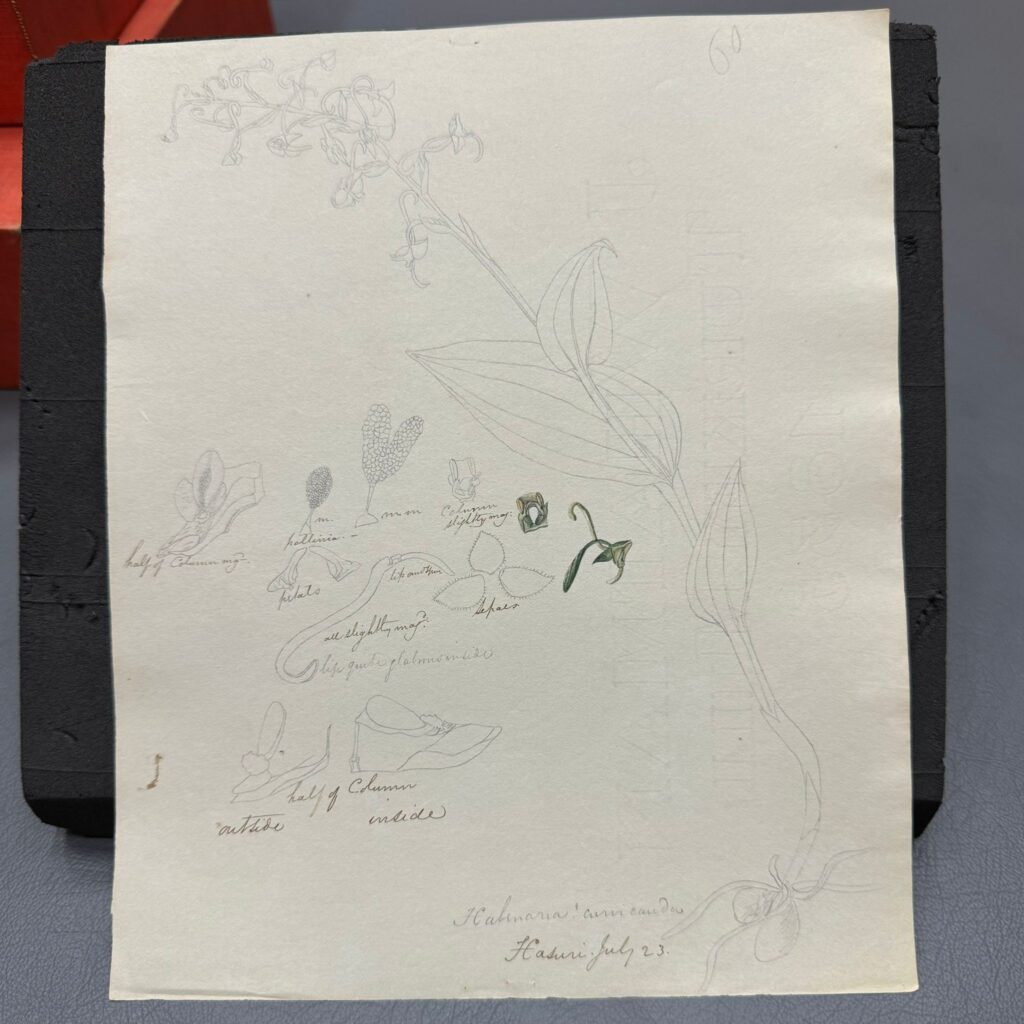

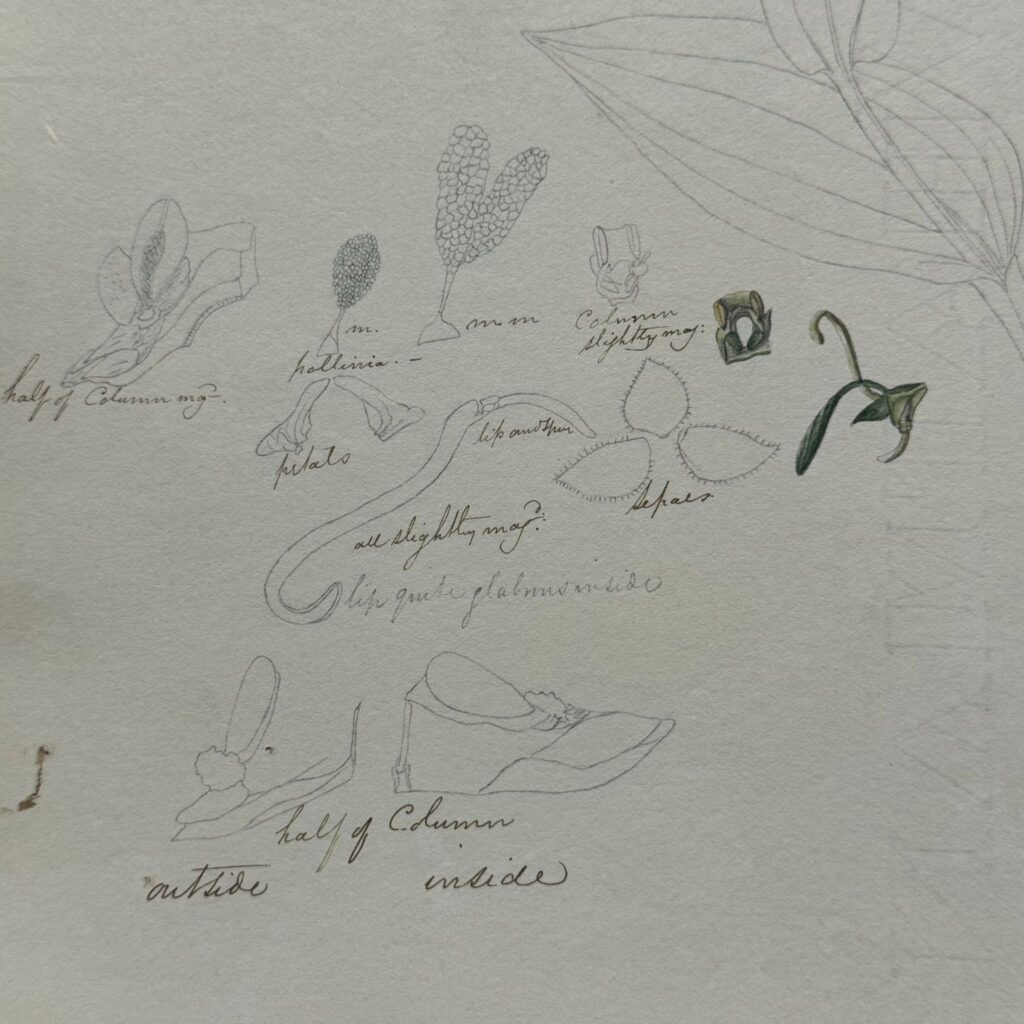

Botanical drawings

It was even less well known that while in India Edgworth made a significant number of botanical drawings. I first became aware of these while cataloguing the Robert Wight collection at Kew, in which are four drawings of flowering plants by Edgeworth, delicately executed in pencil with only a few watercolour details. 78 similar works were then found in Wight’s ‘reserve’ collection of drawings at the Natural History Museum. Edgeworth knew of Wight’s great illustrations project and while in Mussoorie in July 1838 received one of the early parts of his Illustrations of Indian Botany. It would appear that Edgeworth’s entire collection of Himalayan drawings of flowering plants was sent to Wight in Madras, doubtless with the hope that he would publish many of them. However, Wight would publish only six in his Icones Plantarum Indiae Orientalis (four in 1840, two in 1853).

