In a previous post I proposed that the rate of plant species discovery had not significantly changed in the last fifty years despite enormous changes in technology. A comment was made that this might be due to the lack of trained plant taxonomists. I remember when I did my MSc in Plant Taxonomy at Reading University back in the 1980s this was one of the things we were told. At that time Reading was one of the very few places globally where one could take a course dedicated to plant taxonomy and nomenclature.

In response to the comment I said it would be hard to produce figures to show how many working plant taxonomists there were but that my hunch was there were fewer in Europe and North America but more in the megadiverse countries of the global South.

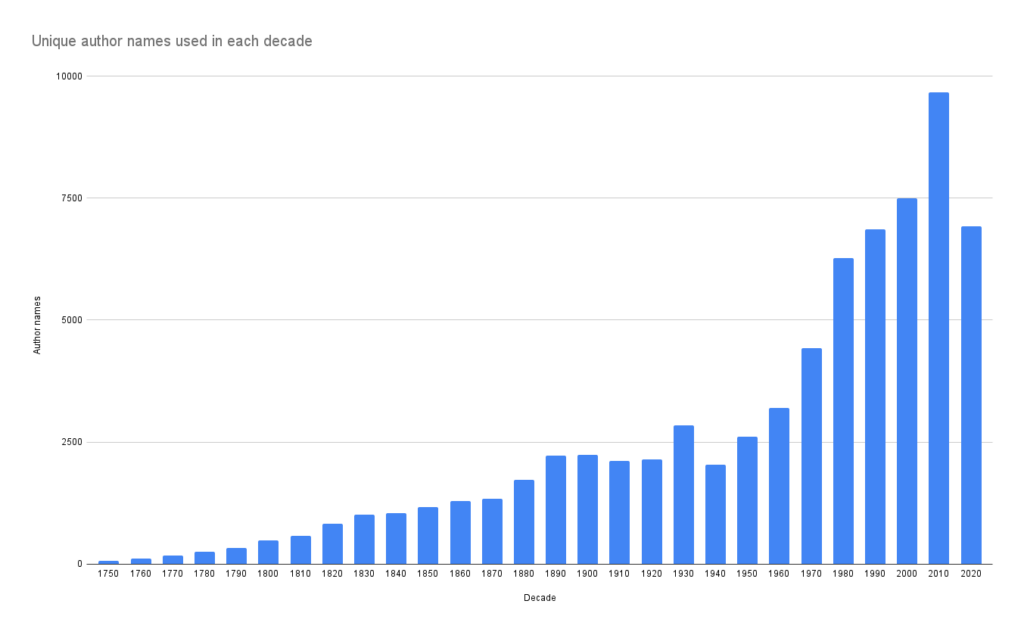

I thought it would be hard to count working taxonomists because I imagined surveying botanical institutes and universities to physically count them. Then it occured to me that this wasn’t necessary. A plant taxonomist is generally someone who publishes new taxa and combinations of taxa so we simply need to count the number of authors per year to get the answer. I wrote a script to run over the 1,638,553 non-deprecated names in the December 2024 release of the WFO Plant list and extract the 38,213 author names that weren’t in parentheses or before an “ex” in the author string and count the unique ones that occur in each decade since 1753 and we get the graph below.

Other than dips around the world wars, and the fact that we are only half way through the 2020s, there has been a steady (exponential?) increase in the number of working plant taxonomists in every decade since Linnaeus. As the final decade isn’t complete we can probably assume that there are around ten thousand working plant taxonomists in the world today.

Reasserting the caveates: This is counting unique names of people who have published new plant names (nom nov or comb nov) in each decade. It will be missing some people where their names are clashing and it hasn’t been caught by the IPNI author names or Wikidata databases. It will be double counting people who change their names (e.g. on marriage). It is defining a plant taxonomist as someone who has published a nomenclatural act within the calendar decade. This is a very narrow definition of a plant taxonomist! An analogy would be counting surgeons rather than medics in general. Surgeons can’t do their work without anaesthetists, radiographers, nurses, pharmacists, family doctors etc. There may be many experts who spend their time identifying plants, collecting specimens and even writing floristic accounts but who do not actually publish new names. The taxonomic community is therefore bigger than indicated here.

