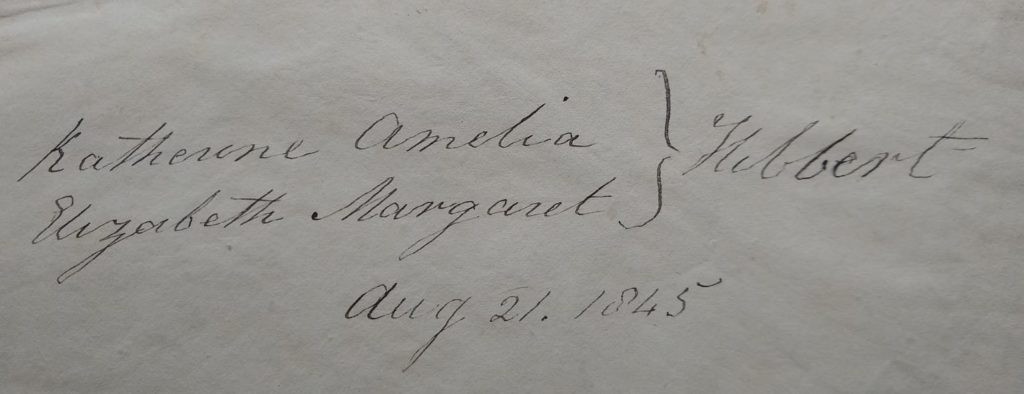

Some years ago, as part of the barter economy, I acquired a handsome, but all but empty, early nineteenth-century album, its calf spine lettered in gilt ‘CHINESE PAINTINGS’. The binding is a luxurious one, of small-folio size, with marbled boards and olive-green, watered-silk endpapers. Tipped onto its flyleaf is a later, supplementary sheet signed with the names Katherine Amelia and Elizabeth Margaret Hibbert and the date 21 August 1845. When I received the album it still contained a loose sheet with a manuscript list of the Canton botanical drawings it had once housed, but the drawings themselves had long since been excised leaving only the stumps of their backing sheets. This list I restored to the current owner of some of the drawings, not only for its record of the original scope of the collection but, more importantly, because it was dated (1778) and it is rare to be able to put a precise date on such Chinese export works.