Herminium edgeworthii

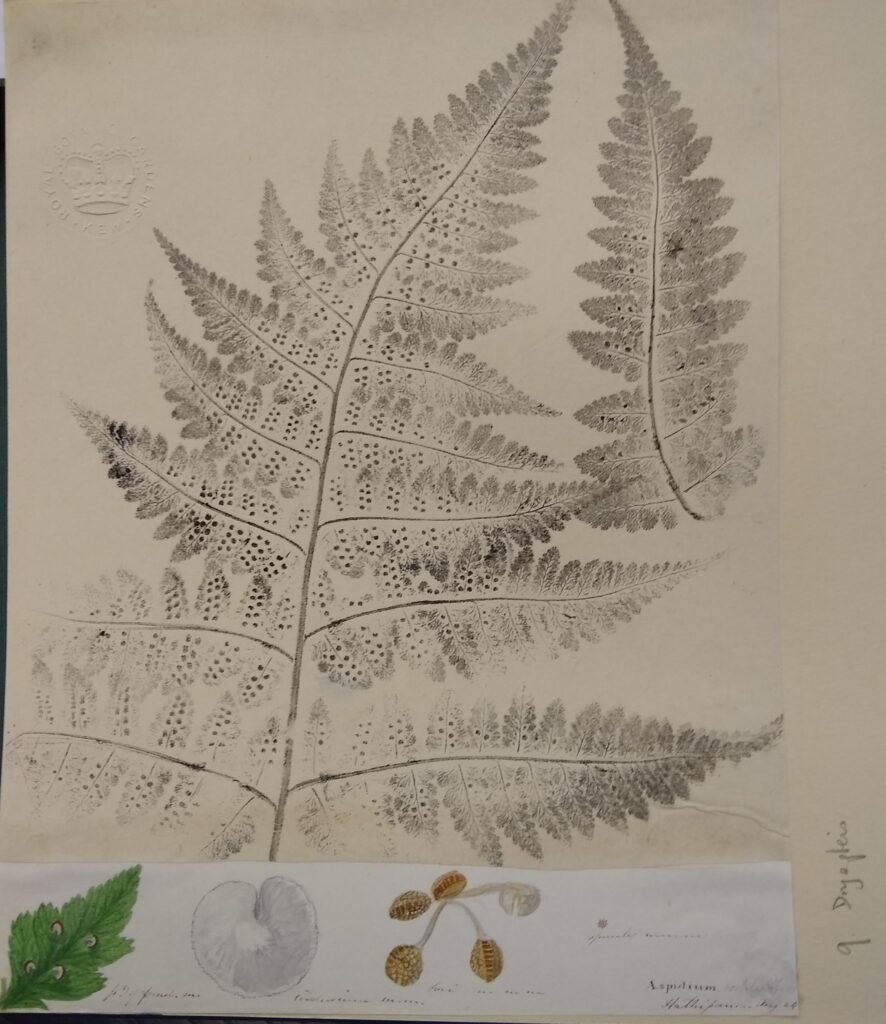

At Kew a group of 21 unsigned illustrations of ferns has recently also been identified as being by Edgeworth. The realisation came from the handwriting, and the unusual name of one of the localities, Hathipaon, while re-examining the numerous Indian drawings reproduced in Ocean Flowers (Armstrong & De Zegher, 2004). These are collages using two distinct media: nature prints to which drawings of magnified details are attached. It is not recorded how or when these reached Kew, but they are likely to have been given by Edgeworth to Sir William Hooker, whose pteridological interests were well known through his publications (many co-authored by Robert Kaye Greville).

Dryopteris caroli-hopei

It turns out that the drawings of both ferns and flowering plants were made around Mussoorie during an intense period of activity in the latter part of the 1838 monsoon season, between July and early September. The story behind them is to be found in considerable detail in Edgeworth’s diaries. Although the small, closely written handwriting on thin paper (folded and probably posted home to his family in Ireland) is hard to read, the gist as it relates to the botanical drawings and nature prints can, nonetheless, be made out.

A productive leave in Mussoorie

While employed in the EIC civil service post as Deputy Collector in Muzaffarnagar in the Gangetic Plains of what is now the state of Uttar Pradesh, Edgeworth must have fallen sick and, probably at the end of June 1838, went to the sanatorium established by the EIC in 1827 at Landour near Mussoorie. One Sunday Edgeworth describes 25 leeches being applied (on medical instruction), which meant that he ‘could not go to church, but instead was tormented with those nasty creeping things’. He turned, instead, to Southey’s Life of Cowper and to a letter received from Kashmir, where Hugh Falconer had ‘made glorious discoveries of flowers – how I wish I could have been with him’.

Like his father and many of his half-siblings Edgeworth was possessed of great intellectual curiosity and numerous activities are recorded in the diary. In addition to the botanical work to be described below this included socialising, playing games of chess and cards (piquet) with friends, probably fellow invalids, going for rides on his pony Saladin and reading the latest European and American literature. Among works listed are I Promissi Sposi (Alessandro Manzoni’s classic, read in Italian), The Black Watch (a novel of 1833 by Andrew Picken), Robert Southey’s Life and Works of William Cowper and ‘Whewell’ (doubtless William Whewell’s History of the Inductive Sciences). The ‘Red Box’ a ‘most stupid story’ by ‘the American Miss [Eliza] Leslie’, however, didn’t quite cut the mustard. There was also music and on 18 July Edgeworth ‘rode out to call on Mr Bontein [see below] – & heard his Seraphine – what a magnificent thing it is!’ It is rather extraordinary to think of some of the strange artefacts being carted up to Mussoorie at this date, a seraphine being a ‘cross between a reed-organ and an accordion’ invented by John Green of Soho Square and patented only five years earlier, in 1833.

In 1832 Mussoorie had been chosen by George Everest, Surveyor General of India and Superintendent of the Great Trigonometrical Survey, as his rainy-season base, from which to complete the great work of geodesy so graphically described by John Keay. Everest had purchased a 600-acre estate at Hathipaon (‘elephant foot’) at 6,500 feet on the limestone ridge three miles west of Mussoorie, on which the original owner, Lieutenant Colonel (later General) William Sampson Whish of the Artillery, had built Park House (‘The Park’) in 1829/30. The house stood on a precipitious site that, when the weather was clear, had spectacular views down to the ‘Dhoon’ below. As the monsoon progressed the rocks became ‘most beautifully festooned with flowers azure, violet, crimson-purple, white, pink &c &c’. In the grounds were several smaller houses, built to accommodate Everest’s staff including the (human) ‘computers’. One was called Logarithm Lodge ‘4/10 of a mile’ to the west: Edgeworth was very precise and it was to ‘Log Lodge’ that he would repair for several periods during his sick leave, and where many of the drawings and nature prints were made.

