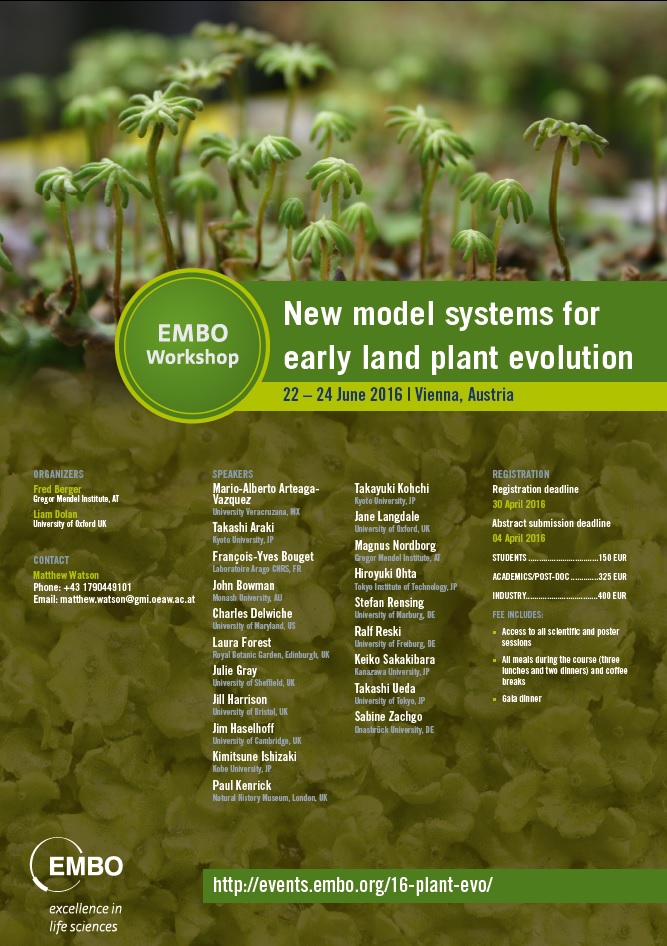

A couple of weeks ago I spent a few days in Vienna, my first visit in 11 years, when I was last over for the 2005 XVII International Botanical Congress. The location was practical – the hotel neatly nestled underneath a main road overpass, but extremely convenient from the airport, only a short train ride, and only minutes’ walk to the workshop venue, the Gregor Mendel Institute, where three days of talks and poster sessions on model early land plants were taking place. Arriving on the Tuesday evening, there was time to catch up with evolutionary biologist Dr Jill Harrison, a friend since our grad student days at RBGE, who has just moved her research group to the University of Bristol. The rest of my evening was spent fiddling with my slides for the talk I was giving the next morning.

Having attended a range of workshops in the past, nothing had quite prepared me for the scale of this one – with around 120 people registered, the large lecture theatre was packed, attendees spilling out to sit on cushions down the stairwells. Workshop organizers Professors Liam Dolan and Fred Berger opened the meeting, followed by a dazzling romp through Arabidopsis genomics from Professor Magnus Nordborg.

