As a life-long lover of insects, I jumped at the opportunity to volunteer at the Microsulpture exhibition at the Inverleith House Gallery at the Botanics . I had moved home to Edinburgh in May and was looking for something useful and interesting to do and being a Gallery Assistant for Microsulpture was perfect and so I applied. It has been an absolute pleasure and privilege to be in that role, hearing the expressions of ‘wow’, ‘awesome’, ‘spectacular’ etc, being able to answer questions about the exhibition, and give the visitors snippets of information about the photographs, and insects in general. You don’t need to be an expert to be a Gallery Assistant volunteer, as everyone is given information about an exhibition, and each person brings their own background and enthusiasm.

All the gallery volunteers have their own reasons for enjoying the role. For me, RBGE has always been one of my favourite places in Edinburgh, I appreciate art and had often visited the Inverleith House Gallery when in Edinburgh, and this exhibition particularly excited me. As I have already said, I have always loved insects. I studied biology at Edinburgh University, and then went on to carry out research on vision in flies for several years. Even when I switched career path to libraries and archives, insects featured, initially at the library of the Zoological Society of London at London Zoo where the Invertebrate House was one of my favourite places to visit, and then at the BBC Natural History Unit archive of film, video, and sound recordings. I ended up managing the NHU archive for over 20 years.

So what else have I found in my role as volunteer Gallery Assistant in the Microsculpture exhibition?

Sometimes visitors want to share their enthusiasm about the exhibition with someone and the Gallery Assistant is that person! Sometimes, they have their own stories about insects to share or they seek to identify an insect they’ve seen or photographed (with my knowledge I’ve usually been some help). I’ve had some interesting discussions including about the drastic reduction in insect numbers and species numbers in this current time, which many scientists have identified as a 6th mass extinction in the world’s history – this one produced by human activities through climate change, habitat destruction, pesticide use, and pollution.

As an extra, I’ve also been giving short talks about insect vision. It has been a great opportunity for me to share a bit more information about insects and how amazing they are. I couldn’t ask for better visual aids that the incredibly detailed images in the exhibition! It’s been lovely for me to go back to the biology I studied and some of the research I carried out many years ago, as well finding out some new things.

My main focus is on the marmalade fly, a species of hoverfly. As a flying insect, a good visual system is particularly important to it. But I also take the opportunity to point out a few of the interesting features in other species in the exhibition. At the end I ask if anyone has any questions and there are often one or two people who do, which is great.

The talks are only about 6 minutes long, but cover the importance of eyes in the marmalade fly and many other insects. I speak about the structure of compound eyes and the ocelli (simple eyes) and include how eyes can differ between males and females of the same species in eye structure and associated nervous system. It’s useful to explain how insect eyes differ from our own, including how insects see colours differently from us. Especially as we’re in the Botanics, I mention that some of the markings on flowers which help to guide potential pollinators can only be seen in the UV part of the spectrum we can’t see. Insects don’t see red, so their colour vision is best described as ‘different’ rather than ‘better’. I give some examples of how eyes have evolved for particular purposes. It’s a bit of a whistle-stop tour of insect vision, but hopefully it gives a useful taste!

My talks are on all the days I’m on duty and so usually Tuesdays and Saturdays at 2.30 and 4.00, if you would like to hear one.

