Walking along the path at the foot of the Chinese Hillside last week I noticed that recent clearing has exposed some interesting plants from among the previously impenetrable thicket. Among them I was surprised, so early in the season and despite the recent snow, to see a plant of Prinsepia utilis in full flower. This is an untidy shrub of the family Rosaceae, leafless at this time of year, with green, spiny stems and short racemes of cream flowers. It is widespread in the Sino-Himalaya from Pakistan in the west, to Sichuan in the east, and this collection was made by David Paterson in 2005 in Sichuan (Acc. No. 2005.1436). The species was first described by John Forbes Royle in 1834 and dedicated to his friend James Prinsep, its epithet referring to a useful oil expressed from its seeds. Prinsep was a member of a remarkable intellectual and artistic family who served with distinction in India over several generations. One of James’s brothers, William, arranged for a set of Bengali raga mala paintings, sent by his former business partner Dwarkanath Tagore as a gift for Edinburgh Town Council (as thanks for Tagore’s Freedom of the City), to be presented to Edinburgh University. When Hugh Cleghorn was in the Punjab in the 1860s he was friendly with Edward Augustus Prinsep, a great nephew of James. Edward’s wife Margaret Eleanor, a cousin of Alexander Hunter, founder of the Madras School of Art, drew pine cones for Cleghorn.

Having studied architectural drawing with Auguste Pugin and then chemistry, James Prinsep went to India where he ended up as Assay Master of the Calcutta Mint. He was an outstanding scholar: Royle most greatly appreciated his role as secretary of the Asiatic Society and his revival and editing of the Society’s journal, but also Prinsep’s work on meteorology that fed into his own interest in plant geography. However, it was Prinsep’s 1837 triumph of the deciphering of the elusive, third-century BC Brahmi script that remains one of the most astonishing tales of persistence and scholarship in the annals of Indian history. The identification and dating of the great Mauryan emperor Ashoka that resulted added to the European-led restitution of the crucial role that Buddhism had played in Indian history. Another major figure in this process, following the expunging of the historical record by Hindu fundamentalists, was Francis Buchanan (as a result of his visits to Burma, Nepal and northern Bengal). The tragedy for Prinsep was that the strain of the effort broke his health – he just made it back to Britain where he died in Belgrave Square in 1840 at the age of only 41.

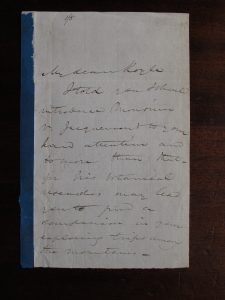

Regrettably Royle has never been the subject of detailed biographical study. From his post as superintendent of the Saharunpur Botanic Garden in the 1820s he undertook major work on Himalayan botany and developed interests in medical and economic botany (cotton and fibre crops), including historical aspects thereof. After his return to London he became professor of Materia Medica at King’s College, and the East India Company’s economic botanist. In 1851 he organised the Indian ‘raw products’ at the Great Exhibition, assisted by Cleghorn. Writing a biography of Royle would, however, be severely hampered as it appears that his incoming correspondence was sold and dispersed. Several years ago I found a few remnants in the possession of a London manuscript dealer, including a plant description by J.P. Rottler, last of the Tranquebar Missionaries. Most thrilling of all were three small documents in the hand of the great James Prinsep – an excised signature, a fragment of a letter about illustrations for the Journal of the Asiatic Society, and a complete letter of introduction that links Prinsep with two major figures in Indian botanical history – the equally effervescent Victor Jacquemont and the more stolid (or, as Joseph Hooker denoted him, ‘flatulent’) Royle:

My dear Royle,

I told you I should introduce Monsieur V. Jacquemont to your kind attention and to more than that – for his botanical researches may lead you to find a companion in your exploring trips among the mountains – I have no need to tell you what to shew him – none know so well how to passer le temps as we the disciples of la belle science!

Ever yours sincy. J. Prinsep. 5th Jany. 1830.

Before ascending the Himalaya and spending time in Kashmir, Jacquemont did visit Royle at Saharunpur, though he was no more impressed by the garden than he was to be of ‘le jardin soi-disant botanique’ at Dapuri that he would visit shortly before his own death, which took place near Bombay in 1832 and, at the age of 31, ten years less than poor Prinsep would achieve.