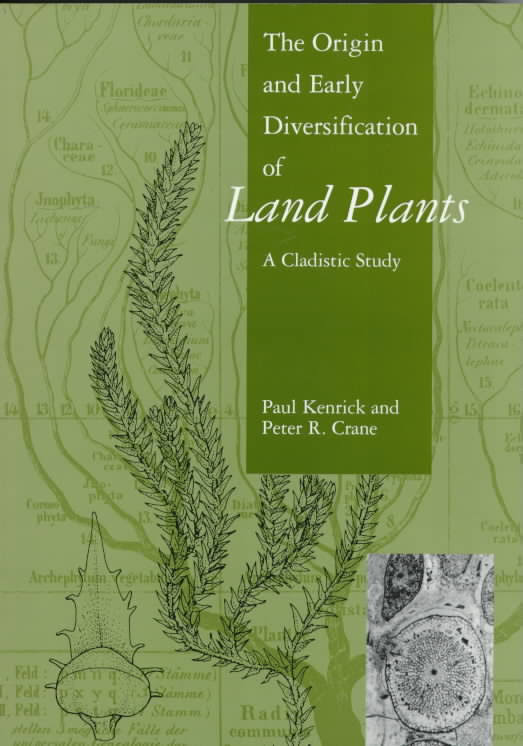

To introduce the next talk, I need a slight digression: If you are interested in land plant evolution, chances are you will have a copy of Dr Paul Kenrick and Peter Crane‘s The Origin and Early Diversification of Land Plants A Cladistic Study somewhere around your workspace. It was published in 1997, and my paperback copy is dog-eared and water-stained, having crossed the Atlantic more than once, and been lugged around various parts of the world in backpacks. My bookmark is still my deposit slip for the book: I ordered it in January 1998 from James Thin booksellers on South Bridge, Edinburgh, which obviously didn’t think local demand would be sufficient to keep copies in stock. (The book is still available to buy; sadly the bookshop went into administration in 2002.)

To introduce the next talk, I need a slight digression: If you are interested in land plant evolution, chances are you will have a copy of Dr Paul Kenrick and Peter Crane‘s The Origin and Early Diversification of Land Plants A Cladistic Study somewhere around your workspace. It was published in 1997, and my paperback copy is dog-eared and water-stained, having crossed the Atlantic more than once, and been lugged around various parts of the world in backpacks. My bookmark is still my deposit slip for the book: I ordered it in January 1998 from James Thin booksellers on South Bridge, Edinburgh, which obviously didn’t think local demand would be sufficient to keep copies in stock. (The book is still available to buy; sadly the bookshop went into administration in 2002.)

More than 18 years after buying and reading his book, this was the first time I’d actually heard Paul Kenrick speak, and it definitely goes down as one of the highlights of the meeting for me. Clear, well paced and interesting, Paul led the audience through a concept of plant models that is very different to Arabidopsis-Physcomitrella-Marchantia.

