Jane Wisely, Papaver rhoeas, Failand, Somerset, 25th July 1936, from a collection in the RBGE Archives

John Hatley wasn’t at RBGE very long, joining us on 23rd July 1914 as a labourer at the age of 35. Genealogical researcher Garry Ketchen has been able to give us more information about Hatley’s life prior to this. He was born in Edinburgh in June 1879 to glass cutter Francis Hatley and his wife Catherine. John worked as a baker before enlisting in the army in 1896, serving as a gunner in the 2nd Edinburgh Royal Artillery Militia, being discharged a year later when he enlisted as a regular soldier in the 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers. This led to him seeing action in the South African Boer War in 1899, returning home in 1903. He became a reservist in 1904, finally being discharged in 1909. Possibly amongst other jobs, he became a labourer in a firewood factory before joining RBGE in July 1914.

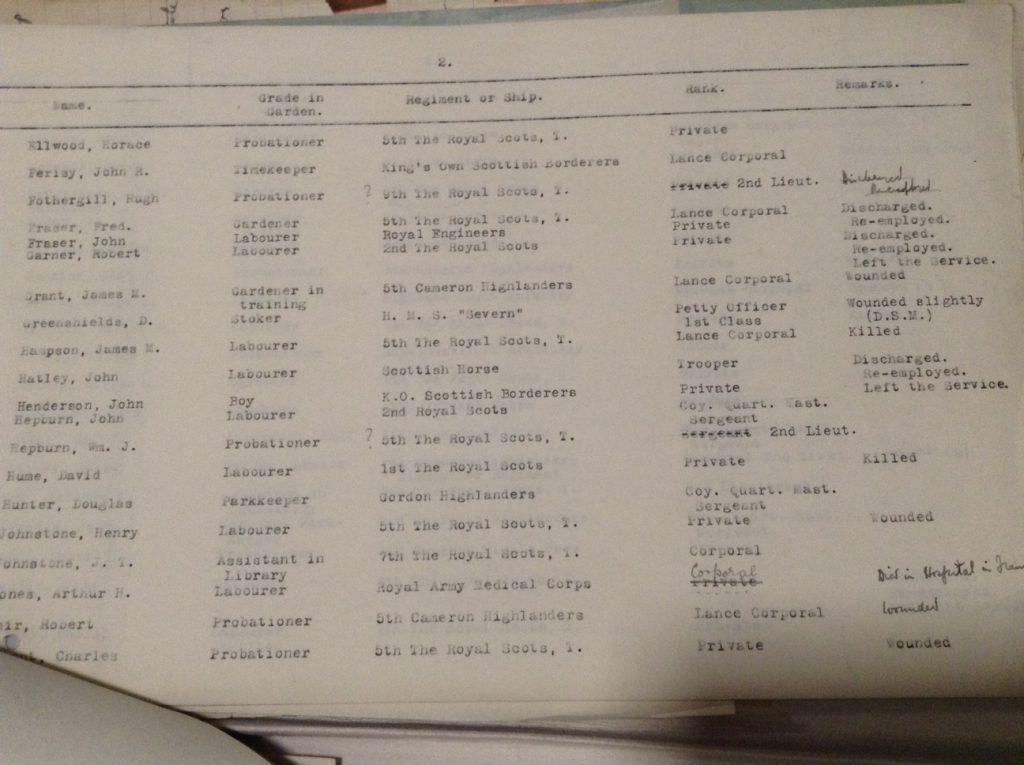

RBGE records state that Hatley enlisted on the 15th November 1914 as a Private, served for 3 years before being killed in action on the 18th April 1918. Another record says he was a Trooper in the Scottish Horse, was discharged and then re-employed. This is at odds somewhat with official Army records available on Ancestry.com, and, as no Hatley killed in April 1918 can be found in the Army records, and the address that we have in the RBGE records, 7 Church Place, is the same address given for the Hatley we were able to find using Army records, we’ll use these for Hatley’s remembrance, and disregard much of our information at RBGE, though why they are different I cannot say. Accurately recording this sort of material must have been near impossible at the time.

I love the details we can sometimes find in the Army Service records where they still exist (many were lost in the WW2 Blitz); in Hatley’s we can see that he was 5ft 9¼ inches tall and had tattoos including a snake on his right arm and flies on the base of his thumbs. His eyes were grey and he had brown hair. He had three older brothers and a sister. We can see that John Hatley enlisted with the 1st Scottish Horse on the 26th August 1914 (this regiment ties in with RBGE records) but was discharged in September due to him being medically unfit to serve. He enlists again on the 8th December 1914, this time to the 16th Royal Scots. The brother closest to him in age (albeit around nine years older) seems to have enlisted with him on the same day as there is a Francis Hatley listed next to him in the Royal Scots medal roles, their service numbers one digit apart. We know Francis survived the war, but is in hospital in 1921, so it may be that he didn’t manage it unscathed.