While the sanatorium was at Landour on the eastern side of Mussoorie, Edgeworth found his way to the Park for the first time on 2 July 1838. The company must have been stimulating, with frequent meetings with Everest and his clever young assistants. Those named by Edgeworth are Bontein, Renny, Logan and Radhanath. John Bontein (1809–1878) was a lieutenant in the Bengal Infantry. Thomas Renny (later Renny Tailyour, 1812–1885) a captain in the Bengal engineers who inherited the estates of Newmanswalls and Borrowfield on the northern edge of Montrose. Magdalen, one of the Captain’s grand-daughters, was an aunt of the Angus botanist Ursula Duncan. George Logan (1809–1854) was a civilian from Duns. Edgeworth was right to be impressed by the Bengali mathematician Radhanath Sikdar (1813–1870), as it was he who would later be the first calculate the height of Mount Everest.

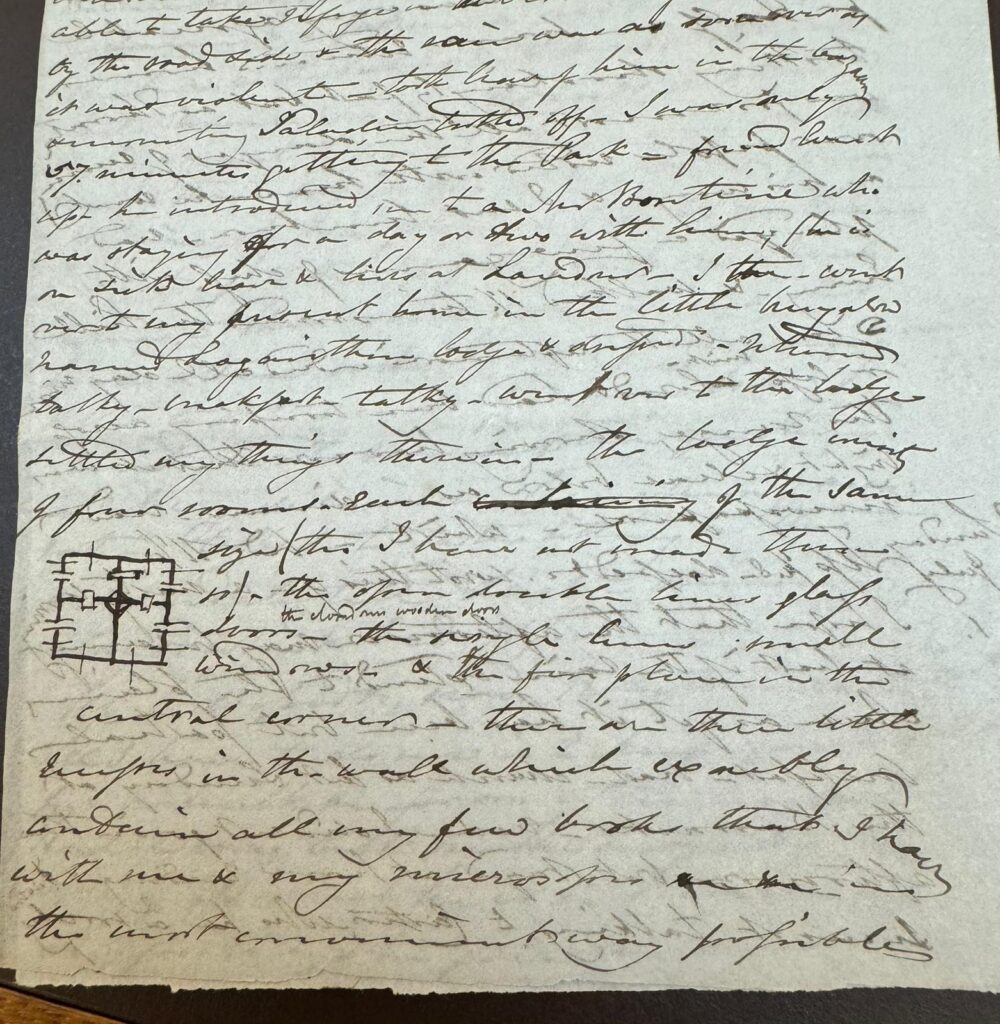

Edgeworth’s diary with plan of Logarithm Lodge

