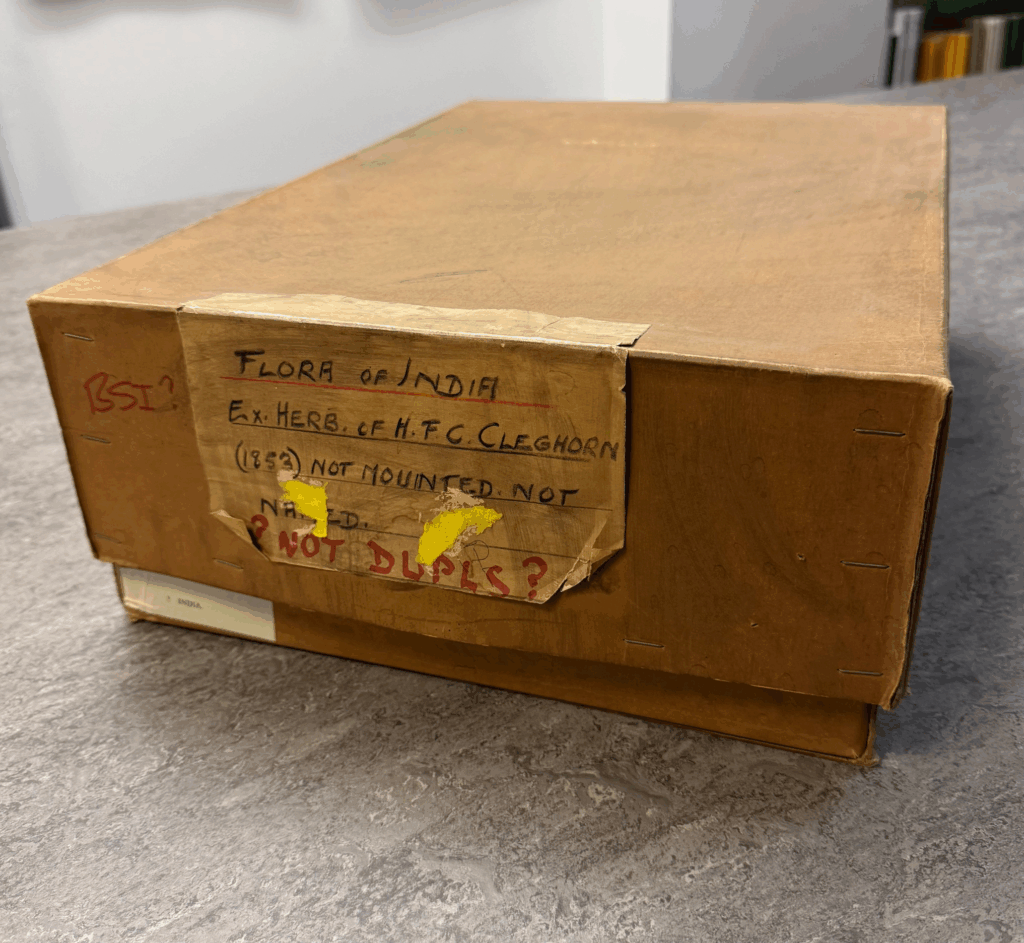

In September 2024 Lesley Scott exhumed a slightly sinister box from the RBGE Long Store. It contained a bundle of unmounted specimens and was labelled: “Flora of India. Ex Herb H.F. C. Cleghorn (1853). Not Mounted. Not Named. ?Not Dupls?“.

