By Jennifer Baker, a conservation horticulturalist from the Scottish Native Plant Recovery Team. Fascinated by the complex life cycle of the One-flowered Wintergreen, Jennifer set up a three-year project researching the fungal partners the plant needs to survive in the wild. The project is supported by Scottish Native Plant Recovery Horticultural lead Rebecca Drew-Galloway, the Cairngorms National Park Authority, Sam Jones from PlantLife Scotland, RSPB Abernethy and Forestry and Land Scotland. Here Jennifer describes the plants interactions and the reasons behind the project.

Deep within Scottish pine woods, nestled between humid mossy carpets and scattered pine brash on the forest floor, the story of a tiny, unassuming plant: the One-flowered Wintergreen (Moneses uniflora), is beginning to unfold. Beneath its solitary, nodding white flower, and small rosetted leaves, lies a hidden, intricate survival strategy sheathed within the soil.

This captivating little plant is currently Red listed in the UK, meaning its critically endangered and at risk of extinction. Once common across ancient Caledonian pine forests, the One-flowered Wintergreen now persists along forestry tracks within commercial plantations of Scots and Corsican pine. Remaining populations are limited due to habitat loss and fragmentation resulting from climate change, intensive forestry, and changes in agricultural practices, all of which impact the essential microbial life in the soil.

The Mystery of Mixotrophy

The One-flowered Wintergreen is an intriguing example of a mixotrophic plant. This means it can photosynthesise, like most plants, but crucially, also relies on mycorrhizal fungi for vital nutrients. This dual survival strategy is essential early in the plant’s life cycle.

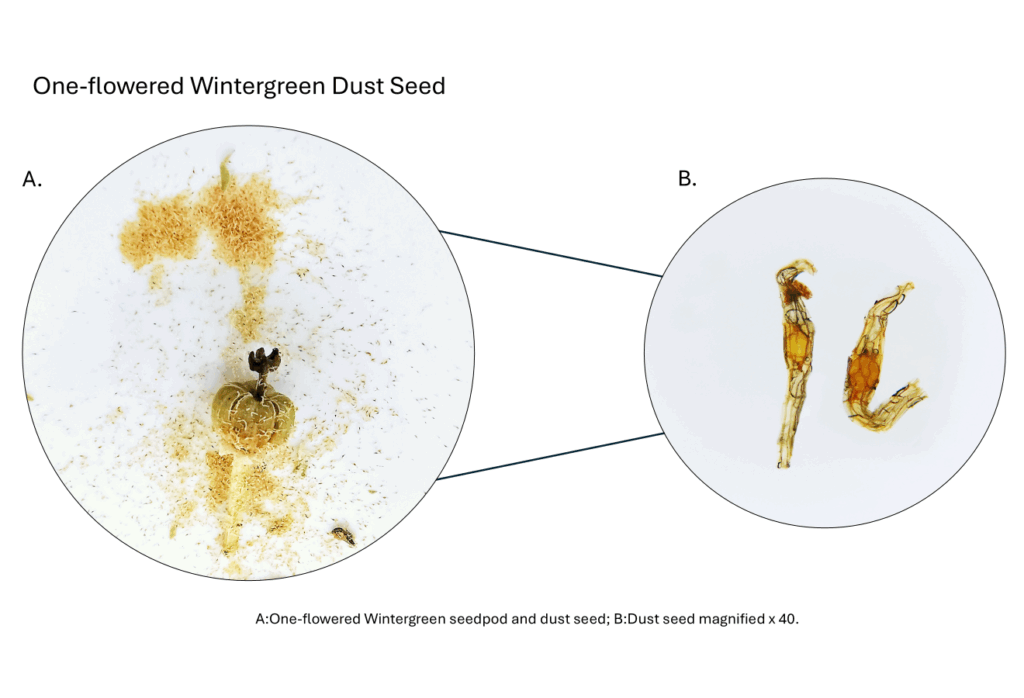

Like a terrestrial orchid, the One-flowered Wintergreen produces large numbers of tiny, dust-like seeds with minimal nutrient reserves. Limited internal resources mean the seed can’t develop fully on its own. Instead, the plant has evolved a survival strategy called initial mycoheterotrophy. This makes it dependent on mycorrhizal fungi to provide the carbohydrates (sugars made through photosynthesis), water, and minerals needed for the seed to germinate and a seedling to establish. This interaction safeguards the plant by overcoming a common evolutionary challenge, which is the trade-off between producing many small, easily dispersed seeds while still ensuring enough energy for a seedling to grow.

