Making biodiversity data accessible and discoverable.

With a background in taxonomy, phylogenetics, and biodiversity informatics, Professor Rod Page’s current work focuses on making biodiversity information accessible and discoverable. He regularly posts opinions on the state of the field on his “iPhylo” blog. A former chair of the Science Committee of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), he helped GBIF move from awarding prizes to researchers for past work to having an annual “challenge” to encourage innovation in the use, analysis, and visualisation of biodiversity data.

Making the biodiversity literature accessible

Much of Rod’s work is in collaboration with the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL). “The BHL is the largest open-access library of biodiversity literature, both old and new,” says Rod, “and is a fantastic resource for retrieving species descriptions, as well as ecological observations spanning two to three centuries.” For example, researchers in Australia wanting to assess the effects of recent wildfires on plant distributions are turning to BHL to find published records of species prior to the fires.

“However,” Rod explains, “much of the BHL is organised as scanned volumes rather than the individual journal articles that modern researchers expect.” His BioStor project locates articles within BHL and makes them easier to find. To date, some 230,000 articles on taxonomy, ecology, and distribution have been identified.

Visualising biodiversity data

“Biodiversity data readily lends itself to visualisation,” says Rod, “such as the maps of millions of specimen records produced by GBIF.” He has a long-standing interest in evolutionary trees, and is exploring ways to visualise trees together with other sources of biodiversity data. For instance, DNA-barcoding – a new technology by which species can be identified based on small stretches of DNA – is having a major impact on our ability to measure and monitor biodiversity, yet this data is poorly integrated with other types of data. In a recent project, Rod combined phylogenetic trees, taxonomy, and maps in a single visualisation. He hopes to expand on this pilot project to be able to provide new ways for biodiversity scientists to navigate through millions of DNA sequences.

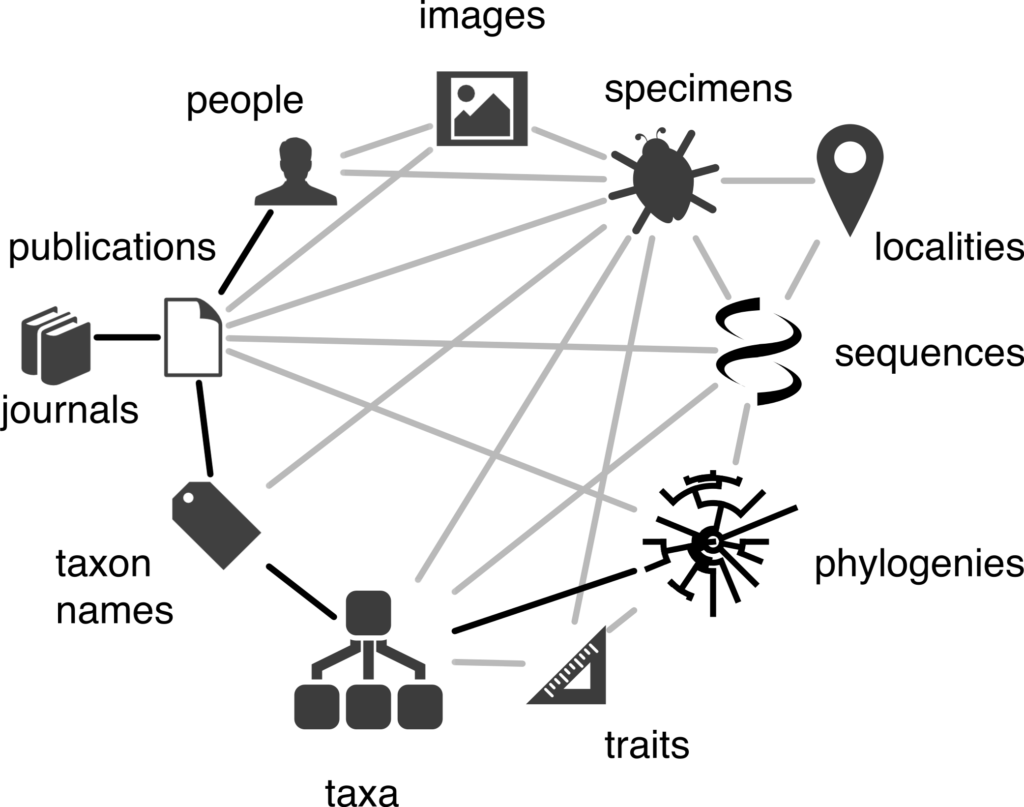

Linking biodiversity data together

One feature of the biodiversity informatics landscape is the sheer number of different databases (each with its own acronym), with content ranging from taxonomic names, museum and herbarium specimens, citizen science observations, species distributions, DNA sequences, scientific articles, trait data, and more. “Many of these databases are essentially data ‘silos,,” says Rod, “lacking direct connections to other databases.” For instance, it can be challenging to trace the connections from a DNA sequence to the ‘voucher’ specimen from which it was taken, to the museum housing that specimen, to the species the specimen represents, to the original taxonomic research that discovered the species, to the people involved in that research! Linking all these things together would give us a ‘biodiversity knowledge graph’ – an interconnected network of biodiversity information. Rod is exploring ways to assemble this graph, in particular whether Wikidata – a data-focussed relative of Wikipedia – can be the basis for this knowledge graph.

The importance of agency in science

Much of Rod’s work centres around computers, code, and data. “One feature which makes working with computers attractive is that they give you ‘agency’ – the ability to create new things (such as new databases or web sites),” he explains. “If a database you want doesn’t exist, you may well be able to make it. If an existing database doesn’t do what you want (e.g., BHL not having articles, GBIF not showing evolutionary trees) then you might be able to build that feature yourself.”

This degree of agency can be exhilarating, and has parallels in the rise of citizen platforms such as iNaturalist, where readily available technology (phone cameras, apps, and a website) has led to a vibrant community generating millions of observations. “There are many challenges facing biodiversity, but access to information should not be one of them,” Rod concludes.

Rod Page is Professor of Taxonomy at the University of Glasgow. Find out more here.

This post is part of a series showcasing Scotland’s innovative, high-impact research supporting biodiversity conservation, in partnership with Scottish Government and NatureScot. Read the rest of the series here.

Further reading

Page, R.D.M. 2011. Extracting scientific articles from a large digital archive: BioStor and the Biodiversity Heritage Library. BMC Bioinformatics 12(1): 187. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-187

Page, R.D.M. 2016. Towards a biodiversity knowledge graph. Research Ideas and Outcomes 2: e8767. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.2.e8767

Page, R.D.M. 2019. Ozymandias: A biodiversity knowledge graph. PeerJ 7: e6739. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6739

Page, R.D.M. 2020. An interactive DNA barcode browser. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4266482

Groom, Q., et al. 2020. People are essential to linking biodiversity data. Database 2020: baaa072. https://doi.org/10.1093/database/baaa072

Page, R.D.M. 2022. Wikidata and the bibliography of life. PeerJ 10: e13712. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13712