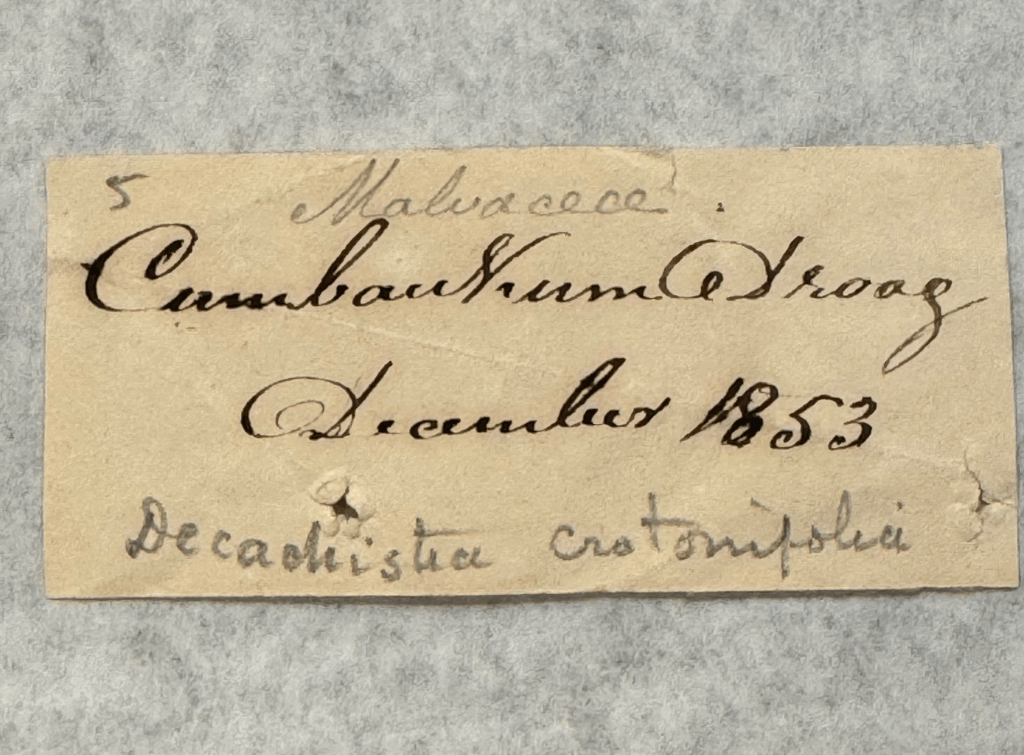

As his biographer the name Cleghorn was enough to arouse my interest. The specimens all have a manuscript label that reads ‘Cumbaukum Droog, Decr/1853’. Interesting as they are, so are the wrappings and accompanying manuscript material: contemporary newspaper ‘flimsies’ from Indian and British newspapers, a journal article, family covers made of Indian ‘country paper’, and two manuscript plant lists.

It appears that Cleghorn never got round to mounting these specimens, which must have come to RBGE in 1896, along with the mounted sheets of his herbarium. Presumably soon after arrival a few of the collection were mounted, as ten with the same label have been found in the RBGE herbarium; the processing must have been interrupted, leaving this fascinating residue entombed for the next century and a quarter.

The first question was who collected them, as the labels are not in Cleghorn’s own hand, though one that is found on many specimens in his herbarium dating from the 1850s. The label on a duplicate of one of the specimens at Kew (see later) does, however, suggest that they were collected by Cleghorn, or a collector on his behalf.

The next point to establish was where the specimens were collected. ‘Cumbaukum Droog’ is clearly an anglicisation and the place that initially came to mind was the temple town of Kumbakonam, but it has no ‘Droog’, i.e., a hill fort. A little digging showed it to refer to Kumbakkam Drug, a flattish-topped peak of 779 metres, in what are now the Nagalpurum (formerly Nagari) Hills in the Eastern Ghats of southern Andhra Pradesh, now spelled Kambakkam Durgam.

What to do with the specimens? As none was in the herbarium a set required to be mounted and kept, but for many there was an abundance of material, from which duplicates could be made to be sent to Kolkata. As the newspaper wrappers offer previously unknown insights into Cleghorn’s reading habits they clearly had to join his collection of prints and drawings in the RBGE archives. The specimens were numbered in the order in which they were found within the box and placed in modern flimsies to await mounting; the newspapers annotated with the number of the related specimen and catalogued.