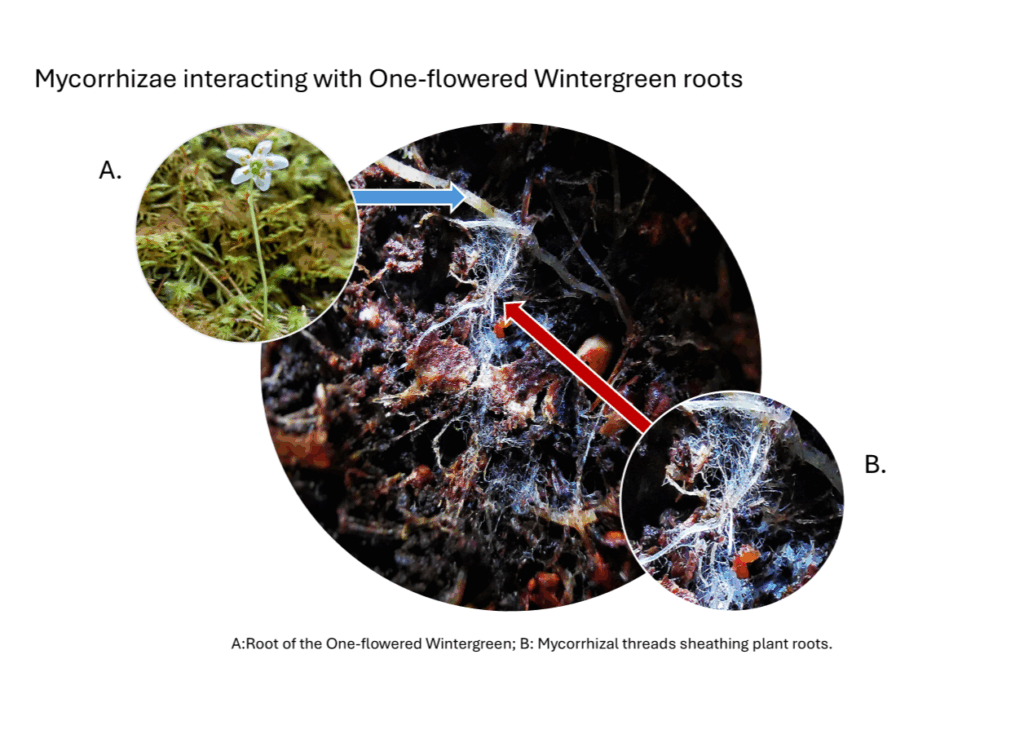

However, for the strategy to work, the seed must encounter a compatible fungal partner in the soil. Plants which rely on mycorrhizal fungi for germination often evolve relationships determined by their microbial soil communities, which makes the pool of compatible partners limited. This reliance on fungal connections makes the One-flowered Wintergreen highly vulnerable to changes in the soil microbiome. And unfortunately, pine woodland fungal communities themselves are under threat from practices like clear-cutting, nutrient pollution (eutrophication), and broader anthropogenic change.