After enlisting with the 16th Royal Scots, Hatley spent just over a year travelling to various barracks across the U.K. to complete his training. He seems to have had other things on his mind as he is reprimanded and punished (usually by being confined to barracks, a minor punishment) over and over again for leaving the barracks without permission, usually between 9:30 and around 10:30 at night. It was the name of one of the men doling out one of the punishments that alerted me to the significance of the unit that Hatley had joined – Col. Sir George McCrae. Hatley had joined ‘McCrae’s Battalion’, one of the new battalions created by Lord Kitchener in the first months of the war. McCrae’s Battalion was the first ‘footballers’ battalion’, as it was largely composed of footballers and sportsmen, encouraged to enlist by a burgeoning sentiment that the playing of sport could wait until the more important duty of winning the war was undertaken. Perhaps Hatley, already discharged for being medically unfit, and his older brother in his mid-forties, were whipped up into trying again by the fever surrounding the charismatic George McCrae who encouraged hundreds to enlist with an inspired publicity drive which included rallies, speeches, marches and a recruiting station placed strategically close to Heart of Midlothian’s football ground. On Monday 8th December 1914, the day Hatley enlisted, McCrae had recruited 1,120 volunteers who officially became known as the 16th (Service) Royal Scots Battalion, but the men preferred to be known as ‘McCrae’s’. On 12th December, McCrae declared recruiting closed and ordered the Battalion to mobilise three days later (‘McCrae’s Battalion’, J. Alexander, p.86).

After spending just over a year in Britain training, Hatley enters the theatre of War in Europe on the 8th January 1916. He is wounded in the field on the 14th July 1916, the day the 16th Royal Scots assaulted Bazentin Ridge during the Battle of the Somme. On the 20th December he is admitted to the Field Hospital with a sprained ankle received whilst carrying a load along a paved road. He spends some time at a rest station before rejoining his unit on the 10th January 1917.

The Battalion are beginning to prepare for the next major offensive at this point. Their training and drilling was continual as they marched towards the town of Arras. When they reached it in March, it felt to them as if the hard work was just beginning with some arguing that although a rest was what they needed, what they got instead was more drilling and plenty of digging. Trenches and tunnels were being dug from which to launch the attack which eventually happened on the 9th April, a day after Easter Sunday.

The British Army was responsible for a 14 mile stretch of the front line and McCrae’s Battalion were just to the north of Arras, aiming for a high grassy ridge upon which sat the ruins of Point du Jour farm. The plan was to heavily bombard the German trenches for weeks before the attack with the bombardment increasing to a firestorm for the final four days. The men were then to cross No Man’s Land taking the trenches one by one following a timed schedule meaning that each one could be bombed before the men arrived to capture it. At 4:30am on the 9th April the men began to line up in the trenches dug to launch the attack. It was pitch dark, freezing cold and raining and they found their positions with difficulty. Soon the bombardment began and it defied description – it could be heard and felt in the south of England. The men went over the top at 5:30 precisely and made swift progress, apparently crossing the first three enemy trenches in ten minutes. They soon advanced ahead of schedule meaning many were caught in the timed barrages.

McCrae’s Battalion along with other units in the 34th Division took the trench referred to as ‘Blue Trench’ at 7:15am at which point they were to pause to consolidate and allow the 15th Royal Scots to leapfrog through and continue to attack onwards towards the ridge. It sounds as if all of this was plain sailing, but all around the men shells from both sides were crashing down, and there was plenty of resistance left in the German trenches – they were continually exposed to machine gun fire both from ahead and behind. Field Marshall Haig considered the day a success however, writing in a letter to King George V:

“Your Majesty will be pleased to hear that I found the troops everywhere in the most splendid spirits and looking the picture of health. The marching and the joy of operating in the open at last and above all, the fact that the Army was advancing made everyone happy!… The change to open warfare has especially benefitted the Australians: indeed they seem 50 per cent more efficient now than when they were in the trenches…

I am writing this… while the Battle for Vimy Ridge etc. is going on. Everyone is so busy today that I have managed to get a leisure hour for writing a letter! I came here last night so as to be near the HQs of Generals Horne and Allenby [Allenby was in charge of the section Hatley was fighting in]…

The attack was launched at 5:30am, and has progressed most satisfactorily. Indeed, at the time of writing (3pm) the several lines have been captured according to the timetable and a large number of prisoners have been taken; probably 10,000 when all are counted! Our success is already the largest obtained on this front in one day.” (Douglas Haig: War Diaries and Letters 1914-1918, p.278)

The first day of the offensive at Arras could be considered a success. The Army did make significant advances that day, planes in the sky were now being used to spy on the opposing troops and the bombardments were becoming more efficient at cutting through barbed wire rather than just blowing it up into the air. The commanding officers were learning from mistakes made during previous battles, but there was still a long way to go. Tanks were now in use but they were slow, attracted enemy fire and being in them was like sitting in furnace that could explode at any minute. Beyond the land taken was the Hindenburg Line, the new system of fortified trenches that the Germans had been working on for the last seven months – all this lay ahead for the battle weary Allies.

