This article was written by Eloise Fenton, graduate of the 2024/2025 RBGE Masters programme in Biodiversity and Taxonomy of Plants.

Building on the role of urban trees in supporting biodiversity, I spent this summer working with the Botanics’ Nature-Based Solutions team on my MSc project, exploring how different tree species support biodiversity in urban environments.

Urbanisation is one of the most significant threats to species survival today, so as cities expand it’s crucial to find ways to support and enhance biodiversity. Creating opportunities for nature in cities is vital for healthy, functioning ecosystems and for people’s wellbeing. Doing so helps reduce the negative effects that urban growth has on species survival around the world.

Appearing as solitary street trees or as part of larger green spaces, trees in cities offer countless benefits. They connect people with nature, improve physical and mental health, help tackle climate change, and act as a living ecosystem that supports a diversity of organisms.

Measuring a tree’s biodiversity value is not straightforward. Biodiversity is complex and multifaceted, involving countless interacting variables. Nevertheless, a new approach to measuring a tree’s biodiversity value has been developed by Trees and Design Action Group through the development of a biodiversity metric. This metric, using evidence and expert data, has so far been used to assign a potential biodiversity value (very high, high, moderate, low) to 66 different tree species. My project aimed to develop and trial methodologies to check the real-world accuracy of this proposed metric.