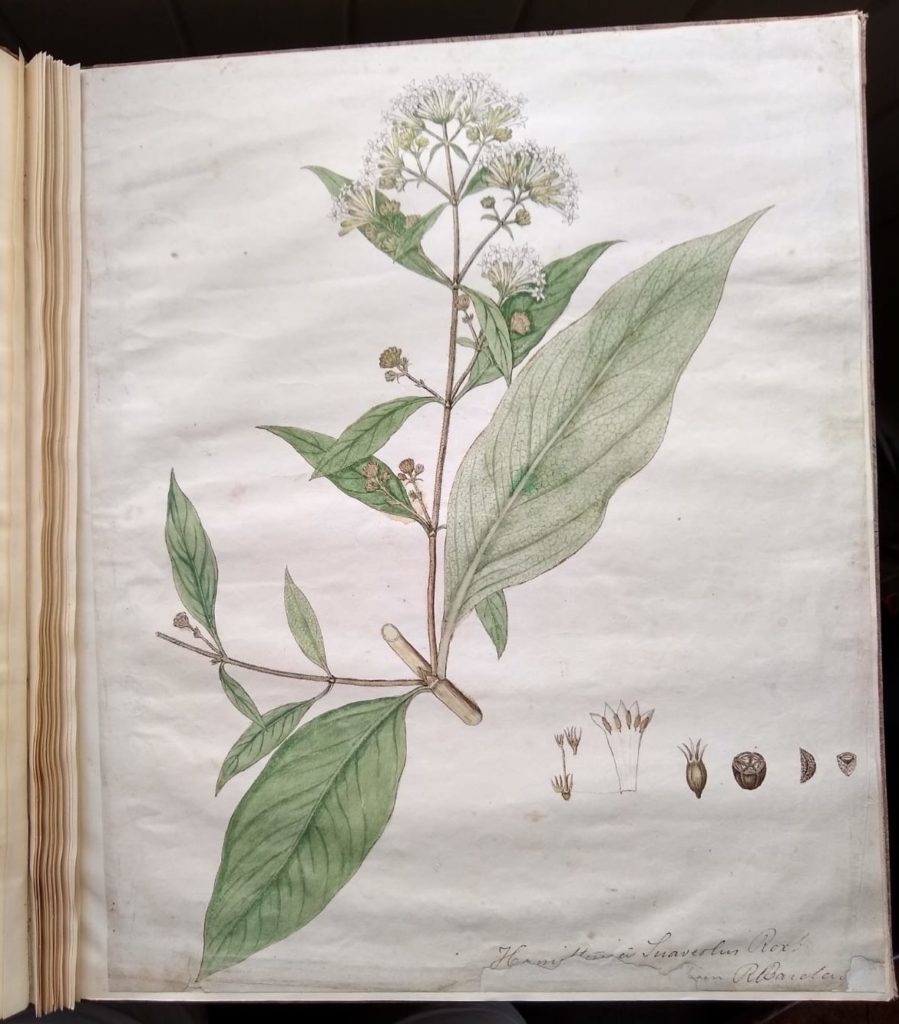

The Chinese botanical drawings weren’t of particular interest to me; the reason for the gift lay elsewhere. A single botanical drawing had survived the carnage – one of primarily scientific rather than artistic interest. Unrelated to them, it originated in India and from about four decades later and depicts the plant ‘Hamiltonia suaveolens Roxb.’ With it, on a separate, folded leaf, is a contemporary manuscript description of the plant including the etymology of the generic name. The drawing is a copy of one of the Roxburgh Icones, of the sort made in the Calcutta Botanic Garden in the later 1810s or ’20s during the tenure of the original commissioner’s indirect successor Nathaniel Wallich. The manuscript is a copy of Roxburgh’s description of the plant, which was eventually published in his posthumous Flora Indica, and also bears a key to the floral dissections shown in the drawing. The drawing had clearly been damaged before being stuck into the album, with part of its lower margin missing. What remains reads: ‘…. [fr]om R. Barclay’. Enigmatic though this appears, it opens up a remarkable series of connections across three continents – between Calcutta (William Roxburgh and Nathaniel Wallich), Philadelphia (the Hamilton and Barclay families) and Clapham, London (Robert Barclay and the Hibbert family).