Logarithm Lodge had four rooms around a central chimney stack, with ‘three little recesses in the wall which exactly contain all my few books … & my microscopes in the most convenient way possible’. Meals were often taken in the big house, where the talk can’t all have been intellectual and on one occasion Edgeworth had to sit through a puppet show (‘Katpootli Nabch’), which he found ‘inexpressibly tiresome’ but for the expressions of wonder on the faces of the servants who were allowed to watch. The stays at Hathipaon continued through July and August and seem to have been resumed briefly after a ‘Hill Tour’ that occupied the first three weeks of September.

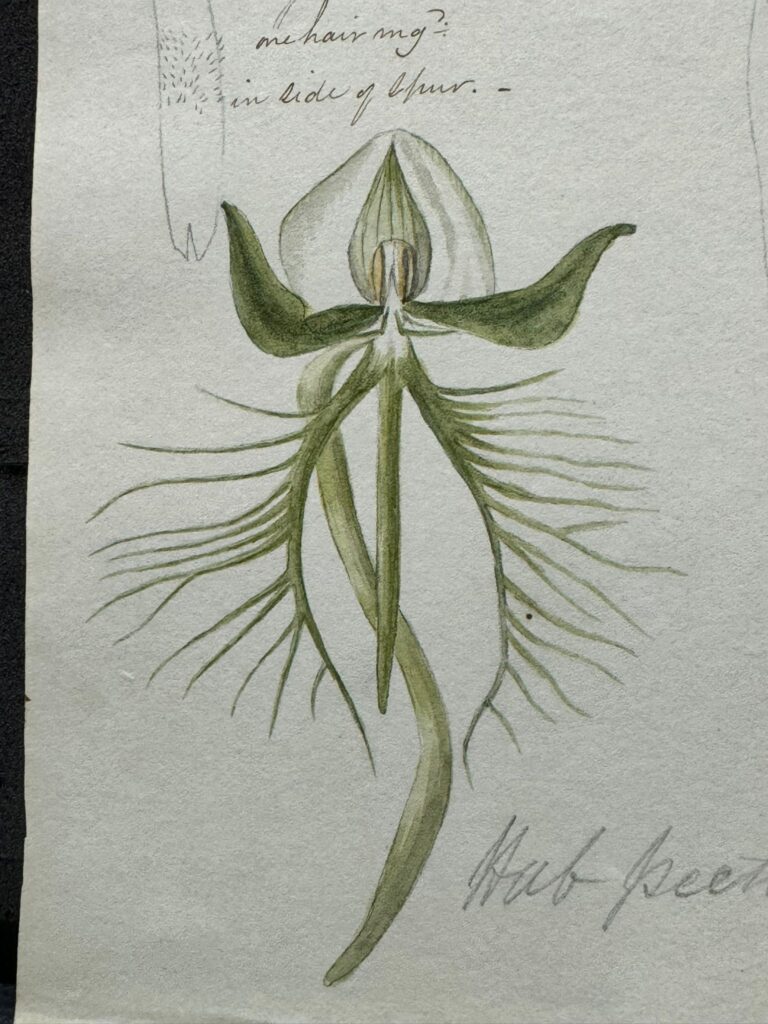

Habenaria intermedia

Botanical work

By 1838 Edgeworth was already a keen botanist, and while in Mussoorie completed a paper on the flora of the Sikh States that would be published that September in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Isaac Burkill credited this as ‘the first ecological paper published in India’, in which its author, as a result of his administrative role, ‘focused his attention on the relations of crops to soils, and then, extending his interest to the relations of the spontaneous plants to the same soils’.