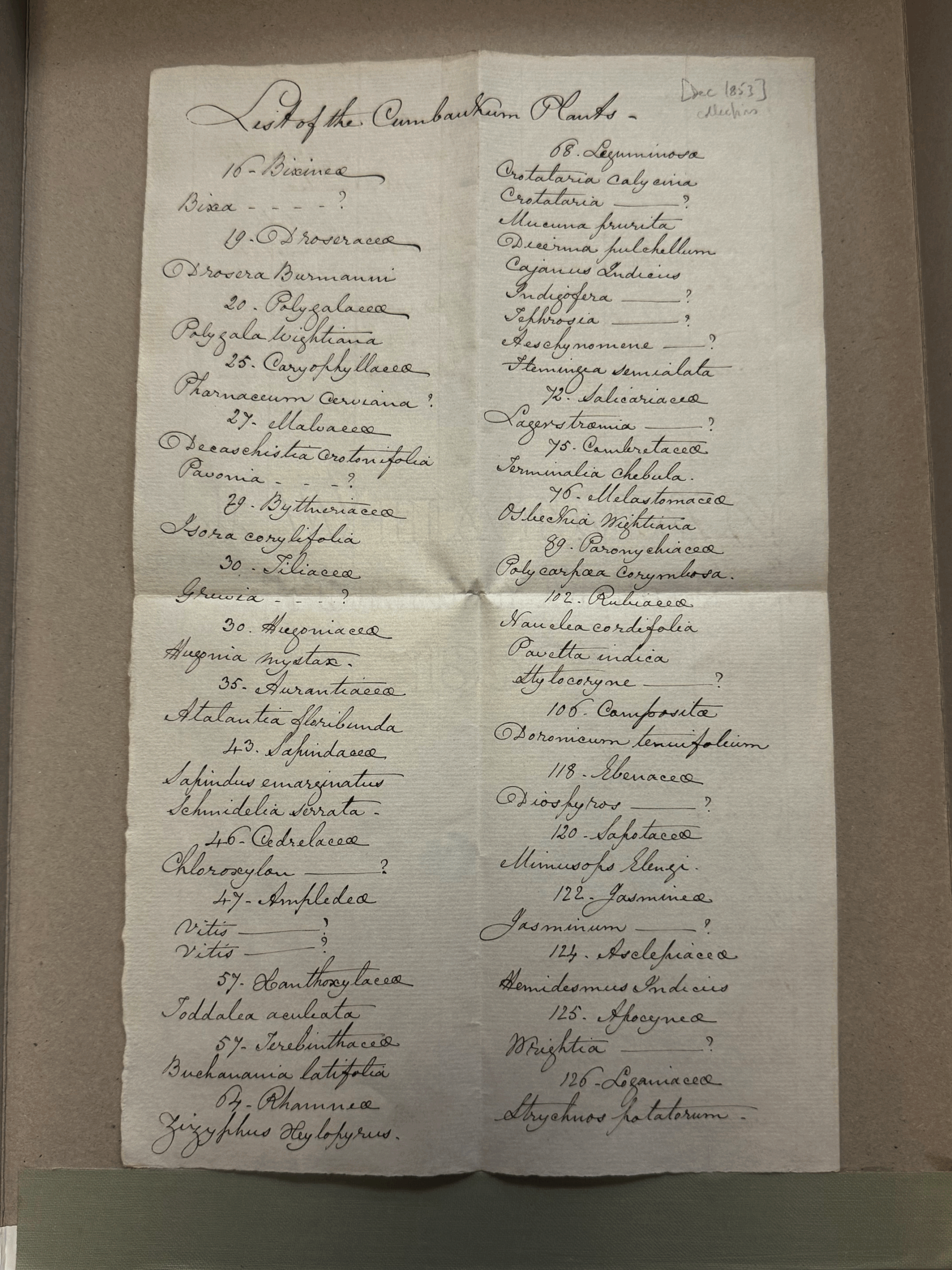

The two manuscript lists

With the specimens is a two-sided ‘List of Cumbaukum Plants’, with 74 names in family order, including the unmounted specimens and those already in the RBGE herbarium – clearly a listing of the collection made in December 1853. As the paper on which it is written is watermarked 1856, it was probably written when Cleghorn or his clerk put them into their newspaper flimsies in 1858/9.

