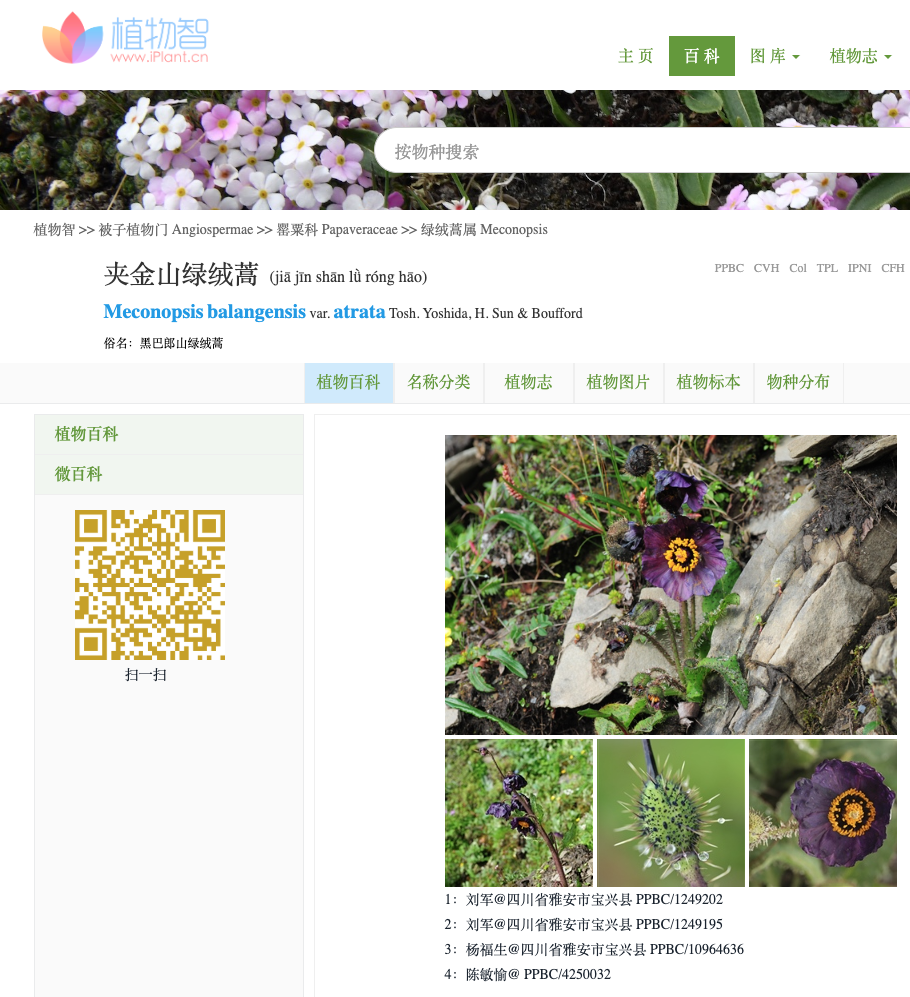

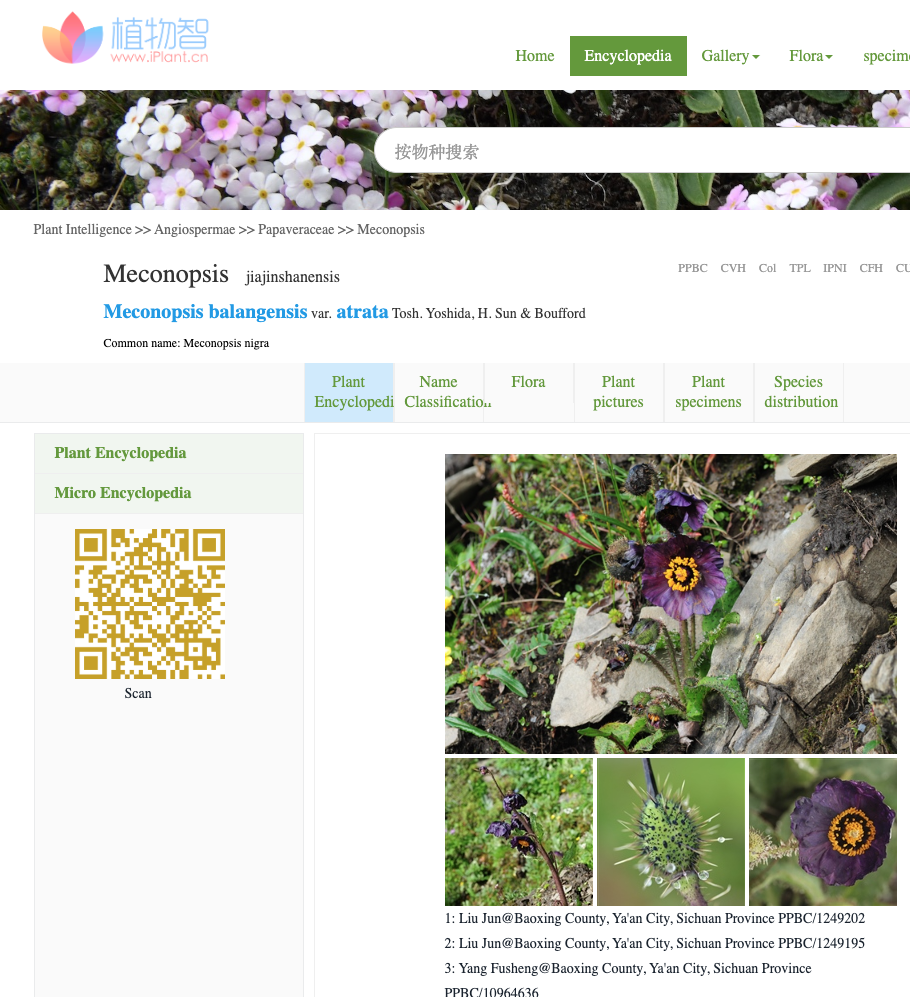

An online discussion about exchanging seeds of a new species called Meconopsis jiajinshanensis led to the Chinese botanical website iplant.cn and the page for Meconopsis balangensis var. atrata.

The automatic translation of this page into English by Google generated the name Meconopsis jiajinshanensis from the Chinese vernacular name. Someone had taken this fictitious, hallucinated name and started using it as a real Latin binomial.

iPlant.cn is doing everything correctly and citing the real scientific name in full. It is the generic translation software causing the issue. A non specialist might argued that the translation algorithm acted correctly in making up a name for the plant in English/Latin. It might be what they would do. But the result is a word that is misleading. Indeed it misled real users who began to propagate it online as if it were a Latin binomial. This got us thinking.

When taxonomists monograph a group of plants they must account for all the names found in the literature. They do this by tracking down the original place of publication for each name. Sometimes names will be found that haven’t been validly published and take a lot of time to sort out. There is no global register of published names so there is always the chance that something appearing to be a scientific name was correctly published but not listed in a public database. Each name needs to be checked carefully. The main sources of erroneous names today are handwritten labels on herbarium specimens or the glitches in optical character recognition (OCR). But this Meconopsis episode looked like something different, a new source of trouble.