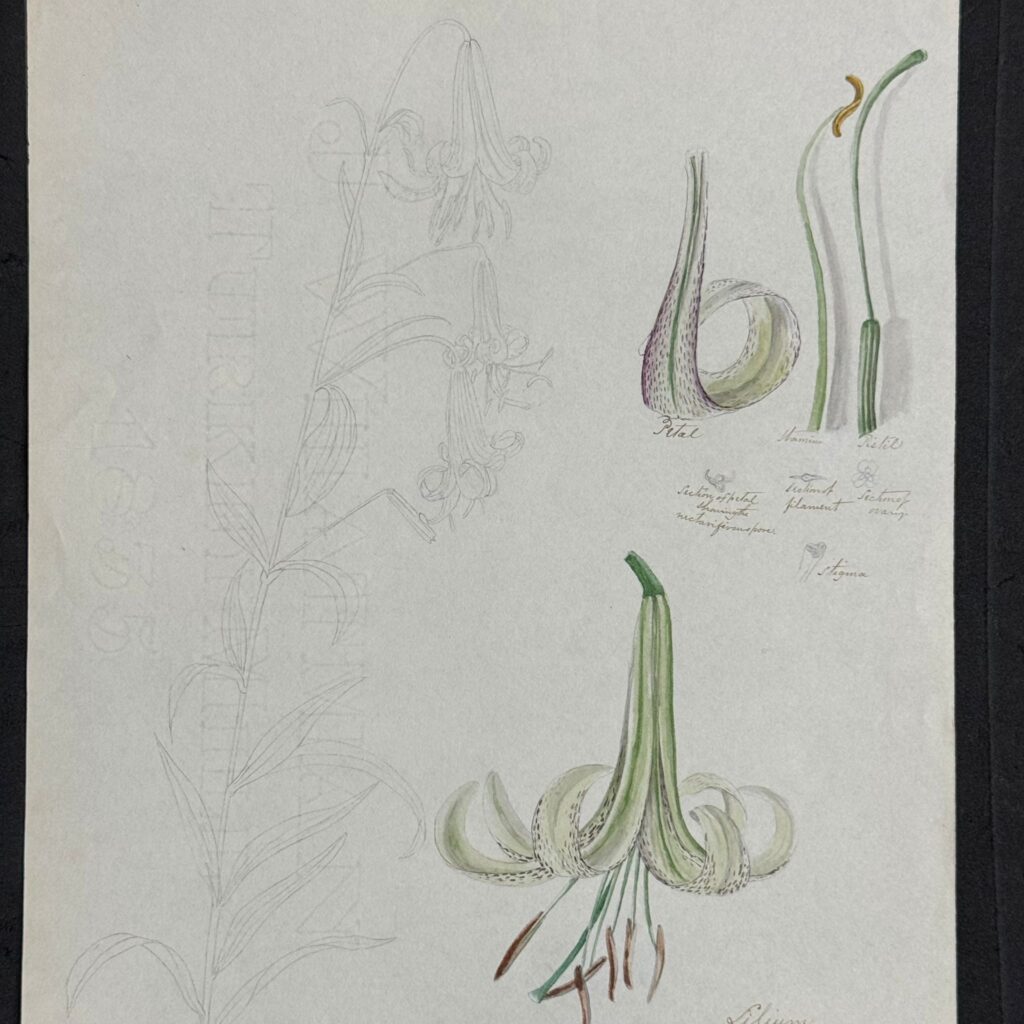

Lilium polyphyllum

In the diary Edgeworth notes spending many hours drawing flowers, aiming for a ‘quantum of 3’ per day. Some of the plants depicted were found by himself during walks and rides, but he also employed a collector who brought one prize, the beautiful ‘spotted lily’ Lilium polyphyllum, from Chamoli. The drawings are in delicate pencil, with only a few diagnostic parts such as flowers in watercolour; analytical details, including pollen grains, were added with the help of a microscope. This is a remarkable body of work – at least 84 numbered flowering plants and 21 ferns in only about ten weeks, and under poor light conditions.

Iris decora

For six of the drawings Edgeworth made an ink copy with a rather scratchy pen, perhaps of ones he tok to be of particularly interest and intended to send to others: Iris decora (NHM), what he considered to be four species of Myriactis (Linnean Society) and Remusatia pumila (K). In Mussoorie he continued to add to his already considerable Himalayan herbarium (later given to Bentham), but these specimens went mouldy as it rained almost every day. He had with him at least two microscopes, an older one described as his ‘rattletrap’ and a newer one ‘with the highest power of which I see a more distinct outline & colour … than with the lowest of the other’.

Another activity undertaken during this productive leave was to copy out parts of Wallich’s Plantae Asiaticae Rariores. This came about by the chance visit to the hill station of Walter Ewer, a judge from Allahabad, whom Edgeworth learned had a copy of the rare and precious work: ‘I hoped I might get a glimpse of it – he has lent it to me – galloped home in great glee’ and ‘commenced a laborious task of copying all that I require for use’.

The fern collages

It was on 15 August 1838 that Edgeworth learnt a new illustration technique. This took place on a visit to a Captain Angelo, though it is not known to which of three men of this rank then in the EIC army (Richard, John or Frederick) this refers; all were presumably grandsons of the remarkable fencing master and equestrian Domenico Angelo Tremamondo. Staying with Angelo’s was a Mrs Marsh who must have had botanical interests as Edgeworth had lent her his copy of Royle’s Illustrations. The wording of the diary is not conclusive, but strongly suggests that it was Mrs Marsh who taught Edgworth ‘how to take impressions of leaves with lamp black and oil’. The lamp black was presumably obtained by scraping soot from the shades of oil lamps, but the variety of oil that it was mixed with is not specified. Mrs Marsh may have been the wife of Lieutenant Hippesley Marsh of the Third Light Cavalry, born Louisa Harriot Cunliffe, daughter of Sir Richard Henry Cunliffe Bt. of Acton Hall, Denbighshire, who had married Marsh in India three years earlier.