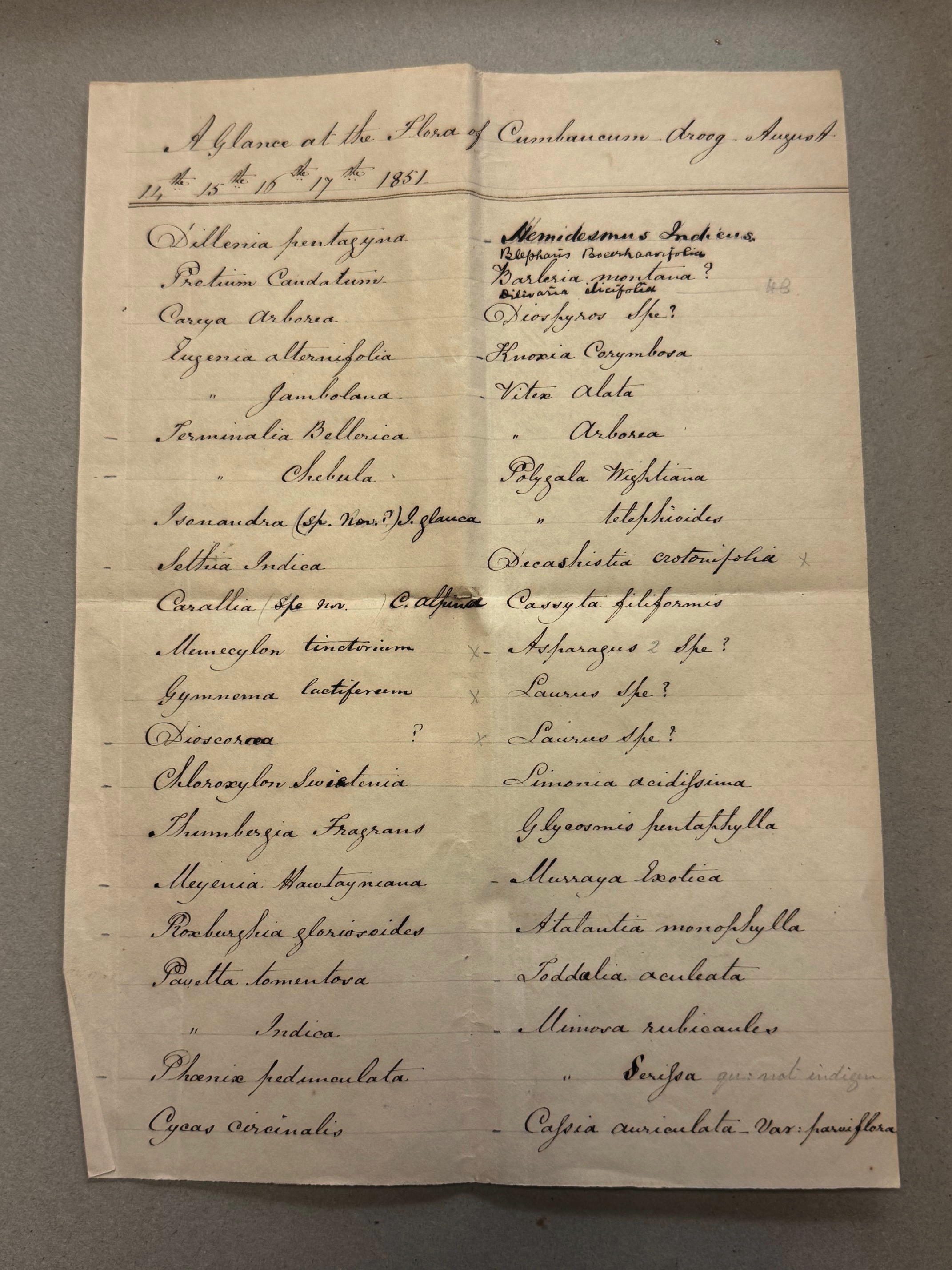

Also with the specimens is a four-page list titled ‘A Glance at the Flora of Cumbaucum droog – August 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th 1851’, in the same hand. This is puzzling as in August 1851 Cleghorn was on leave in Britain, so the list and the visit to which it refers cannot have been made by him. Cleghorn reached Madras in December 1851 and it was only early the following year that he was made Professor of Botany at the Madras Medical College, with access to assistants. Before going on leave to Britain in 1848 he had been in Mysore, where he was not known to have had a botanical establishment other than an un-named ‘Marathi’ artist. But perhaps he had trained an assistant who had left no previous trace and continued botanical work while Cleghorn was in Britain. Was it such a person who went to Cumbaukum Droog in 1851 and realised that it was worth a second look after Cleghorn’s return? From the plant names it was clearly made by someone with considerable botanical knowledge and seems unlikely to have been an East India Company employee or missionary based in the area. Cumbaukum was decidedly off the beaten track, though close to the great pilgrimage town of Tirupathi and the textile one of Sri Kalahasti.

The journal article

Also in the box was a cutting, made by Cleghorn, from the 1835 volume of the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society: an article titled an ‘Account of the Ragery Hills, near Madras’ by a Colonel Monteith. The title is misleading due to a misprint, but Cleghorn corrected the initial ‘R’ to ‘N’ as the article refers to the Nagari (now Nagalpuram) Hills. It was characteristic of Cleghorn to accumulate and annotate such cuttings on topics or plants of interest, but it cannot be known when he first saw the article (written six years before he first reached India), or how he came to realise that the locality might be worthy of botanical investigation.

William Monteith (1790–1864) of the Madras Engineers, after a distinguished career in Persia, became Chief Engineer of Madras from 1832–4 and again from 1836–42. At the time of writing the article he knew personally only one other European who had visited the hills, despite their lying only 50–70 miles from Madras, and ten from Pulicat Lake which was easily reachable by boat. The personal contact was Colonel Cullen, though Monteith believed that two other Europeans had visited the hills – himself being the fourth. William Cullen (1785–1862), also known to Cleghorn, became Resident to the Court of Travancore and had serious botanical interests. Was it this published account, or a personal suggestion from Cullen, that stimulated Cleghorn to visit the hills or to send a collector there?

Colonel Monteith described the topography of the ‘droog’ as: “a fine table-land, of four miles in length by two in breadth; with a stream of water, the ruins of a garden, palace, and some magazines – all, however, overgrown with wood. The height was about eighteen hundred feet, and the climate ten degrees cooler than the plain.”

Monteith published a more detailed article on his expedition in the Madras Journal of Literature and Science in 1836 in which he wrote that the fort was established by ‘Yenga Abasaney, a Poligar chief’ and that it had been taken over by the Nawab of the Carnatic who had built the palace, of which the garden had been cultivated until recently, and who often stayed there.

The wrappers

The specimens were contained in newspaper flimsies dating between 1853 and 1859, most of which were placed in covers made of Indian ‘country’ paper annotated with the numbers and names of 20 plant families. Although the specimens were collected in December 1853, the majority of the newspapers date from 1858/9, presumably when Cleghorn undertook some herbarium curation. They are trimmed to uniform size, c 27 x 44 cm – some more or less whole sheets folded, others cut in half (when the titles are often missing).

