Trees in general, and wych elms (Ulmus glabra) in particular, are being given a second chance in the dramatic landscape of Assynt. Land owned by both the community and environmental charities now accounts for a significant proportion of land in Coigach and Assynt due to recent land purchases. But these new landowners are finding the relationship with their neighbours, various traditional sporting estates, to be complicated by apparently incompatible objectives. Emotions quickly run high in discussions about changes to favour the return of the woodland that was once abundant in this now predominantly treeless area.

The Garden’s Scottish Plant Recovery team is working with the owners and managers of a large parcel of land at Ledbeg that has been fenced, at considerable expense, to exclude the red deer (Cervus elaphus) that are abundant in the area. ‘Abundant’ doesn’t even begin to convey the sheer numbers of deer on the hills in this part of Scotland. The nickname for the area among some locals is the Serengeti, after the national park in Tanzania that is famous for large herds of grazing animals and their movement in the ‘great migration’. As I drive into the hills around Loch Assynt, I see why the name is appropriate, I’m greeted by several large herds of deer. My visit here is to meet representatives of various organisations, including Culag Community Woodland Trust and the Woodland Trust, to assess some trial elm planting carried out a year ago by the Scottish Plant Recovery team and to look at future opportunities.

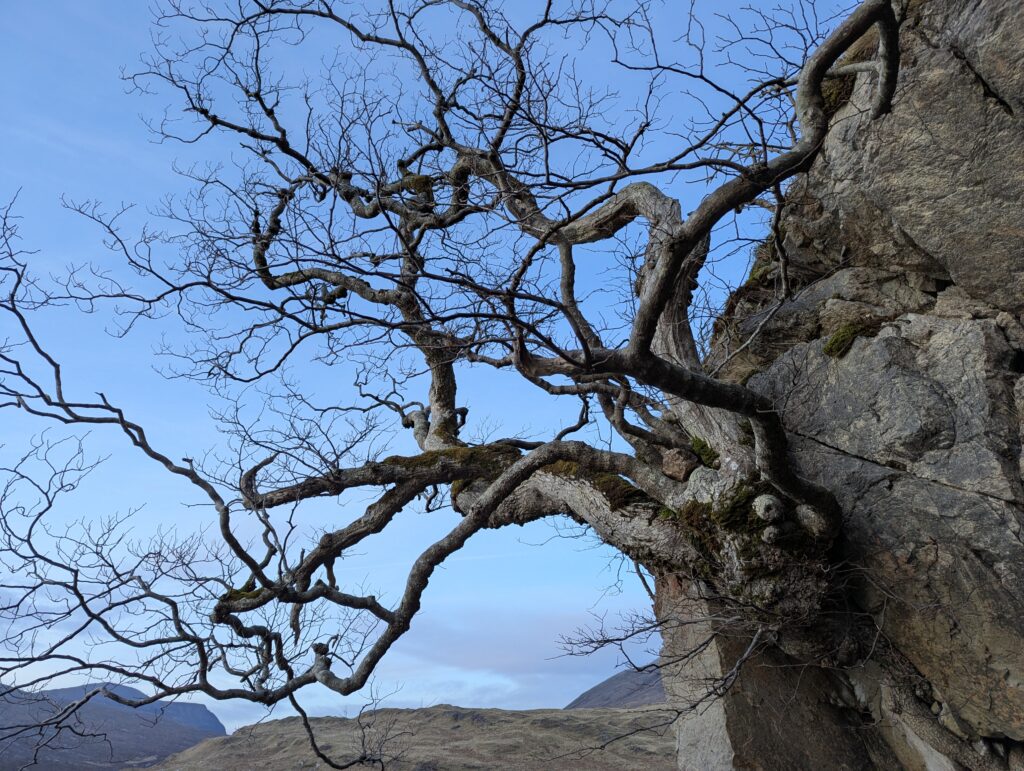

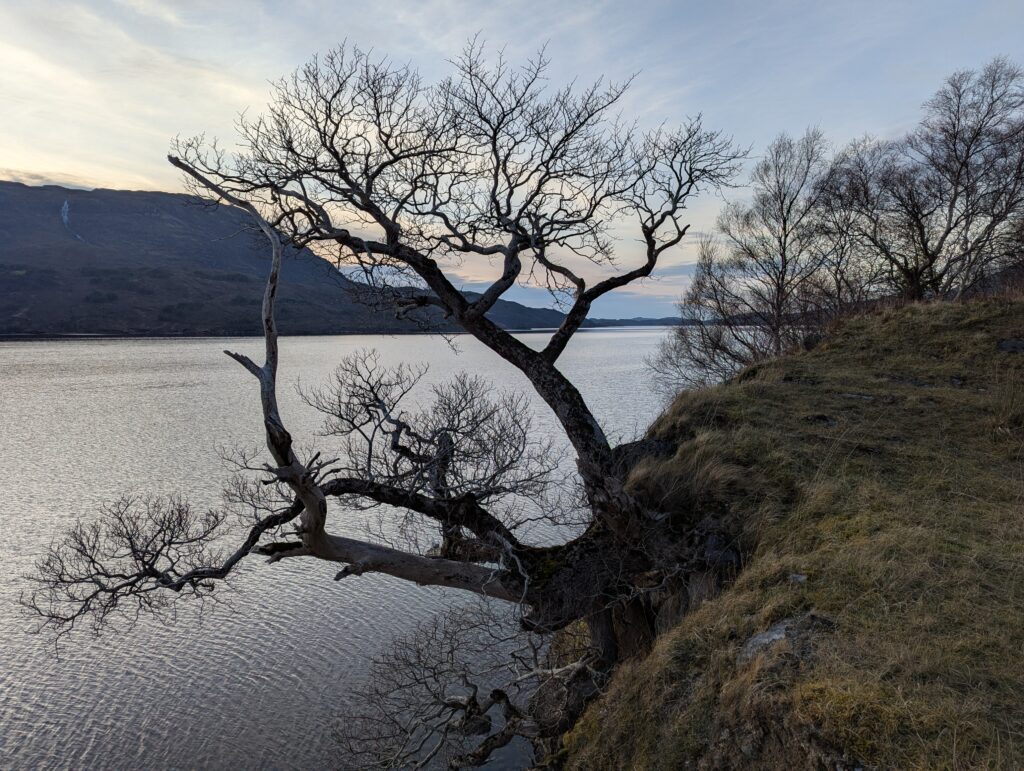

The meeting place is outside the house at Ledbeg that sits beside the Ledbeg River. There is a gentle series of waterfalls at our meeting point and about four mature wych elms cling to the rocky slopes on either side of the falls. One of the trees has become dislodged and is now hanging above the rushing water with little anchorage, yet it is still alive. Chris Puddephatt, a photographer living