Summer Tree Research on the Garden Grounds

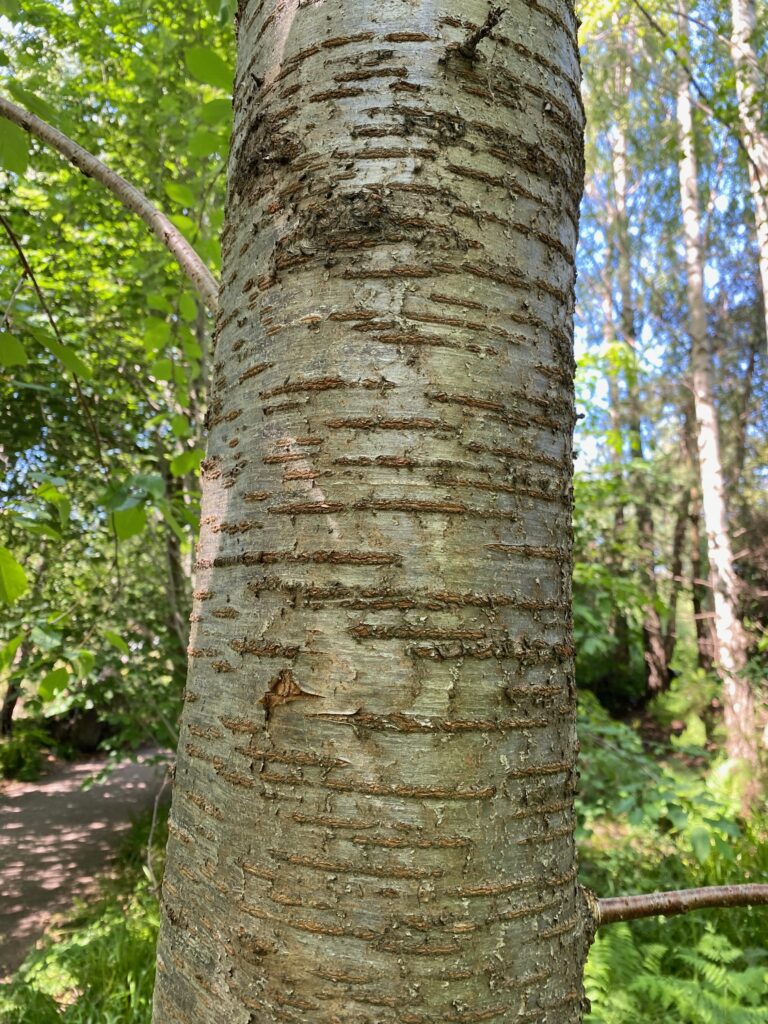

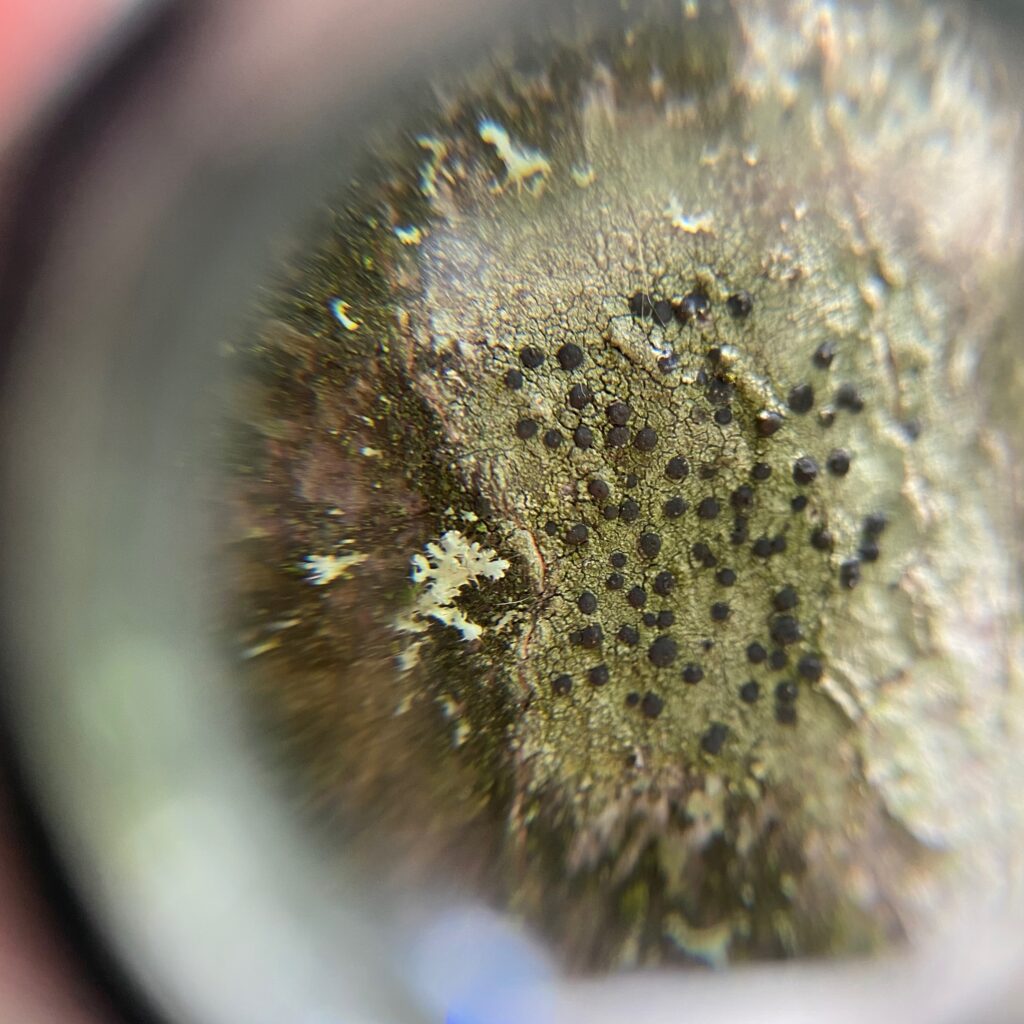

I carried out fieldwork on forty trees at the Edinburgh Botanics, including two species from each of the potential biodiversity categories. For each tree, I studied lichens on the trunk and invertebrates in the canopy and on the bark.

Lichens growing on the trunk were surveyed using a “lichen ladder”.

To study bark-dwelling invertebrates, a black plastic bag was attached to the tree trunk for one week to attract insects that prefer dark, moist habitats like the cracks and crevices of tree bark.

The variety of life observed was striking. In 30 seconds, over a thousand individuals of a single apparent aphid species were collected from the canopy of some trees, while others yielded none. Some trees hosted fewer individuals but a greater diversity of individuals. This raised important questions about the ecological value of different tree species: should we prioritise trees that support high abundance, that support greater diversity, or strive to achieve both?

More than a thousand aphids were sampled from some of the Sycamore trees (Acer pseudoplatanus L.) surveyed.

Both larval and adult stages were recorded, such as moth larvae from the order Lepidoptera.

Differences in bark texture among tree species, and the diversity of life living within the bark’s cracks and crevices, highlighted the importance of considering organisms often hidden from view. Looking beyond what’s immediately visible is essential to appreciate just how much life thrives in potentially overlooked corners of the natural world.

Older, larger trees hosted more lichens, showing how tree age and size – alongside species and habitat – affect biodiversity. Exploring the world of lichens revealed how many interacting factors influence life, from light and air quality to bark chemistry and microclimates. Understanding lichens roles in ecosystems also emphasised the need to include all groups of organisms in biodiversity studies, as each contributes to the intricate ecological networks that sustain ecosystem health.

Can a Biodiversity Metric Assess the Biodiversity Value of Urban Trees?

My research revealed clear differences in the biodiversity supported by different tree species, but these differences varied depending on what was measured: type of organism, number of species, or total individuals. No clear relationship was observed between the proposed biodiversity metrics outcomes and my results, although the study’s small scale limited comparisons.