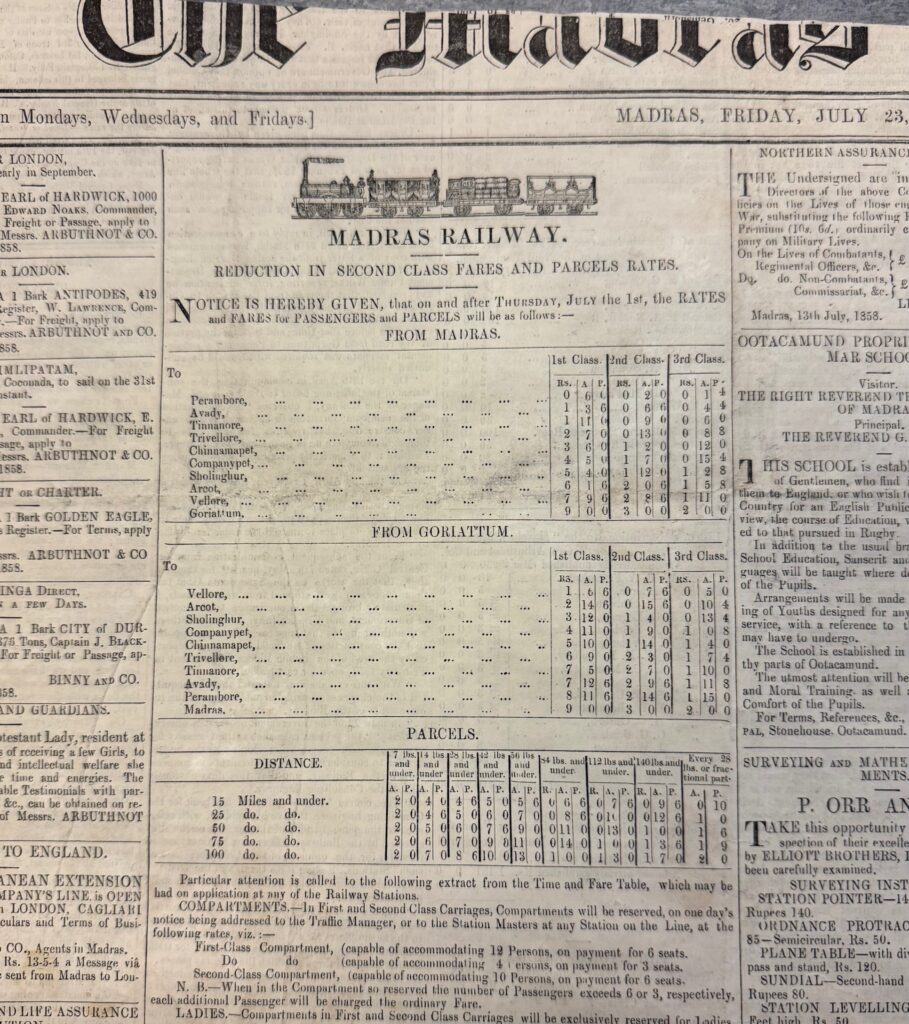

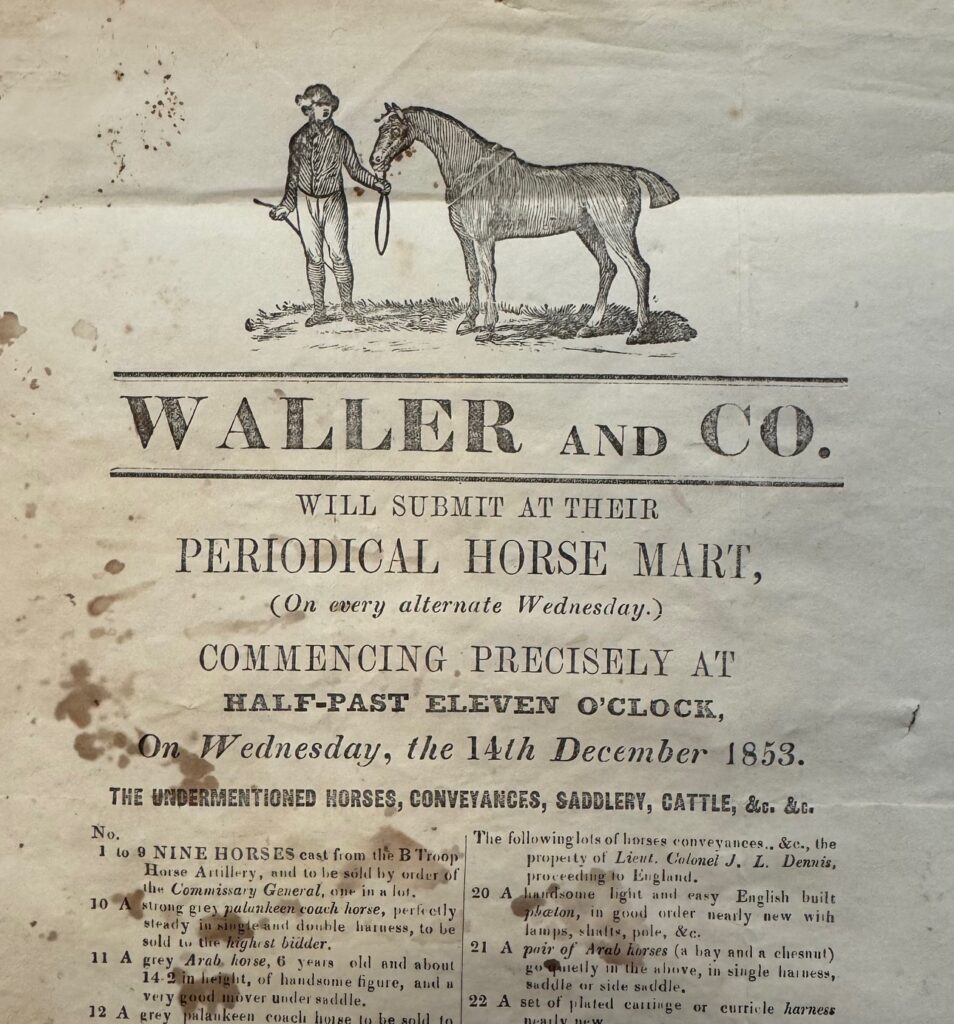

The newspapers are of considerable interest, assuming that they were subscribed to by Cleghorn, rather than bought as scrap paper. Two certainly were his as they are inscribed with his name, title, and address while on tour as Conservator of Forests in Salem and Ooty. These tell us something about his reading habits and suggest a great thirst for news both Indian and from Britain. Also used was also a pamphlet advertising a Madras ‘Periodical Horse Mart’ revealing a previously unknown, though unsurprising, interest in horse flesh; and proof that he subscribed to the Gardeners’ Chronicle, suspected but previously unproven. Of the Indian newspapers was one published in Bangalore (The Bangalore Herald) and seven in Madras (Madras Circulator, The Commercial Gazette, United Service Gazette, The Athenaeum, The Madras Times, The Madras Spectator and the official government Fort St George Gazette). Of those published in Britain the largest number of sheets are from The Overland Mail, with smaller numbers from four others (The Indian News, The Morning Herald, The Record and The Examiner). There is also a single half-sheet from an unidentified Fife newspaper to show that he kept up with news from Scotland.

The articles in the papers dating from 1858/9 are of particular interest, with many articles discussing the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny. Interesting though the ‘news’ items are, the papers are equally intriguing for the advertisements and aspects of social history revealed. It would be easy to get bogged down, so here are only a few items that caught my eye while cataloguing: a meeting of the Madras Photographic Society attended by Sir Walter Elliot (6 April 1858); the opening of the organ by William Hill in St George’s Cathedral (13 September 1858); stained glass fanlights for the cathedral designed by Archibald Cole, Professor Fine Arts in the Madras School of Industrial Art, made by Nathaniel Wood Lavers of London (later Lavers, Barraud & Westlake) (21 January 1859); an advertisement by J. Deschamps offering three pianos by Erard (1 mahogany grand of 7 octaves; 1 mahogany grand square of 6¾ octaves; 1 rosewood cottage of 6¾ octaves) and 1 mahogany grand square by Broadwood (May 1854); J.J. Fonceca & Co offering ‘Likenesses either in Oil, Water Colors, or Crayon … Landscape and Cattle Drawings … charges so regulated with a view to place their services within reach of all (21 January 1859); an auction by Oakes, Partridge and Co. offered a by then very old fashioned ‘square piano by T. Tomkison, in good order’ (6 July 1853).