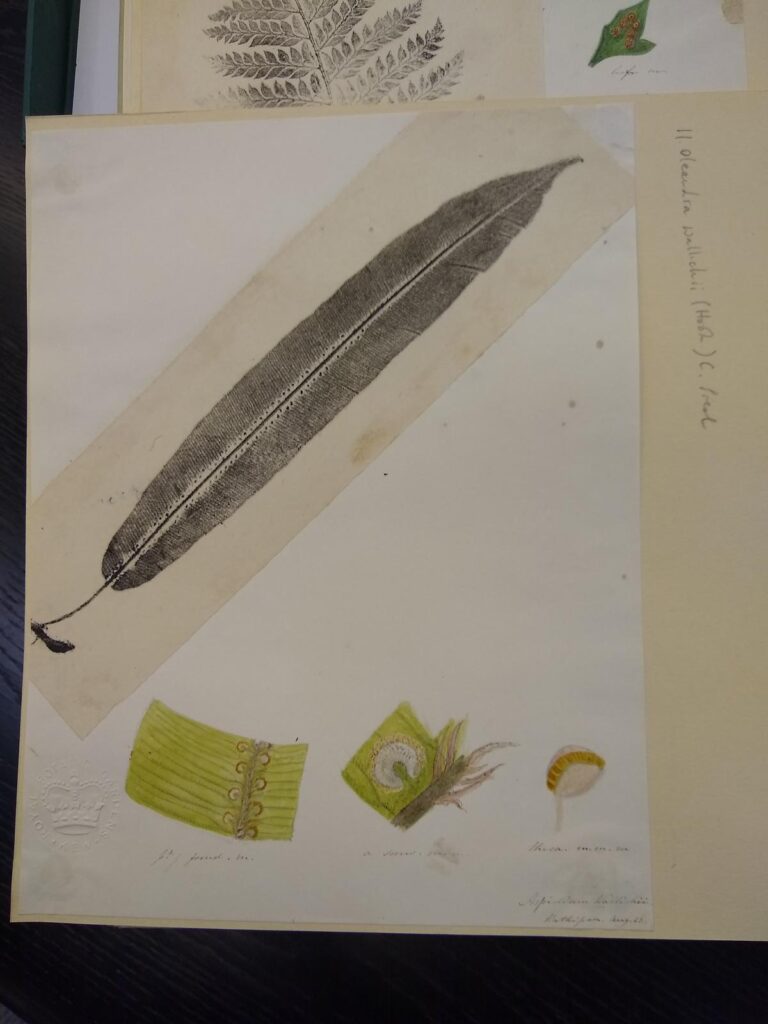

Oleandra wallichii

The collages are on a cream, wove paper, that seems to have come from an exercise book with pink-dyed foredges. These have been cut down and stuck to a lighter, paler-coloured paper on which the watercolour and pencil/ink details were then drawn.