We coordinate the World Flora Online Plant List. This is a consensus list of all the vascular plants and bryophytes in the world. Once erroneous names are in circulation they tend to keep coming back and wasting researchers’ time. We call them zombie names. As keepers of a major plant list we can’t just delete them from our database. We need to recognise them when they return so that they don’t suck up more of our time. If someone searches our database we need to warn them to watch out for the zombies. We can feel a little like Tilda Swinton or Adam Driver in the cult movie The Dead Don’t Die – swatting zombies on behalf of an innocent public. Who says nomenclature isn’t cool!

Machine learning (ML) has been in use for many years doing things like helping to focus a camera or improve search results. Recently generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems have become widely available and are increasingly competent at creating text, images and even movies. They are artificial neural networks trained with huge amounts of data to produce a Large Language Model (LLM). LLMs generate content typically in response to text prompts. Sometimes this is referred to as just “guess the next word”. It is argued that the LLMs are Stochastic Parrots – they just repeat what they have heard with a little randomness but without real understanding. Unfortunately this is also a good description of much human behaviour. The LLMs are starting to mimic us very well. In humans, guessing the wrong word is call a mistake. With LLMs creating the wrong output content is called hallucination although there are arguments it would be more correct to call it bullshitting.

When the Google algorithm translated the Chinese page it hallucinated a new word, ‘jiajinshanensis‘. This rang alarm bells for us because it showed that LLMs could produce zombie names. As vast amounts of content is now being generated using LLM based tools there is the potential to produce a zombie apocalypse of new names that could overwhelm our resources.

