The marsh saxifrage (Saxifraga hirculus) is a golden jewel of our bogs and marshlands. Each small plant bears one or two flowers, bright golden yellow and often dotted with orange markings on the petals. You could be forgiven for thinking it was a buttercup but the tell-tale red hairs on the stems of are a helpful guide.

Growing in mossy beds in bogs and flushes, it is a plant that needs irrigation by lime-rich water from springs. The flow provides oxygenated water to the roots. The requirements of water chemistry, temperature and flow go some way to explaining its rarity. The mosses that grow alongside need the same conditions and create a miniature world for this jewel, often on a slight gradient surrounding a spring.

The main reason that marsh saxifrage is considered threatened in Britain is because drainage of bogs for agricultural production and forestry has virtually eliminated the species from its former lowland sites. In Scotland it is now restricted to seven sites and genetic studies have shown that the populations contain limited genetic diversity. Reproduction is often by vegetative spread forming clonal patches. This means that the number of genetically distinct individuals is often much lower than the number of physically distinct patches.

The isolation of the of surviving populations from each other means that they cannot interbreed. This prevents the genetic mixing needed to counteract the negative effects of inbreeding. Greater diversity may also give the species a better chance when adapting to challenges, such as climate change. This is where the Scottish Plant Recovery project enters the story with the aim of turning the tide for this threatened plant.

The big challenge is keeping the marsh saxifrage alive in cultivation long enough for seed production. A new generation of plants, grown from the seeds, can then be returned to appropriate sites. To achieve this has involved being innovative as nobody has kept this demanding species alive for any length of time. The limit seems to be about two years. By working hard to deliver what this plant needs we are learning things that will be useful in the ongoing conservation effort. This is what the practice of conservation horticulture does. If we succeed, we will also boost numbers and diversity in the surviving wild populations.

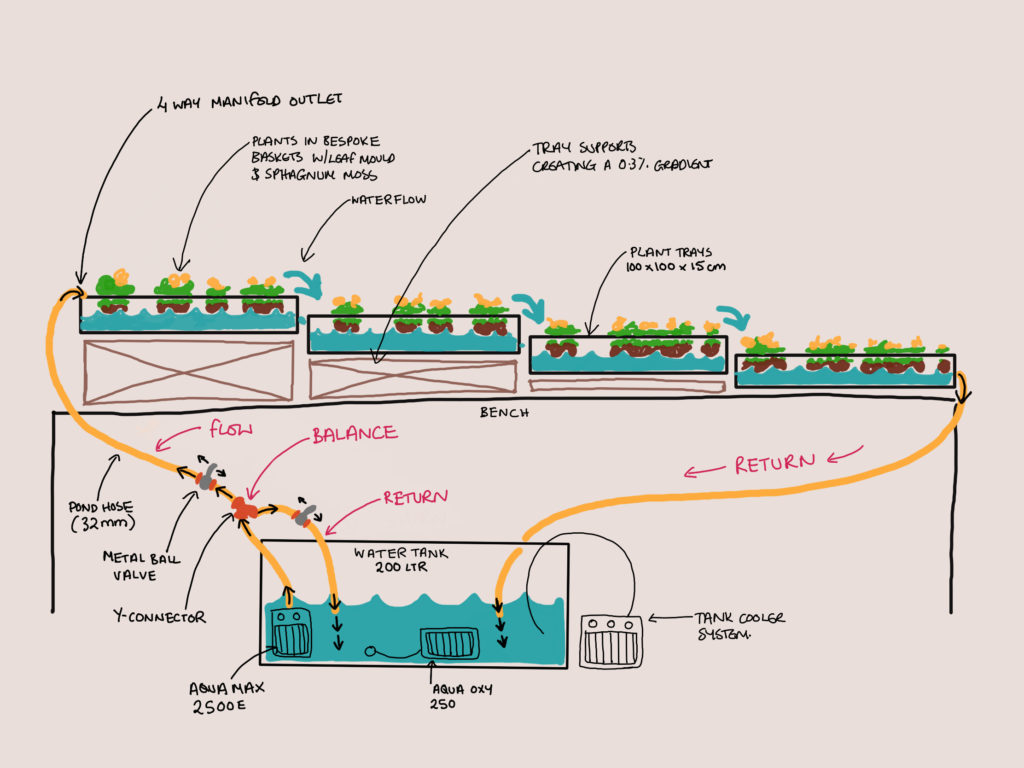

So, when the team ordered a beer chiller a few eyebrows were raised. But this is not for summer refreshment, it is at the heart of a construction, christened the ‘cascade’, in the Garden’s nursery. A stepped sequence of large plastic trays allows water to flow, under gravity, as it is pumped from the cooled reservoir at the bottom back to the tray at the top. It is the cascade of water from tray to tray that maintains the oxygen level.