in the area who is documenting the elms of Assynt, is pleased to be here as these elms have been on his hit list for a while. His catalogue of elm images encompasses at least 90 trees and his online gallery of Assynt’s elms is a remarkable record of survival against the odds. Many of the elms grow from crags that protect them from the deer.

We begin the 15-minute walk to the planting site up a gentle slope and over some quite boggy ground. Elaine Macaskill from the Woodland Trust thinks it should be possible to find someone with a suitable vehicle to get the trees and planting equipment right up to the site. This is good to hear as carrying everything in by hand would be quite a task. As we approach the fenced area herds of deer are visible outside the fence. Elaine explains that the fenced area is so big it has altered the way the deer move through the landscape and has created greater deer browsing pressure in some other nearby areas. Deer fences are unsightly and expensive, and everyone involved would rather not be putting them up. The trouble is that trees will not get away under the current high grazing pressure from deer without fencing or individual tree tubes. For red deer the tubes need to be 1.8 m tall and are expensive and extremely unsightly. For large numbers of trees, a deer fence is the lesser of two evils.

We pass into the site through an enormous gate that is much taller than me and begin to hunt for the 35 elms already planted by the Scottish Plant Recovery team. The first few we locate have vanished without trace, save for the square wooden peg with a black label screwed to it. The label has the unique accession number of each tree. We are aided by a map showing all the planting locations. The mystery of the missing elms is quickly solved as we find more trees showing vole (Myodes glareolus) damage. There may also be some damage from mountain hares (Lepus timidus) as some of it seems too high up for voles. The missing trees were presumably bitten off at ground level.