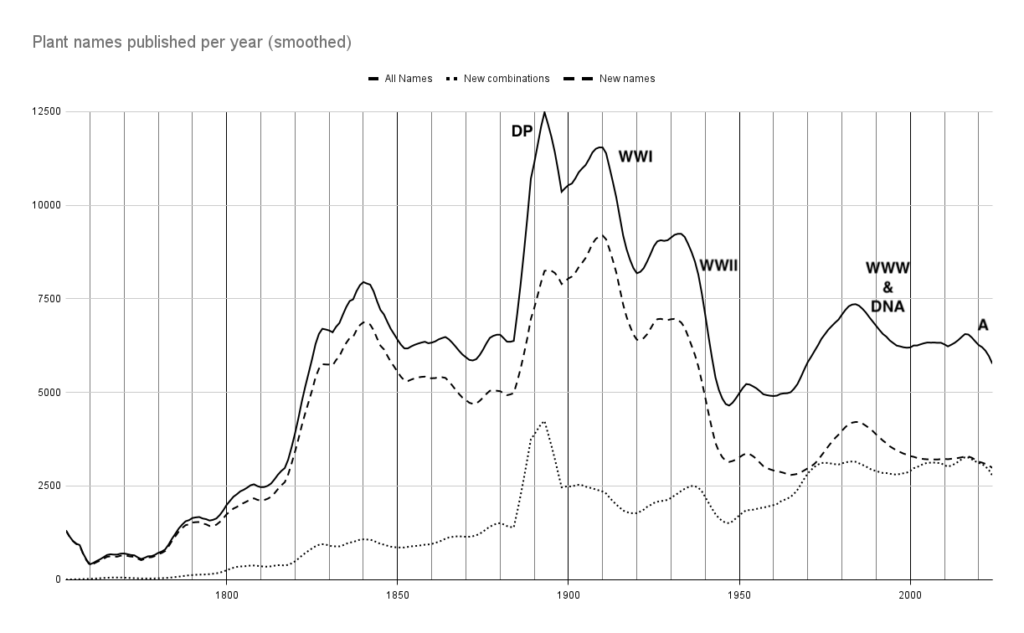

For comparison here is the graph of the number of new names published per year from my previous posts.

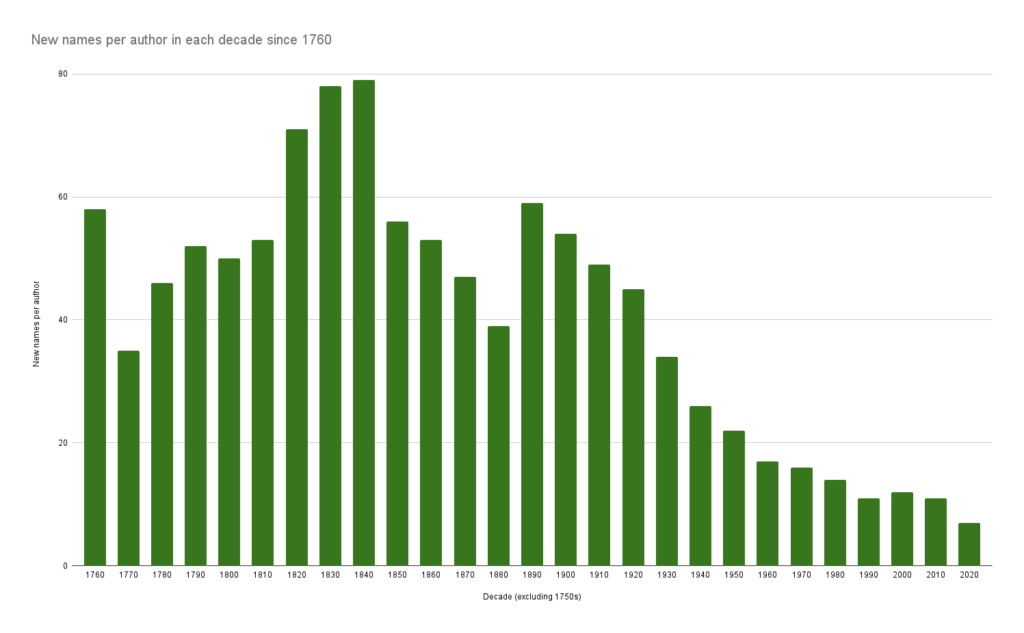

If the number of taxonomists has risen rapidly over the last half century but the number of names published has remained constant the obvious chart to create next is the average productivity per decade. Here it is:

I have excluded the 1750s from this graph. The “average” taxonomist in the decade of Species Plantarum published 148 new names! Nevertheless we are on a 130 year downward trend. That is not necessarily a bad thing and is worth speculating about.

Science has become more rigorous in all fields since the 19th Century. Gone are the days of publishing a new species with a two line diagnosis, although that might still be legal it is no longer common. Today we expect some level of analysis possibly including a molecular phylogeny.

We are describing more cryptic species in more remote and shrinking pockets of biodiversity. We have already picked the low hanging fruit.