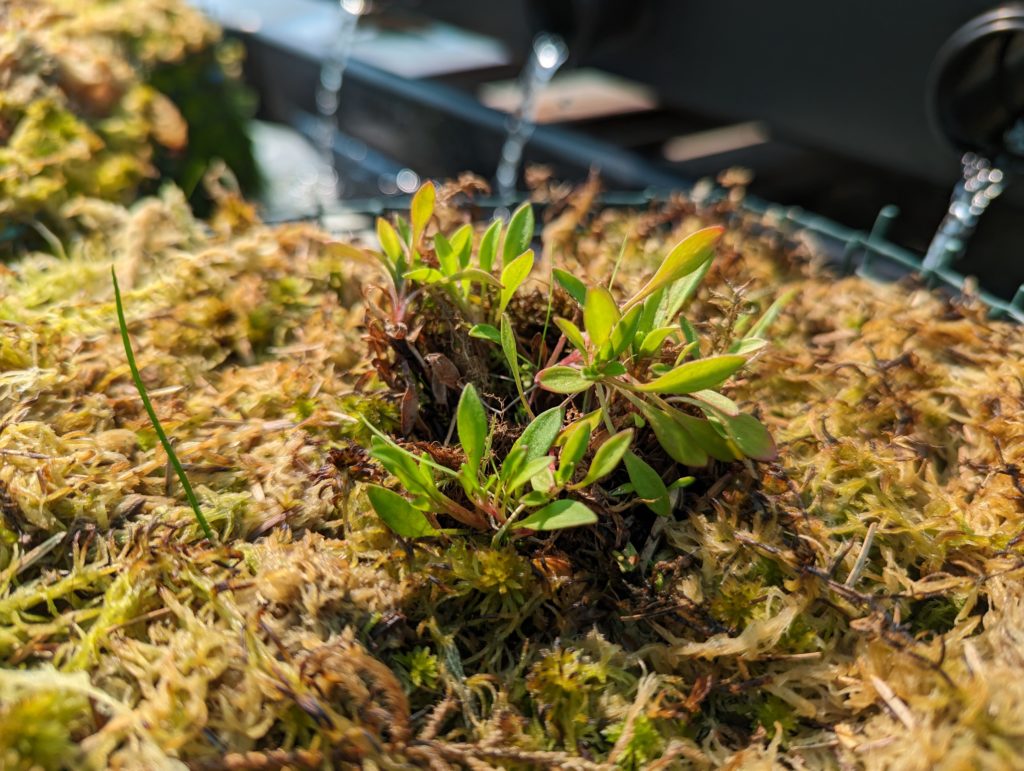

The precious plants are in baskets of moss that have been designed to ensure that the root remains 14cm above the water table, the average measurement taken from observations of wild populations. Baskets are filled with sphagnum moss, which filters metals from the water. Within the centre of these sphagnum cubes is a mix of leaf mould and coir, replicating as close as possible the properties of peat. Finally, the baskets are topped with sphagnum, providing moisture by capillary action from the bottom and sides.

When planted up, these baskets are placed in the trays and the temperature and pH are regularly monitored to ensure that the life support system is providing the conditions needed. The initial set up involves 15 trays, and this will double by the second year of the project. Translocations back into the wild are planned for year three.

So far, results are looking promising. The plants removed from the wild in a small plug of the surrounding vegetation have come into growth and look healthy. Some plants have recently begun to flower, and controlled cross-pollination has been carried out as a trial. Most of the pollination will be allowed to happen naturally as the shade tunnel is open to flying insects.

Plants are also being grown from seed collected outside Scotland to increase the genetic diversity. There is already a robust set of plants of Russian origin grown from tiny seeds in early 2023. The signs are looking good that we can give this beautiful and rare Scottish plant a boost in several of its few remaining wild localities.

Post written jointly by Rebecca Drew and Max Coleman.

- Twitter @TheBotanics

- Twitter @nature_scot

- Twitter and Facebook @ScotGovNetZero

- Facebook @NatureScot

- #NatureRestorationFund