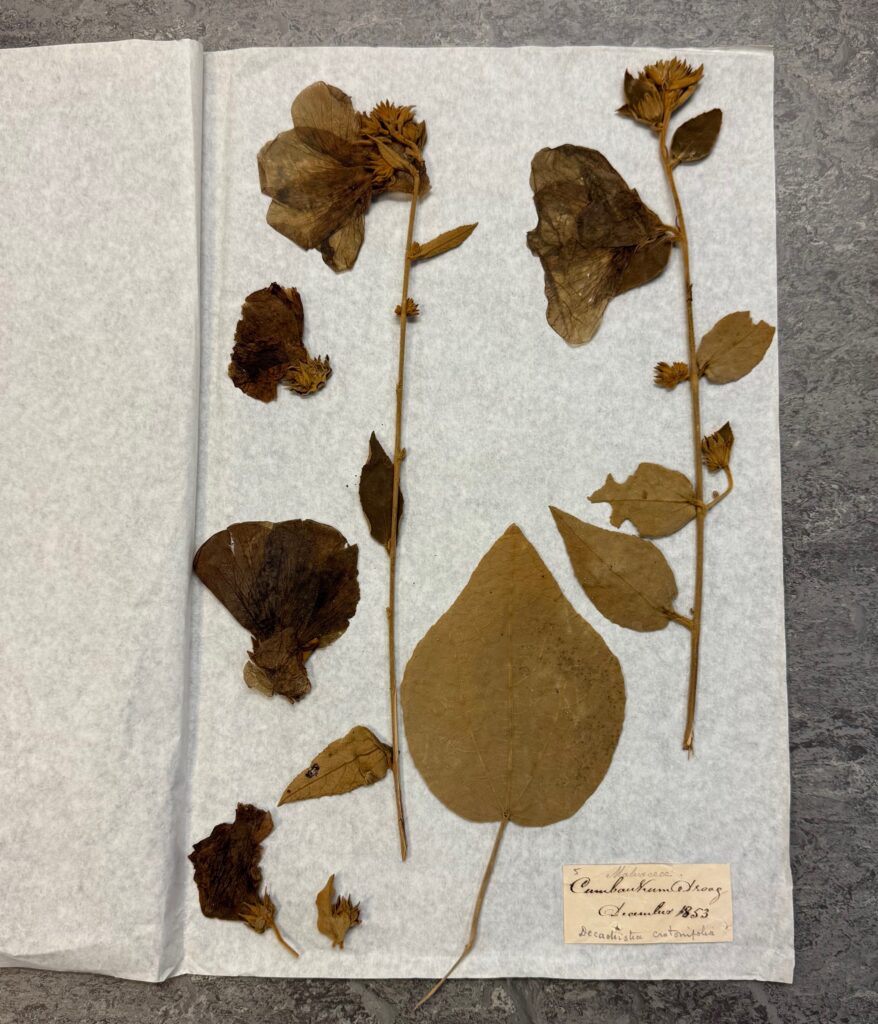

Decaschistia rufa

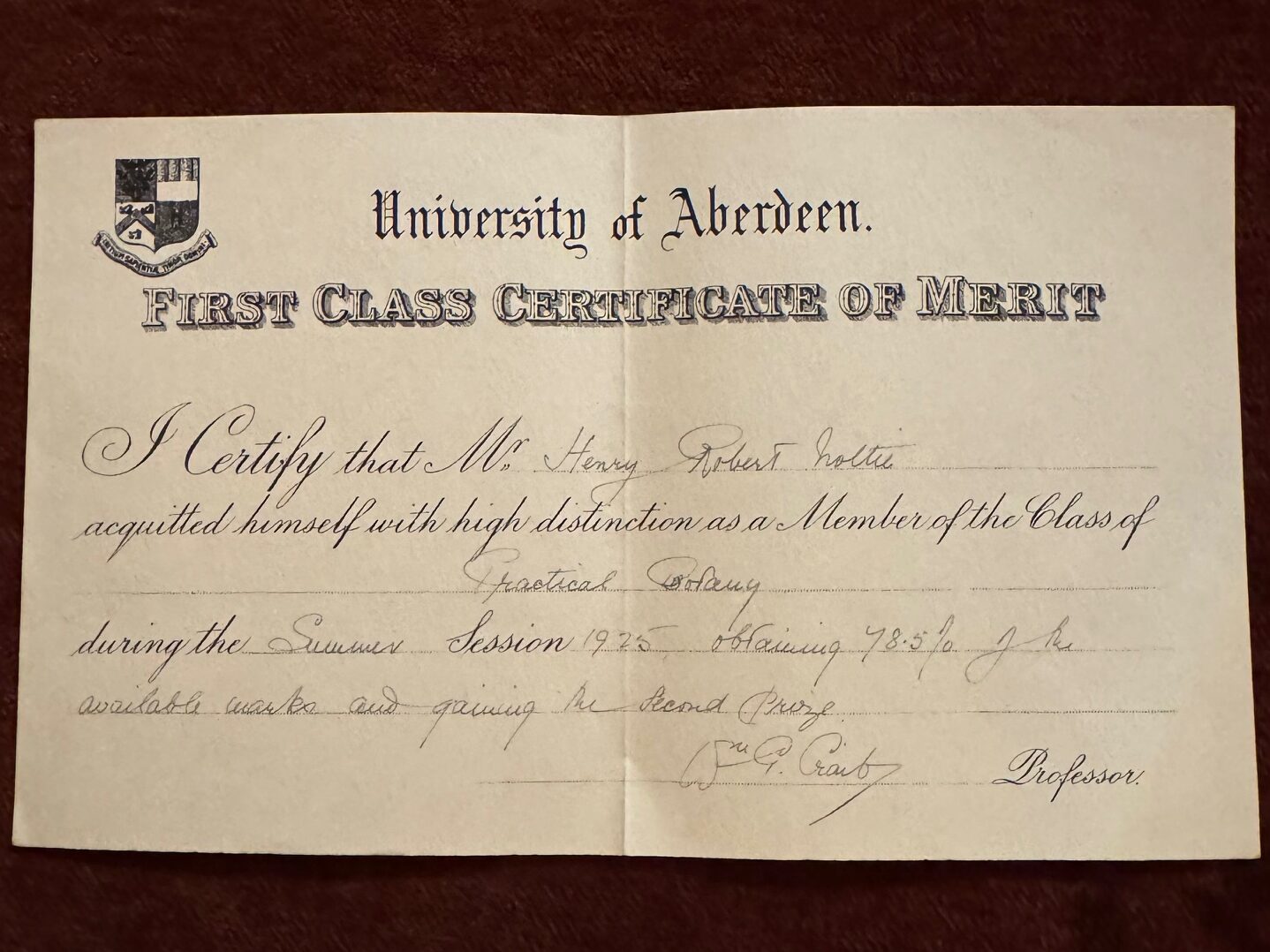

The most interesting specimen in the collection turned out to be a syntype. Identified by Cleghorn as Decaschistia crotonifolia examination of its indumentum and epicalyx segments showed it to be D. rufa, a species described only sixty years after the collection was made – a relative of hibiscus, a large herb, with stems and leaves covered in rusty indumentum. From the dried flowers I guessed that in life they had been dark red but it turns out that, like several other Malvaceae (including okra and some cottons), the flowers in vivo are lemon yellow with a dark purple basal spot, and turn wine red as they age. The species was described in the Kew Bulletin for 1912 by William Grant Craib (1882–1933) while an assistant in the Kew herbarium, but with Indian interests having previously worked as Acting Curator of the Calcutta herbarium. I feel a particular closeness to Craib, as after he became Regius Professor of Botany at Aberdeen in 1920 he taught my father.

The species was based on three specimens in the general herbarium at Kew – two early unlocalised collections: Wallich 1901A (collected by Benjamin Heyne), a J.P. Rottler specimen, and one cited as ‘Kumbākkam Drug, Cleghorn in Herb. Foulkes’. The label of the last in fact reads ‘Cumbaukum Droog, Dec. /53 Dr Cleg.’ and therefore identical to the Edinburgh one. Written on the label is the name ‘Mr Foulkes’ and the locality ‘Nilghiri Hills’, with the latter scored out. The Rev Thomas Foulkes was a missionary, and Cleghorn had close links with missionaries, so must have given him the specimen, who passed it on to Sir William Hooker. It is strange that Cleghorn would give away a specimen that he hadn’t mounted for his own herbarium: did he give Foulkes others from Cumbaukum? The most important point, given that the writing on the labels and associated manuscripts isn’t Cleghorn’s own, is that it almost certainly identifies the Edinburgh collection as having been collected by Cleghorn, or at least a collector under his instruction.