As I initially suggested, there has been a big change in the social model of how species are described. In the past plant material would have been passed back to colonial and ex-colonial centres where a few people would actually do the publication of new names. Today that work has moved to a larger, more diverse workforce spread across the world. Jiajia Liu et al (2023) published a very interesting paper that uses a similar approach I have taken here to look at “Who will name new plant species? Temporal change in the origins of taxonomists in China” Their work is based on the POWO dataset managed at RBGE Kew. The names in POWO are near identical to those in the WFO Plant List – we work very closely. Jiajia Liu et al show this movement of descriptive effort to countries with higher biodiversity and make a plea for greater support and recognition of this. I came across their work after I had done the analysis above. It is comforting that the general approach is good enough to have occurred at least twice and made it into a rigorously checked, refereed paper rather than just an opinion piece blog post like this. Please read more in Jiajia Liu et al and the papers cited there.

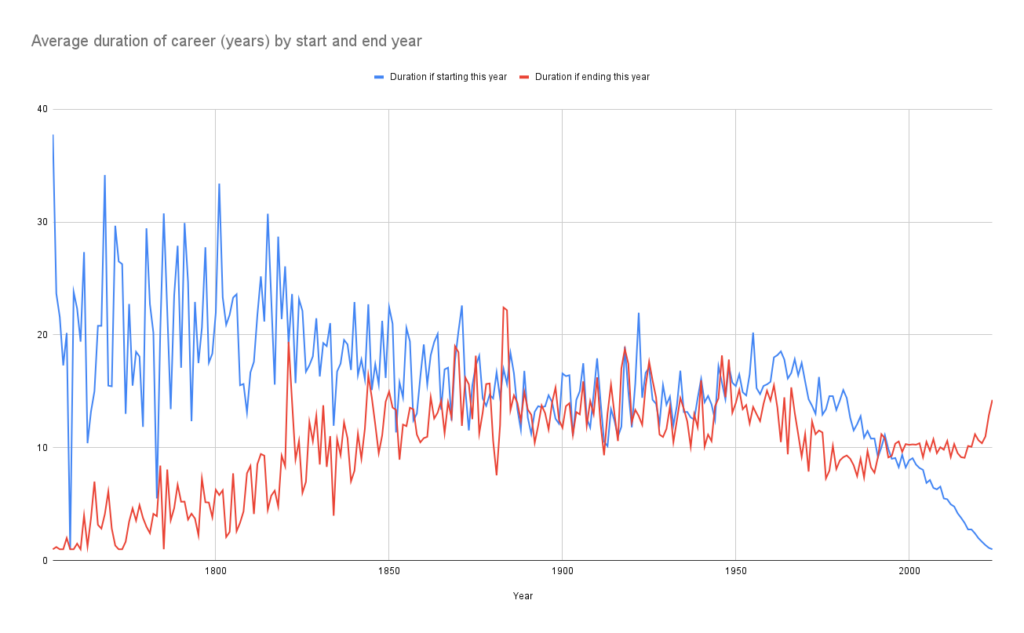

My final piece of speculation is possibly the most tenuous and hardest to test. Have we moved from most names being published by people in stable professions to names often being published by graduate students who go on to do something else as a career? When training new taxonomists it is typical for them to monograph a small group as part of their studies. If they are lucky this may be followed by postdoctoral work on a related group but they have to be very fortunate to then find a post where they spend the majority of their time doing plant taxonomy. Does the graph above really show the rate at which careers in taxonomy are shortening? Individual taxonomists may be as productive now as ever but their taxonomic careers amount to a couple of publications at the culmination of their education. For a final chart I looked at the length of careers of taxonomists by considering the date of the first name they published vs the last name they published. Messy data really catches up with us here! There are 2,343 of the 38,213 (6%) authors that appear to have careers longer than 50 years and a quick look at these showed that many were caused by dirty data – names with the wrong year or wrong author. There will also be use of the wrong name abbreviation in later years and other confounders. To ignore the worst of the outliers I exclude names that appear to be published more than 70 years after the author first published a name but it is still messy.

We obviously expect the duration of careers starting after 2000 to be less than 24 years and the trail off in the blue line is therefore a function of the calculation. But does it start too soon? The average length of a career is between ten and twenty years from 1800 to the 1960s. This is maintained by many short careers and a few very long ones. The flattening out of the red line since the 1990s suggests that the average is no longer being bolstered by longer running careers. People who haven’t published a name since 2010 are unlikely to start publishing them again. On average their careers were only 10 years long.

This final chart, like the rest of this blog post, is just a provocation to set your thoughts running and maybe encourage you to do some analysis of your own. The latest data produced by the WFO Plant List is always available to download from this DOI:10.5281/zenodo.7460141 and we are here to help you, the best we can, with any analysis you might want to run on it.