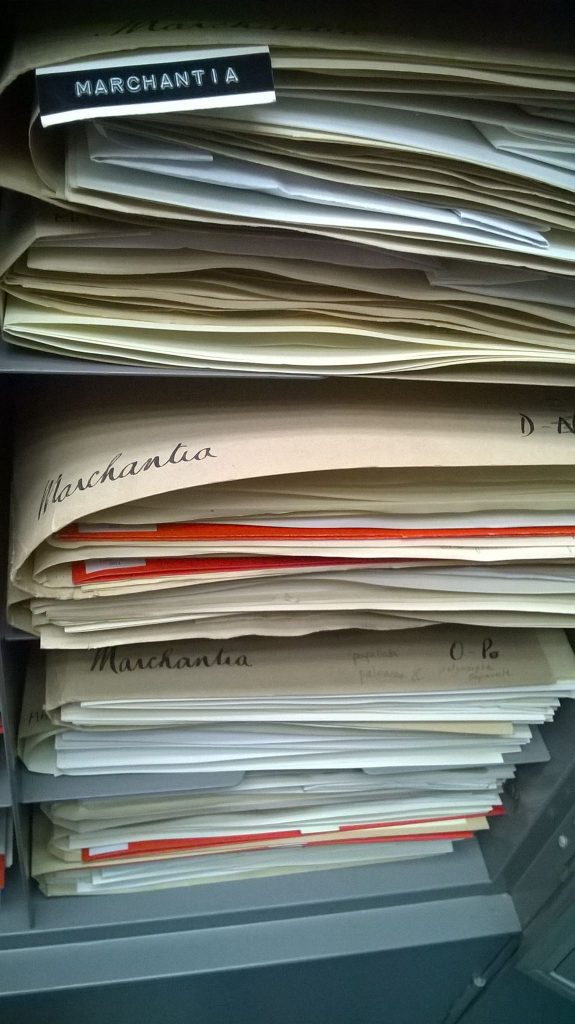

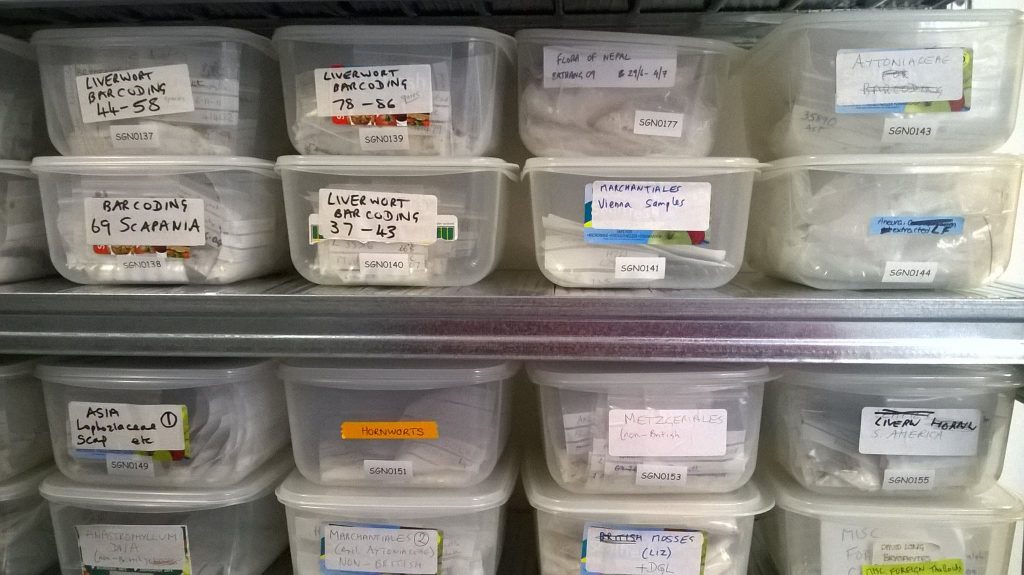

My own talk was a meander through the complex thalloid liverworts. The aim was to highlight the RBGE’s outstanding collection of dead complex thalloid plants, both as herbarium specimens and as silica dried tissue collections, and in addition, to point out some of the amazing non-Marchantia diversity within the group.

If I were composing my talk again today, it would be with an appreciation of two key facts about the audience that had not actually occured to me before the meeting. The first is that the other participants have an astounding understanding of their model plants’ form and function, at a level that far exceeds mine. The second is that an amazing resource of dead plants is not actually all that valuable to the evo-devo community, who are largely interested in what genes are expressed (transcriptomes, from RNA) and in what happens to plant growth when you change things – both of these require living material. Unfortunately, at RBGE we have extremely few bryophytes in the living collections – in fact, only two of which I am aware. We do incidentally have some rather spectacular quantities of Marchantia, although these have largely sprung up unrequested in an untended flowerbed….

As the conference programme and abstracts are available online, however, I won’t go into any more detail about the talks, breaks, posters etc., but pick out a few key impressions. Overwhelmingly, mine are of a vast enthusiasm for experiment-driven natural history. Working out what things do, by trying to turn them off, and comparing that to what happens if you turn them on even brighter… the inevitable question if someone doesn’t mention this: “But have you tried overexpressing it?” Twisted curled balls of plant tissue, proliferating organs, and just general weirdness, all tied in to stories of How the Plant Became. Presentations of beautifully arranged slides, with professional quality illustrations. Internationality at all levels. And approachability.

Sadly, I missed the last day of the meeting entirely, as I had another event scheduled – the Morag Alexander School of Dance annual show in Musselburgh. The show itself isn’t exactly a Once In A Lifetime experience – this one was the 7th annual dance show I’ve been to, but it was my daughter’s first ballet performance (for a few brief moments) on pointe. It did, however, mean missing what looked like a really enjoyable day of talks; in the light of short conversations earlier with both Dr Sebastian Schornack and Duke PhD student Jessica Nelson, theirs were two I was particularly disappointed to miss.

I am very grateful to Fred Berger and Liam Dolan for the invitation to come along and experience something that was, for me, just a little outside my regular molecular phylogeneticist comfort zone, but all the more interesting for that; and to Martina Gsar – the organization throughout was flawless. For the Physcomitrella and Marchantia evo-devo communities I have a short message: our plants may be mostly dead, and good for morphology and DNA only, but we are very happy to work with you in any areas that our fields overlap, and will welcome any of you who chose to visit us. Within the EU, funding to visit and work with natural history collections is available through the SYNTHESYS Access programme.