In 1987 the Indian Red Data Book Decaschistia rufa was recorded as: “Endangered. Possible cause of its decline is due to forest clearance, tapping of stem bark by the locals for Cordage purpose. It has not been reported after 1915.“

Some of this appears speculative (has it really declined, or not been adequately sought?), but the date refers to Gamble’s Flora of Madras in which the plant’s distribution is given as ‘Carnatic, Trivallur and Kambakam Hill in Chingleput (Cleghorn), Peninsula (Wall. Cat. 1901 in part)’. This is misleading and suggests that Gamble didn’t know the location of Kambakam Hill, which is nowhere near Chingleput or Trivallur, both localities in the lowlands immediately south and west of Chennai where the plant is unlikely ever to have occurred. Curiously, as not cited, Gamble had collected the plant himself from Ballipalle, a locality in the Eastern Ghats, about 180 km north of Kambakkam.

According to the Red Data Book the Botanical Survey of India failed to find it at the places cited by Gamble in 1983. But in that same year D. cuddapahensis, now treated as synonymous with D. rufa, was described from a specimen from ‘Swamipadalur-Kodur’ collected in 1962. This locality is in the hills between Tirupati and Koduru, only 60 km northwest of Kambakkam. In the 1990s the plant was rediscovered in the ‘Ballepally Reserve Forest, Cuddapah District’, perhaps close to Gamble’s locality. Decaschistia rufa therefore seems to be restricted to the Eastern Ghats of southern Andhra Pradesh between about 13°34’ and 15°14’N, occurring in dry deciduous forest between altitudes of c 150 and 780 metres.