The Arras Memorial at Faubourg-d’Amiens Cemetery, Pas-de-Calais, France. Photo by the War Graves Photographic Project, www.twgpp.org

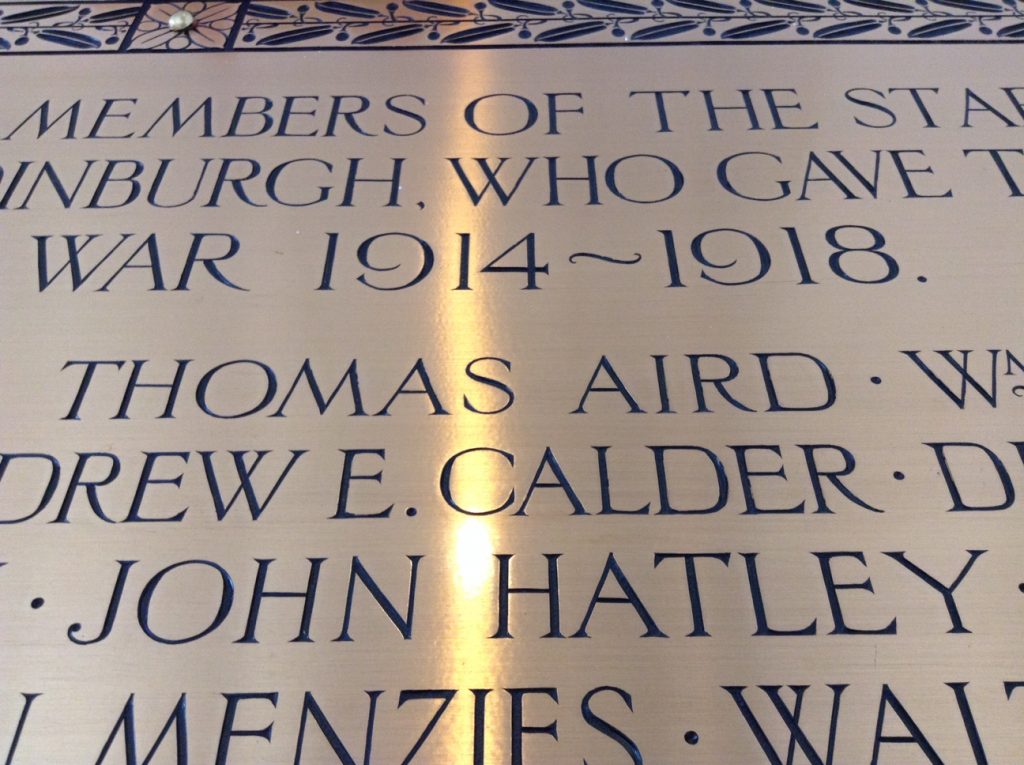

Arras was a reasonably quick battle. After the quick progress of the first day lay another 38 days of slogging it out that we can compare to the 141 days of the Battle of the Somme that had preceded it. Total casualty numbers were therefore lower: 159,000 at Arras, 415,000 at the Somme. If you look at the daily death rate though, 4,076 at Arras, 2,943 at the Somme, it can be appreciated that of all the offensive battles launched by the Allies during World War One, Arras was by far the most lethal (‘Cheerful Sacrifice‘, Nicholls, pp.210-1). It also saw the highest concentration of Scottish troops involved in any WW1 campaign with 18,000 Scottish deaths recorded (BBC News). Amongst those was Private John Hatley. He was noted as being missing when the roll call was made on the return to Arras by the McCrae’s. Eventually he was “accepted for official purposes as having died on or since” the 9th of April, the first day of the battle. His body was never recovered, but he is remembered on the Arras Memorial at Pas-de-Calais, France, and on the memorial in the reception at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

My thanks again go to Garry Ketchen for allowing me to use his genealogical research in this series of blogs, and to Steve Rogers at the War Graves Photographic Project, for allowing me to use their image of the Arras Memorial.

References

Jack Alexander, “McCrae’s Battalion: The Story of the 16th Royal Scots”, 2004, Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh

Jonathan Nicholls, “Cheerful Sacrifice: The Battle of Arras, 1917”, 2010, Pen and Sword Books, Barnsley

Gary Sheffield and John Bourne (eds.), “Douglas Haig: War Diaries and Letters 1914-1918”, 2005, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London

Army Service records available at Ancestry.com