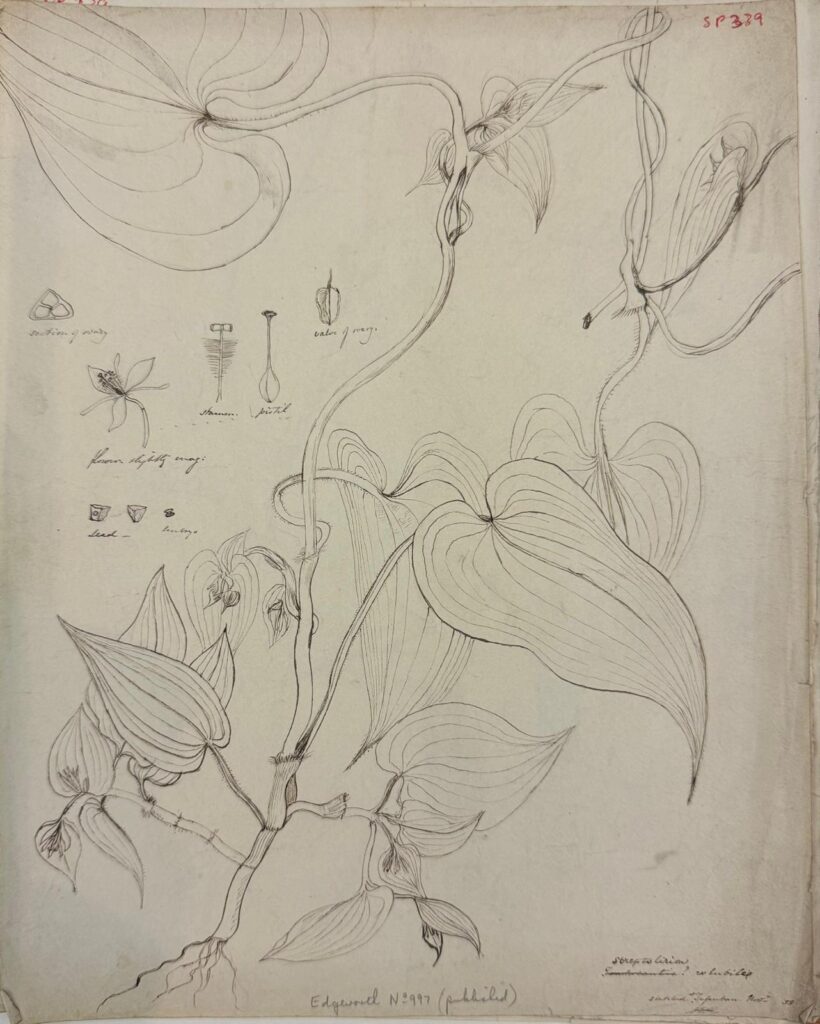

Fate of the drawings

It would seem that Edgeworth gave virtually all of his drawings to Wight and Hooker and kept copies of only five. When he came to publish his major taxonomic paper in the Transactions of the Linnean Society in 1846 only a single drawing was reproduced – from one of the few copies he had evidently kept. It depicts the interesting and unusually climbing member of the family Commelinacae, Streptolirion volubile, and was engraved (very truthfully to the original) by Edward Smith Weddell. The ink copy drawing survives in the Linnean Society archives and with it are four unpublished ones of Myriactis species, ink copies of originals in the Wight collection. At the time of Edgeworth’s publication the majority of the drawings were still in Madras with Wight so would have been inaccessible to him, and it seems a pity that Wight didn’t publish more of them in his Icones.

Streptolirion volubile

Post Script

Immediately after posting this blog my friend, the expert genealogist, Margie Frood solved the mystery of Edgeworth’s place of burial. Not London, not Edgeworthstown, but the Dean Cemetery less than half a mile from my flat! I raced there and spent a couple of hours trying to find it but gave up, went home and phoned John, the graveyard’s very helpful custodian. Ten minutes later I was back, met him in front of his house by the gate and he said “I can’t possibly charge £10 for showing you this” pointing only a couple of yards ahead to a grave I must have passed dozens of times on visits to the numerous inhabitants with Indian connections. The stone is a ‘low monument with hipped top, on a stepped base’ (type 0555 of the national classification of grave markers). The lettering is in raised lead, and the pink Peterhead granite must surely have been chosen by Edgeworth’s widow Christina as a memory of her Aberdeenshire childhood. She was to join him only nine months later, though like her husband her corpse had to travel some distance, though she came from the other direction, having died in Bournemouth.

Further reading

For the Macphersons and MPE on Eigg see https://www.eigg-history.org/index.asp?pageid=714828 (consulted 18 November 2024)

Edgeworth’s diaries at the Bodleian are at MS. Eng. Misc. e. 1471

Armstrong, C. & De Zegher, C. (eds) (2004). Ocean Flowers: Impressions from Nature. New York & Princeton: The Drawing Center and Princeton University Press.

Burkill, I.H. (1965). Contributions on the History of Botany in India. Calcutta: Botanical Survey of India.

Keay, J. (2000). The Great Arc: the Dramatic Tale of how India was Mapped and Everest was Named. New York: Harper Collins.

Phillimore, R.H. (1958). Historical Records of the Survey of India. Volume IV 1830 to 1843 George Everest. Dehra Dun: Survey of India.

Prinsep, H.T. (1844). A General Register of the Hon’ble East India Company’s Civil Servants of the Bengal Establishment from 1790 to 1842. Calcutta. Baptist Mission Press. [Covers the whole of Edgeworth’s first Indian period]

Smith, G. (1990). Disciples of Light: Photographs in the Brewster Album. Malibu: The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Ketaki Godbole

Very interesting article Mr. Noltie..so much still remains to be discovered about this era of Indian colonization. While researching at my job at the Empress Botanical garden, in Pune India, I discovered that it was blessed with 2 Superintendents from Kew.. George Marshall Woodrow and Amos C Hartless.

Actually it would be really good if we could connect over email regarding this research work.