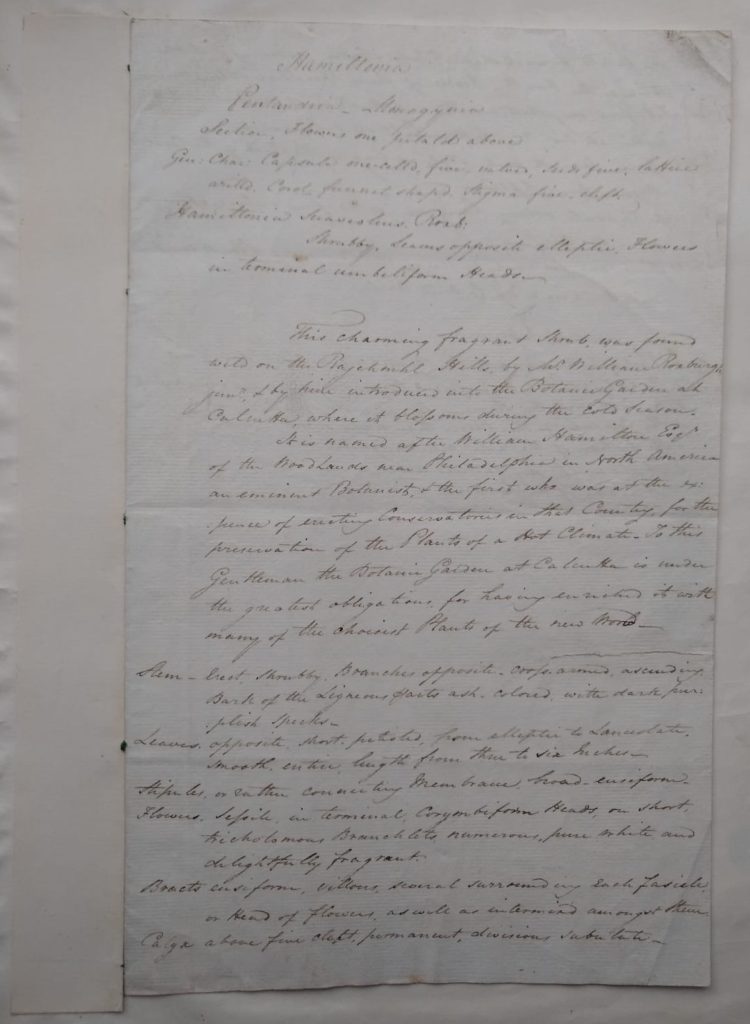

In the two decades that William Roxburgh was Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanic Garden (1793–1813) he increased the number of plants grown from 300 to 3500, achieved by means of a network of collectors and correspondents, nationally and internationally, including two of his own sons. One of the most generous correspondent-donors was William Hamilton (1745–1813) of Philadelphia, who pursued horticultural activities on his estate of Woodlands (the Neo-Classical mansion survives; its grounds were turned into a cemetery in 1840). No fewer than 176 introductions between 1796 and 1810 are credited to Hamilton in Hortus Bengalensis. On a plant-hunting trip in the Rajmahal Hills in 1801 Roxburgh’s 21-year old son William found an attractive member of the family Rubiaceae that he sent back to Calcutta. His father realised that it represented a new genus and species to which he gave the name Hamiltonia suaveolens, not realising that Willdenow had already used the generic name as a replacement for a North American genus (Hamiltonia oleifera Willd., an illegitimate replacement for Pyrularia puber Michx.). The first publication of the binomial was in 1814 in Roxburgh’s Hortus Bengalensis but as there was no accompanying description it was not validly published and would, in any case, have been ‘illegitimate’ as a ‘later homonym’. Although Roxburgh published little botanical work himself he did, during his 40-year Indian career, assemble a large corpus of plant descriptions, 2500 of them accompanied by a botanical drawing by an Indian artist known collectively as the ‘Roxburgh Icones’. Of these one set was kept by himself (these are still in the Botanic Garden in Kolkata) and a duplicate set sent to East India House in London (now at RBG Kew). The original drawing of Hamiltonia suaveolens must have been made between 1801 and 1813 by a member of what was, by then, a small team of artists based at the Garden. The accompanying plant descriptions, which formed a manuscript ‘Flora Indica’, also existed in several copies, one of which was left in Calcutta with his friend the Rev. William Carey when Roxburgh departed from India in 1813. Carey was himself a keen botanist and, through the vehicle of the Serampore Mission Press, a prolific publisher. On return to London Roxburgh’s own Flora Indica manuscript was submitted to Robert Brown (Sir Joseph Banks’s librarian), who sat on it. Nathaniel Wallich, Roxburgh’s indirect successor, did somewhat better and started to publish the work at Serampore, but at snail’s pace because of the not unreasonable desire to augment it with his own additions and discoveries. Only two parts of this edition came out, in 1820 and 1824. Roxburgh’s original description of Hamiltonia, with its dedication to:

Mr William Hamilton of the Wood-lands near Philadelphia in North America, an eminent botanist, and the first who was at the expense of erecting a conservatory in that country for the preservation of the plants of a hot climate … [to whom] the botanic garden at Calcutta is under the greatest obligation for having enriched it with many of the choicest plants of the New World

was published in the latter volume but had, in fact, been pre-empted in London. Realising the value of Roxburgh’s drawings Banks had, in 1795, started to publish a selection of them, the images redrawn, engraved and hand-coloured, on lavish imperial-folio scale, as the Plants of the Coast of Coromandel. The text was initially edited by Banks’s librarian Jonas Dryander, but Dryander died in 1810. In the tenth part (as plate 236, published in May 1815) the drawing of the new Rubiaceae was published, but placed in a new genus, Spermadyction, doubtless because the editor (by this date probably Robert Brown) was aware of Willdenow’s earlier use of the name Hamiltonia. Because there is no indication of authorship other than Roxburgh’s on the title page, both the new genus and the binomial must be attributed to him as Spermadyction suaveolens Roxb., which remains the plant’s accepted name (the genus remains monospecific). The new generic name must, in fact, have been coined by Brown, to whose authorship it is attributed in an article on the plant that he published in Edwards’ Botanical Register in 1819.

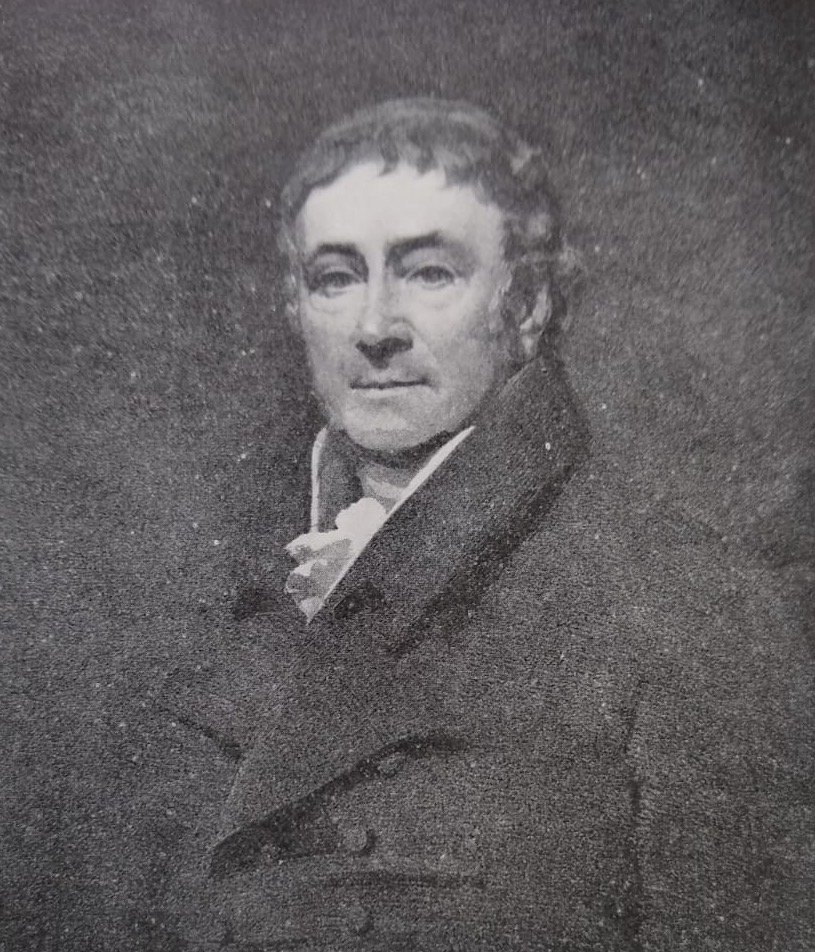

So much for the pre-history, what of the version of the drawing in the Hibbert album? After a period of temporary charge Nathaniel Wallich (1786–1854) succeeded to Roxburgh’s post in 1817. He was something of an outsider in British Calcutta, being a Dane and Jewish, but in 1808, when the Napoleonic wars allowed the temporary British takeover of the Danish settlement of Serampore, Roxburgh, recognising Wallich’s talents, had given him a job at the Botanic Garden. Wallich was touchy, scientifically old-fashioned (a Linnaean), and a crashing snob, but would faithfully continue Roxburgh’s agenda and pursuits at the Garden until his own retirement almost thirty years later in 1846. He continued to employ artists and to use the Garden as a base for the exploration of the S and SE Asian flora using a network of collectors. He had decided, but curiously inconsistent, views on what was Garden property, and it was almost certainly Wallich who was behind the order that, on Francis Buchanan’s departure from India in 1815, he must leave behind the drawings he had commissioned during his survey of Bengal. Buchanan blamed this order on the Governor-General, the Earl of Moira (shortly to become Marquess of Hastings), but Moira was on tour in Upper India at the time and surely had more important matters, such as the Gorkha War, on his mind. Wallich had also stopped another temporary holder of the Superintendent’s post, James Hare, from having copies of the Roxburgh Icones made, for which Hare had obtained permission from Moira/Hastings, whose personal physician he was. And yet! Wallich did have copies of some of the drawings