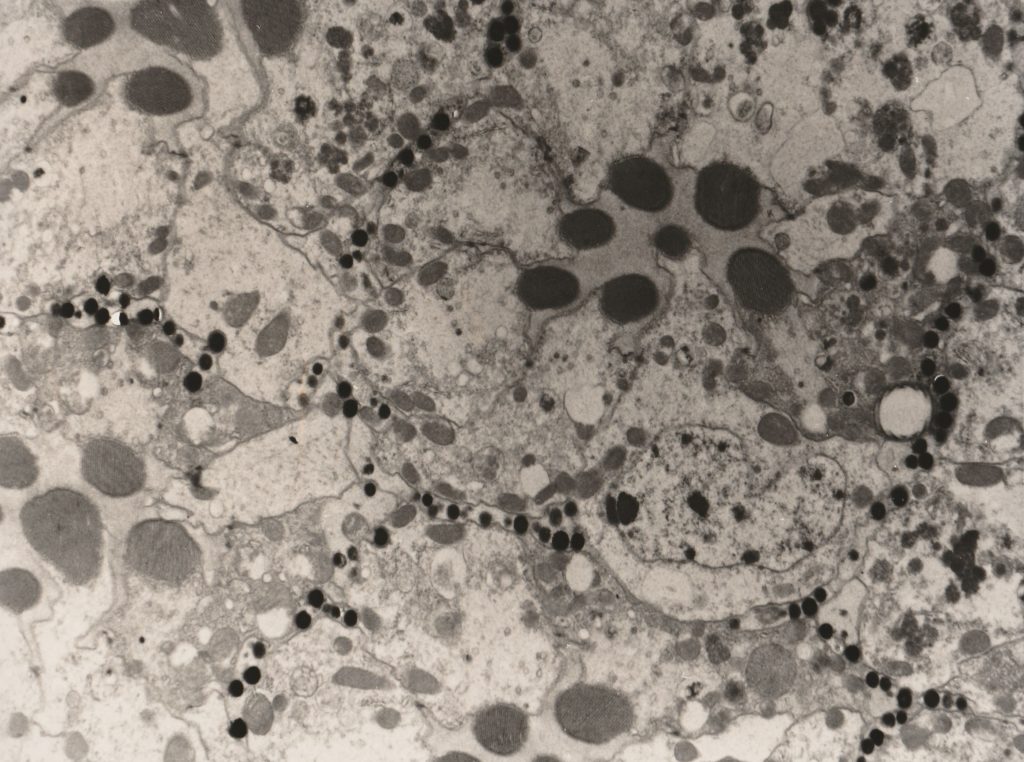

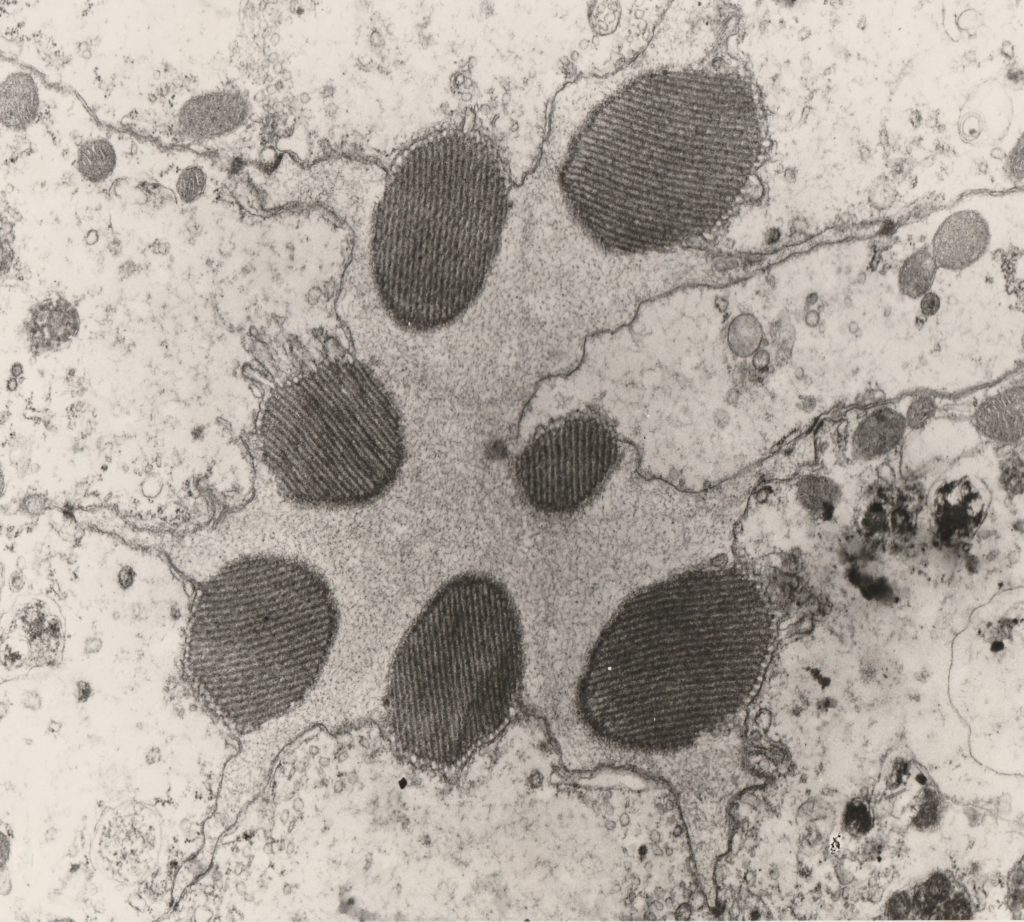

In my talks, I only very briefly touch on the internal structure of the compound eye, and so for Botanic Stories, as a little extra, I’ve looked out a couple of electron microscope photographs taken from my old research work. These are cross-sections of the eye of the tsetse fly (Glossina morsitans) showing the arrangement of light sensitive nerve cells (rhabomeres) in each unit (ommatidium) of the compound eye. You have to imagine that the rhabdomeres are long rods and the images are a slice through them. There is a ring of six with one in the middle. The ‘rods’ in the middle are actually a bit shorter and there are two, one being arranged on top of the other, giving a total of eight light sensitive cells in each unit of the compound eye. The central rhabdomeres are particularly involved in colour perception. In the first image you can see dark spots between the ommatidia which are granules of pigment separating them from their neighbours, so each is more purely looking at one point in space. In the more detailed image you can see the laminated appearance of the rhabdomeres, which are structured to maximise their sensitivity to light.