Adam Driver – The Dead Don’t Die – © Universal Pictures

To explore this a little further we asked ChatGPT (version 3) to give us the scientific names for a list of thirty vernacular names from the BSBI species list for the UK. This was an arbitrary selection of composites. The actual prompt used was: “Please create a table with two columns, one containing the vernacular names given in the list the other column with the correct scientific name.” Followed by the list of names. This resulted in some names that were very obviously made up and so second prompt was given: “Please do that again but don’t make up any names.” The response was “Here’s a table with the vernacular names you provided alongside their corresponding scientific names without making up any names:“. The results were fascinating. They can be broken down into three main categories.

First are the ones that ChatGPT got right. An example is Shoolbred’s Hawkweed the response was “Hieracium shoolbredii”. The LLM did not include author strings in any of the names. The name in the BSBI list is Hieracium shoolbredii E.S.Marshall.

Second are the names where the LLM clearly guessed (hallucinated) but got lucky. An example is Green-leaved Hawkweed. The response was “Hieracium viridiflorum” which means green flowered so is a kind of school child’s guess. The name Hieracium viridiflorum Peter is only found on a handful of herbarium specimens but exists. It is probably a typo of Hieracium viridifolium Peter which is a synonym of Pilosella viridifolia (Peter) Holub. Neither of which have any relation to the BSBI accepted name of Hieracium chlorophyllum Jord. ex Boreau. Wide-stalked Dandelion is another example. It gave “Taraxacum platycarpum”. Again platy- implies flat and wide so it is clearly a guess based on meaning. There is actually a species called Taraxacum platycarpum Dahlst. but it is endemic to Japan and Korea and unlikely to have an English common name. The BSBI accepted name is Taraxacum euryphyllum (Dahlst.) Hjelt. These lucky guesses maybe a product of the arbitrary way the list was chosen. It represents genera with many thousands of species epithets and so just taking a guess and not including an author string is likely to hit an existing name.

The third category are the names that are clearly entirely fictional. Beacons Hawkweed gave “Hieracium beaconsense”, an attempted Latinisation of Beacons that isn’t done correctly and has never existed. The correct answer is Hieracium breconicola P.D.Sell. The same thing happened with Ormes Head Hawkweed which came back as “Hieracium ormesense” which doesn’t exist. The correct name is Hieracium britanniciforme Pugsley. Acute-leaved Dandelion was “Taraxacum acutifolium” (it is amazing nobody has published that name already considering the number of epithets published in Taraxacum) which is actually Taraxacum acutifrons Markl.. The acme was “Hieracium fleshy-leaved” returned for Fleshy-leaved Hawkweed. The LLM has obviously given up on even attempting to Latinise the vernacular name at this point! The correct name is Hieracium sarcophylloides Dahlst..

In summary the AI was clearly making up a lot of the names on the list, over half of them. Often it got lucky and these names existed in reality but were wrong for the vernacular name supplied. Very often it got them entirely wrong. It did this even when it was instructed not to “make up” names. It didn’t appear to understand the prompt or the nature of a scientific name. As Hicks, Humphrey & Slater (2024) say “LLMs are simply not designed to accurately represent the way the world is, but rather to give the impression that this is what they’re doing.” Perhaps this is why the answers look like a naive student trying to pass an exam question they don’t really understand.

This was not a serious assessment of the potential of AI to complete the task. Defenders of AI will say that we should have written the prompt differently or that later versions of ChatGPT or a different model will be better. There are enough openly available LLM based systems for anyone to give this a go for themselves. Please try exploring this yourself and report back.

If you would be interested in investigate this further with a more formal study we’d love to collaborate. It may, for example, be possible to use Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) approaches to incorporate a list of plant names into a LLM so that it did not hallucinate names. But even if this was achieved it wouldn’t address the coming storm. Just because we had our own LLM that didn’t invent new names doesn’t mean that all the other LLMs out there aren’t going to carry on inventing names and injecting them into the literature for us to deal with.

There is a potential, perhaps a likelihood, that over the next few years many thousands of apparently new scientific names will be introduced into the literature when people use AI tools to write reports and expand on datasets. These names will then be repeated and perhaps become training material for the next generation of LLMs. Not only will taxonomic specialists have more work to do when monographing a taxon they will also get requests for opinions on fictional taxa. These names could start appearing in ecological impact assessments, on shipping manifests and in product ingredients. There doesn’t seem to be a way to stop this happening and the only real solution is to have an official, global register of scientific names. This is something that has been resisted by the community for many years but looks like an inevitability now.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation programme within the framework of the TETTRIs Project funded under Grant Agreement Nr 101081903.