made, some for sending back to the EIC, others, such as this one of Hamiltonia, most probably as personal gifts in a ploy to further the Garden’s interests. And when, in 1828, Wallich travelled on furlough to Britain, he took the entire collection of the drawings he had commissioned (about 1200), and the vast herbarium he had amassed, back to Britain where he left them (and hence the accusation of inconsistency), leaving only the Roxburgh Icones at the Garden. Wallich was an assiduous cultivator, by correspondence, of rich and aristocratic British garden owners, sending exotics for their conservatories in return for additions to the Calcutta Garden.

One such wealthy British garden owner was Robert Barclay (1751–1830). Barclay came of an old Aberdeenshire Quaker family, one branch of which crossed the Atlantic and established itself in Philadelphia where its members must undoubtedly have known another family of high net worth with Scottish roots, the Hamiltons. Robert was born there in 1751 but sent back to school in London where, in 1781, he purchased the Anchor Brewery, Southwark, from Dr Johnson’s friend, the recently widowed Hester Thrale. This he developed, as Barclay, Perkins & Co., and it made him a fortune. In 1781 he bought a large house on the north side of Clapham Common, just to the west of the parish church of Holy Trinity (focus of the Clapham Sect). The house, which still stands, was called ‘The Elms’ (it was later home to the architect Sir Charles Barry) and appears to have remained in the family, though from 1805 Barclay himself spent most of his time at Bury Hill near Dorking, which he purchased in 1815 having initially rented it. At Bury Hill Barclay devoted himself to gardening. On the other side of the world, in 1826, following the first Burmese War, Wallich visited Burma. At Pegu he discovered a new genus of waterlily, which he dedicated to ‘my highly respected friend [italics added: at this date they can never have met] Robert Barclay, Esq. of Bury Hill, a most worthy benefactor to the science of Botany’. Wallich’s description of Barclaya longifolia was in the form of a letter to H.T. Colebrooke who read it to the Linnean Society in 1827. While once in the Kew library Wallich’s extensive correspondence was ‘repatriated’ in the early twentieth century to Calcutta, where it has suffered gravely from the ravages of insects and humidity. In it does, however, survive a letter that reveals the connection with Barclay. It was written by Barclay from Bury Hill in December 1828, while Wallich was on leave in London, and concerns a subscription to Plantae Asiaticae Rariores, the magnificent work published by Wallich during his furlough. Like its exemplar, the Plants of the Coast of Coromandel, its three volumes include 300 superb, hand-coloured plates in imperial folio, but these were reproduced by the then new technology of lithography. In the absence of written evidence nothing can be proved, but it seems likely either that Barclay asked Wallich for a copy of the drawing of the plant named for a family friend from Philadelphia days, or that, realising the link, Wallich sent him it as an unsolicited gift.