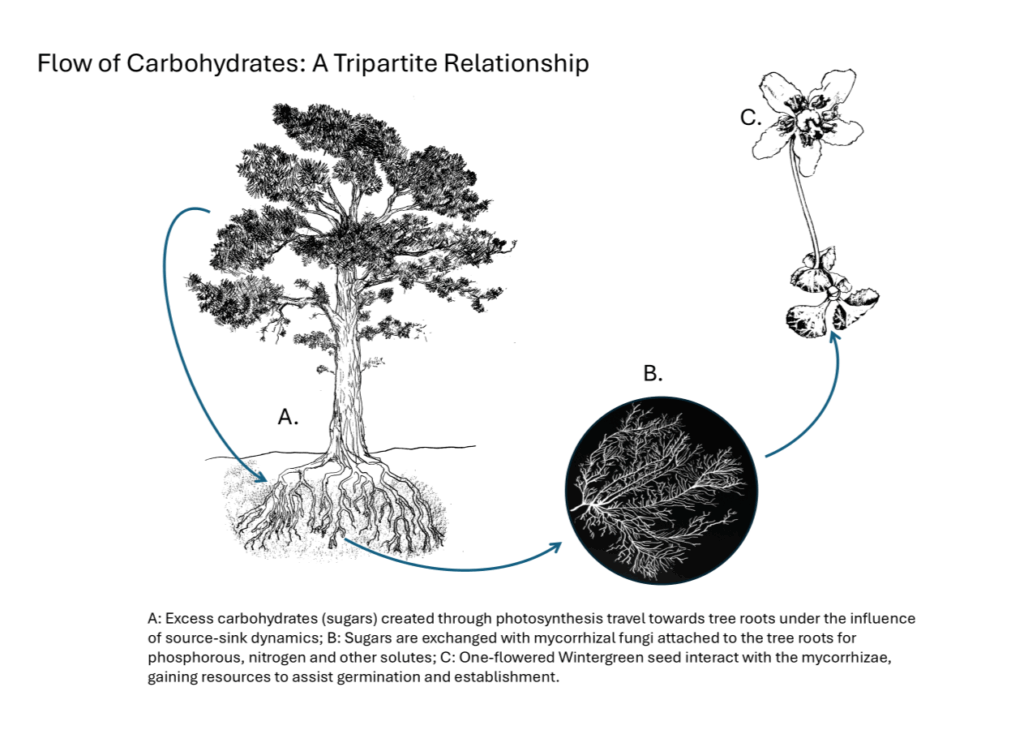

For the One-flowered Wintergreen nutritional acquisition doesn’t just end with mycorrhizal fungi, there is another player in this intricate web. The sugars that the One-flowered Wintergreen receives from its fungal partners must originally come from photosynthesis, a process that mycorrhizal fungi cannot do themselves. So, how do these fungi get essential sugars in the first place? And how does this exchange happen?

In soil nutrient-poor environments like a pine forest floor, ingenuity is key. Mycorrhizal fungi and pine trees have developed a complex underground network of resource movement which exceeds their individual biological limitations in the face of lean resources. The trees, with roots not fine or extensive enough to reach every tiny pocket of nutrition in the soil, are the source of surplus photosynthesised sugar. The sugar is exchanged with mycorrhizal fungi for phosphorus, nitrogen and other minerals the fungi can access more readily. Mycorrhizal fungi use the sugar for their own growth, building delicate thread like structures called hyphae. This increases mycorrhizal biomass, effectively extending the reach of the tree roots, expanding resource access. Additionally, as mycorrhizal networks increase in size, they draw more sugars from the trees, spreading further through the soil and perpetuating this exchange cycle.

One-flowered wintergreen directly benefits from this arrangement, receiving sugars the pine trees have photosynthesised, via the mycorrhizal fungi. This fuels the plant’s germination and establishment. The process is termed a tripartite (three way) relationship, where the essential need for carbon drives these intricate symbiotic dynamics.

The reason mycorrhizal fungi give up sugars to mixotrophic seeds is unclear. One theory suggests that juvenile mixotrophic plants function as parasites, drawing carbon from the mycorrhizal fungi without giving anything in exchange. However, recent studies on the mixotrophic Common Spotted-orchid (Dactylorhiza fuchsii) show that carbon, labelled with ¹⁴CO₂, travelled from exposed adult plants, through shared mycorrhizal networks, to their seedlings, with some sugars remaining in the mycorrhizal fungi. This suggests a “buy now, pay later” dynamic, where mycorrhizal fungi support seedlings, in anticipation of future gains from mature plants. Whether a similar process sustains the One-flowered Wintergreen remains to be seen.