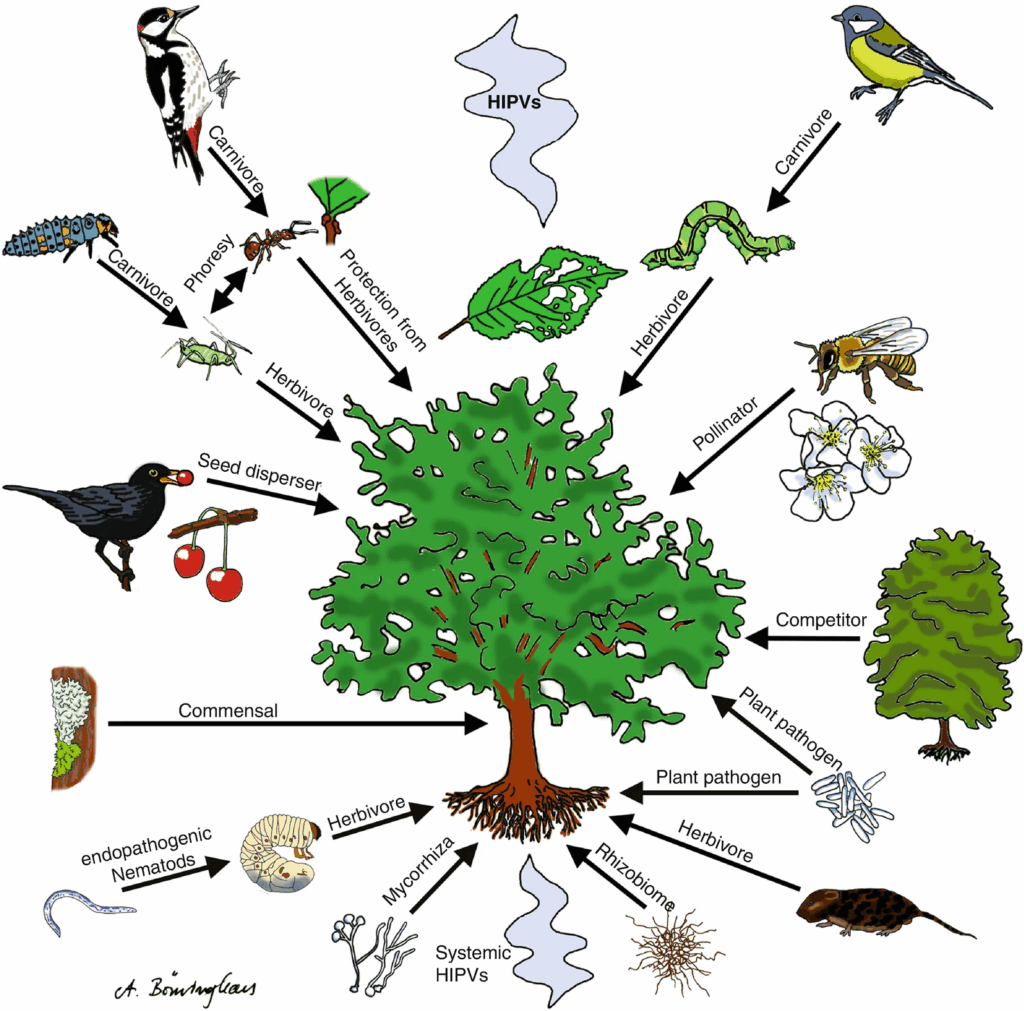

Image adapted from Schulze et al. (2019), Plant Ecology, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

With more data I believe an accurate biodiversity metric can be developed, and that the proposed biodiversity metric is a good starting point. Although the impact of age, ecological, and environmental factors, and the low life expectancy of many urban trees, mean that it is difficult to say this with certainty. Nonetheless, despite its potential impact, a biodiversity metric cannot be used alone, and other factors must be considered alongside it.

Beyond Species Specification – Urban Green Space Enhancement

Firstly, the preservation of old, large trees is essential. The disproportionately large impact that these structures have on biodiversity mean that protecting them, and the planning for their eventual replacement, is vital.

Secondly, the impact of habitat structure and composition on biodiversity needs to be considered. Recent studies focused on determining the key components of biodiversity-friendly habitat design highlight the importance of factors such as different vegetation layers and species diversity. These key factors therefore need to be considered when planning urban spaces for biodiversity enhancement.

Finally, we need to remember people. Humans are key decision makers in urban environments, and meaningful collaboration between scientists, communities, and policymakers is essential to achieving biodiversity goals. Engaging people with nature must go beyond those already living near lush green spaces and needs to include strategies that extend access to nature across the whole city, improving both ecological health and quality of life for everyone.

Urban Trees within the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

At the Botanics, the Nature Based Solutions team is exploring how plants can help tackle the effects of climate change and reduce the ecological impacts of urban environments. Considering the impact of tree species selection can potentially play a key role in this work. Trees offer a powerful way to connect people with nature. Their striking presence in urban landscapes make them ideal for engaging communities. Through education, exposure, and thoughtful planning, this connection can deepen – helping to inspire collective action for greener, healthier cities.