Despite the bitter wind, the group is enthusiastic to find as many elms as possible and by the end of a good hour of searching we have located 11 healthy trees. Nearly all have been damaged to some extent, but as we work, we reposition vole guards from nearby trees that no longer need them. All these trees should recover. The lesson to take away is that all future planting must include vole guards and the necessary order for biodegradable guards has already been placed as I write this post. We don’t have time to locate every spot where a tree was planted, but our estimate of the losses is that perhaps 25 percent of the trees have been killed by voles or hares.

As we get ready to walk out there is a conversation about the sensitivity of the subject of reducing deer numbers. Sporting estates are valued by how many stags they support, so talking about reducing deer numbers equates to the devaluation of a neighbour’s land. It is easy to understand why this is such an emotive subject. Objective, scientific methods to calculate the carrying capacity of a parcel of land have been developed for red deer. Progress towards a deer density that the land can sustain would be helped by placing value on the quality rather than quantity, in other words deer health rather than number.

Everyone in the group agrees that the next step is to be guided by evidence rather than emotion. We need to know how many deer the land can sustain in a healthy state. The health and welfare of the deer is of greatest concern in winter when food becomes short, and deaths are not uncommon. These are wild animals, and their only food is wild plants. As forage declines the weaker animals succumb. It seems obvious, but the calculation of carrying capacity must take account of the area that is not feeding the deer, such as bare rock and water bodies. Likewise, the nature and productivity of the vegetation must be part of the assessment. This would be a start, and we could at least say what number of deer a given area could comfortably support. It would certainly be a number much smaller than the current historically high density.

To appreciate that wild red deer in the Scottish Highlands today are undernourished you only need to look at the bones of their prehistoric forebears who were significantly larger animals. The red deer is an animal of woodland and in a wooded landscape, with a lower population density, they grow into bigger, healthier animals.

One interesting point that is raised in our conversation is that if anything stalking is becoming more important than ever. We will need to reduce numbers and keep on top of that task to maintain lower numbers, and this will require more trained stalkers. In addition, as the landscape responds with a resurgence of woodland it will become a correspondingly more skilful task to stalk the deer. A new generation of ‘land managers’ is needed who see stalking as a vital part of maintaining a state of balance in the ecosystem. We have removed the apex predators (wolf and lynx) that would control deer numbers naturally, preventing damage from excessive grazing. If we are not willing to bring those predators back, we need to take on the job of properly managing deer numbers ourselves.

As we walk back to our cars it feels like the conversation with all of those who own and manage land in Assynt is going to be hard and progress will feel slow. Romany Garnett, who has worked for conservation organisations in Assynt for many years, tells me that ‘people are quick to say they have the right to continue as they always have, but we also have the right to manage the land differently and in a way that is sensitive to all of nature’.

… people are quick to say they have the right to continue as they always have, but we also have the right to manage the land differently and in a way that is sensitive to all of nature …

Mandy Haggith, freelance writer and elm enthusiast, tells me of her personal connection with elms. As a child growing up in Northumberland, she remembers the time when the elms in a valley near her home were suddenly lost to Dutch elm disease. The exposure of the soil resulted in erosion and landslips and a tranquil place of refuge seemed destroyed. For Mandy the work on recovery of elm in Assynt is giving her hope. She describes how the ‘elm recovery gives a sense of having a second chance to do the right thing’. As a child Mandy felt unable to do anything for the elms. Now she is raising awareness of the importance of Assynt’s elms, a rare survival of mature trees, as Dutch elm disease creeps ever closer. This time around we can plant elms that may stand a better chance against disease. That’s the hope at least. Soon another 200 elms bred from survivors of disease in the Scottish Borders will be making the long journey to Assynt. They will be planted with the first trial group and not far from the wild elms at the falls on the Ledbeg River. But it’s important to remember that this work is not just about elms, or even woodland, it is about the health and future of an entire ecosystem, and that includes the red deer. If the experience at Ledbeg inspires wider landscape change it will also give the deer a second chance to grow to their full potential.

Left to right: Mandy, Romany, Elaine (Woodland Trust), Jane, Max (RBGE) and Chris.

- X @TheBotanics

- X @nature_scot

- X and Facebook @ScotGovNetZero

- Facebook @NatureScot

- #NatureRestorationFund