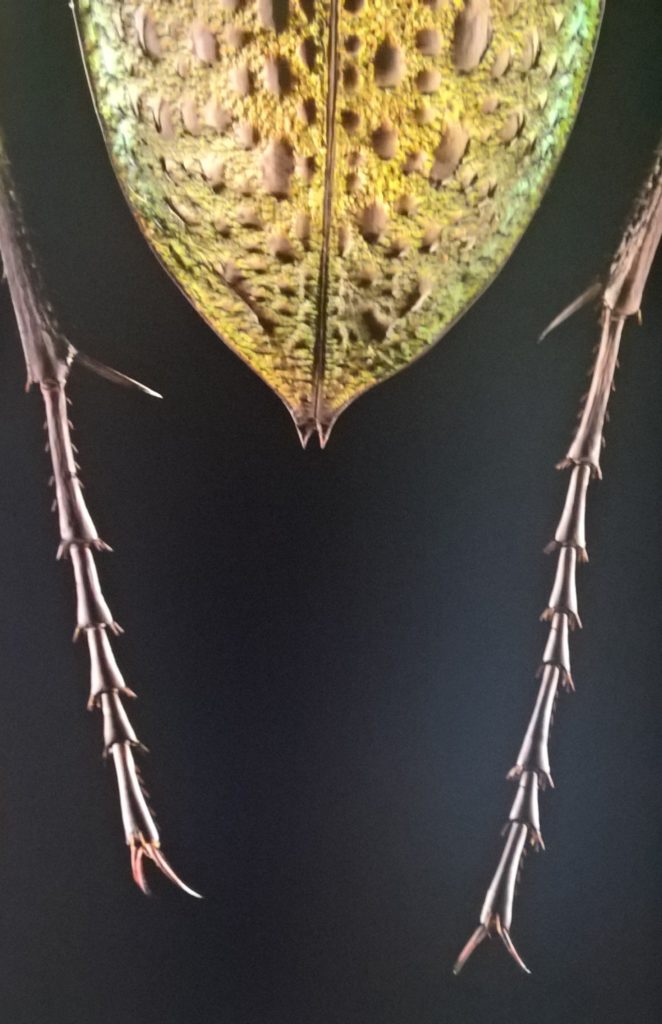

Spending lots of time with the Microsculpture images often means seeing details and features not spotted before. One eagle-eyed volunteer noticed that one hind leg in one of the insects shown had more segments than its counterpart on the other side. The legs are perfectly normal otherwise and so I presume that this is some sort of developmental anomaly in this individual insect.

In giving my talks I’ve come across several other people for whom hoverflies are among their favourite animals. See also guest Botanic Stories author Ashleigh Whiffin’s article. Many people have remarked how the amazing Microsculpture images have helped them to appreciate insects better. They certainly give an excellent taste of the wonder and diversity of insects. You definitely don’t have to be an entomologist to appreciate them, but I certainly have enjoyed being with these creations of Levon Biss. The exhibition has been extended to 10th November which gives more people time to see it – or visit it again!

For more information on Microsculpture visit here

For more information on volunteering as a Gallery Assistant, visit here