It is Barclay’s house on Clapham Common that makes a link with the Hibbert family, and a suggestion as to how the drawing might have ended up in their album. An 1800 map of Clapham shows that next door to The Elms was a similarly large mansion belonging to George Hibbert (1757–1837). Also arboriculturally named this house was ‘The Hollies’, the suburban base (he also had a house in Portland Place) where Hibbert had his garden and, with the help of his gardener Joseph Knight, specialised in the cultivation of Cape and Australian plants. Hibbert was another merchant prince, but with dramatically different political views to those of the best known of his Clapham neighbours. His wealth was based on the West Indian trade and slave plantations and he was the founding chairman of the West India Dock Company. In 1798, in an attack on an anti-slavery motion proposed by his neighbour on the west side of the common, William Wilberforce, Hibbert made a passionate speech on the financial benefits of the slave trade. It is therefore rather extraordinary to think of him living next door to the Quaker Barclays, let alone of their being on swapping-of-botanical-drawings terms. Nevertheless, given the location of the Calcutta drawing, Barclay clearly did give it to a member of the Hibbert family. The most likely recipient was George Hibbert himself and that the album was originally his. The Chinese drawings fit well with his horticultural interests, as does the fine binding – he was known as a bibliophile and the owner of a notable library (which included a Gütenberg Bible). There is, however, a more specific possibility as Hibbert ended up being the purchaser of collections made in China by James Main in 1793–4. Main returned to London after a three-year trip only to discover that his sponsor Gilbert Slater had died, and Slater’s executor had sold the collections of drawings, seeds and plants to Hibbert. Most of Hibbert’s library was sold in 1829 (for £23,000) when he moved from London to his wife’s family property of Munden Hall, Hertfordshire. Perhaps the album of pretty botanical drawings was kept back for his grand-daughters, though at his death in 1837 they were only infants – Katherine Amelia 5 and Elizabeth Margaret 3. Eight years later, when the sisters added their names to the album, they would be 13 and 11 respectively. The sisters’ father Nathaniel trained as a lawyer but had no need to practise; their mother Emily was a daughter of the Rev. Sydney Smith. Katherine remained unmarried (and was still alive at Munden the time of the 1861 Census); Elizabeth married the Tory politician Henry Thurstan Holland, who was later (after her early death, aged 21 in 1855) created Viscount Knutsford.

A postscript on two Robert Barclays: Robert Barclay (1758–1816), banker of The Elms; Robert Barclay (1751–1830), brewer and botanist of Bury Hill.

I am grateful to Charles Barclay of New Zealand for pointing out that two Robert Barclays have been conflated in the foregoing. In this I followed a statement by Ernest Nelmes in an article on the botanical Robert Barclay of Bury Hill (to whom William Hooker dedicated volume 54 of the Botanical Magazine in 1827) who seems to have made the same mistake. Nelmes wrote that in 1781 this Barclay went to live in Clapham and developed a garden.

The story is complicated because the two Roberts were close contemporaries, who must have known each other well: they shared a paternal grandfather David, who married twice. Alexander, the son from David’s first marriage, went to Philadelphia, where he must have known the Hamiltons, but sent his son Robert to London as a boy to be brought up by his half-uncle David, a son of the grandfather’s second marriage. David had an elder brother John whose son Robert Barclay (1758–1816) became a banker, and it was he who owned The Elms at Clapham. The two Roberts were therefore half-cousins. It seems almost certain (from the Philadelphia connection) that the ‘R. Barclay’ noted on the Hamiltonia drawing is the botanical Bury Hill one, so perhaps he gave it to the Hibberts while visiting his namesake and cousin next door.

Charles Barclay

Confusion of Robert Barclays, plural:

You seem to be confusing and confounding two quite separate (but related) Roberts….

Robert Barclay “of Clapham”. 1758-1816 – Banker.

Built & resided at The Elms, Clapham

Robert Barclay “of Bury Hill”. 1751-1830 – Brewer

Born Philadelphia…. Leased/purchased Bury Hill in mid-life.

See pedigrees viii & xx….

Part 1 of 3

A history of the Barclay family,

with full pedigree from 1066 to 1924

Compiled by Charles W Barclay.

Full text archive facsimile, u.s. library scanned (downloaded DEC2020) at:

https://archive.org/details/historyofbarclay00barc/mode/1up