Seed Baiting for Conservation

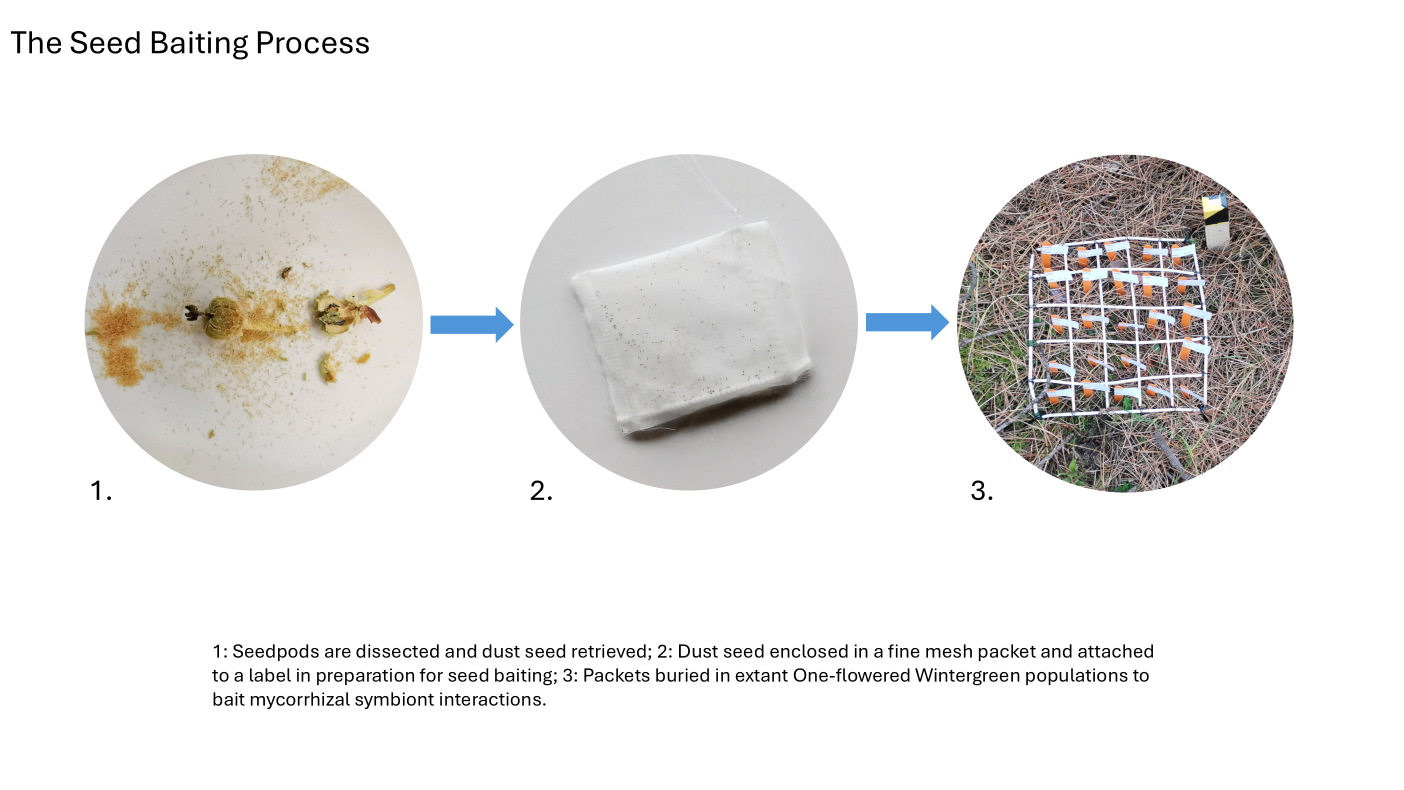

This project aims to identify the mycorrhizal fungi needed for germination in three Scottish populations of One-flowered Wintergreen, while also developing methods to grow the plant ex-situ (out with natural populations, in controlled conditions). We are achieving this using a technique called “seed baiting”.

Seed baiting involves placing tiny dust seeds into fine mesh packets and burying them in plant populations. This allows the seed to interact with native mycorrhizal fungi, kick-starting the germination process. Over two years, these packets will be recovered and divided for different analyses:

- Cultivation: Germinated seedlings will be transferred to pots previously inoculated with substrate from plant populations, also containing juvenile pines, encouraging tripartite interactions.

- In Vitro Culture: Seedlings grown on in culture using micropropagation techniques adapted from those used for orchid propagation.

- Fungal DNA Analysis: Seedlings will be subject to DNA analysis to determine the fungal taxa responsible for initiating germination, ideally to genus or species level.

Our goal is to understand the plant’s life cycle and its essential interactions, with further research planned once a healthy ex-situ collection is established.

Broader Implications

Findings will provide fascinating insights into the secrets of the One-flowered Wintergreen’s mixotrophy. Identifying the plant’s fungal partners should guide suitable site selection for future reintroductions of the plant into the wild. By testing the soil microbiome in potential translocation areas, we can significantly increase the chances of successful population establishment.

While mature plants in the Pyroloideae (the subfamily to which the One-flowered Wintergreen belongs) are known to associate with a diverse species range of mycorrhizal fungi, studies on related species like the Pink Wintergreen (Pyrola asarifolia) show that seedlings rely on specific non-ectomycorrhizal fungi before potentially switching to diverse ectomycorrhizal partners as they mature. Seed baiting will reveal whether the One-flowered Wintergreen follows a similar pattern, interacting with a variety of fungal mycorrhizal species and increasing these interactions throughout its life cycle.

Conservation Value

Fluctuations in mixotrophic plant populations can serve as indicators of broader plant-fugus-soil health, with declines often reflecting disruptions to the underground nutrient exchange networks that support entire ecological communities. Studying these plants is therefore a valuble tool when assessing the condition of pine woodland ecosystems.

By identifying, understanding, and preserving vital symbiotic relationships that sustain mixotrophic species, we can shape conservation strategies that operate across multiple interconnected levels of life. In doing so, we will not only protect a rare and complex group of organisms, but also help safeguard the biodiversity and long-term resilience of pine woodland habitats.

Special thanks to Rebecca Watt at CNPA, Chris Tilbury at RSPB Abernethy, Hebe Carus at FLA, Rebecca Drew-Galloway, Sam Jones, Aline Finger, and Lucy Bains.

Instagram @rbgescottishplants

X @TheBotanics

X @nature_scot

X and Facebook @ScotGovNetZero

Facebook @NatureScot

#NatureRestorationFund