It surprises me that, despite all the advances in AI, computers cannot easily and accurately separate crowns of individual trees in a tropical forest seen from space. It can be done but it is not easy.

Let’s switch from individual crowns to patches of forest, because they’re a little easier for computers to process. When I go onto Google Earth and look at forests in central Africa I can recognise patches of the bemba or Gilbertiodendron dewevrei forest: it’s a darker green and it often runs alongside streams, as well as forming big patches far from water. One site where Gilbertiodedron dewevrei forms mono-dominant stands is in the Sangha Trinational, an area of adjacent National Parks in Cameroon, the Central African Republic and Republic of Congo.

From years of walking through bemba forest, camping in it and collecting herbarium specimens in it, I like to think that sitting at my desk in RBGE I can tell which shade of green is Gilbertiodendron dewevrei in the Sangha Trinational by looking at Google Earth. If the images are high resolution I can zoom in on the individual crowns and see how the consistently tall, narrow crowns look tightly packed from above. They are very clearly different from the adjacent mixed species forest on terra firma with hundreds of different species all with different crown sizes, colours and shapes.

It is pretty easy to separate these two forest types from space and if you have already used Google Earth or Bing Maps from Microsoft I could show you how to identify bemba forest in about twenty seconds or less. But what I can’t do is tell you how good I actually am at recognising it from satellite images. I don’t know how much of it I miss, and how much I mistake other species like parosolier (Musanga cecropioides) that looks the same but only grows along roads in the region. Nor can I tell you how much there is of bemba forest in a given area. I can look at the satellite image and say “there is a lot of it”, and “there is some there”, and “Oh, another bit there”, but I would be very hesitant to give figures for the percentage of forest cover. If there is even a small cloud on the satellite image, I cannot tell what kind of forest is under the cloud.

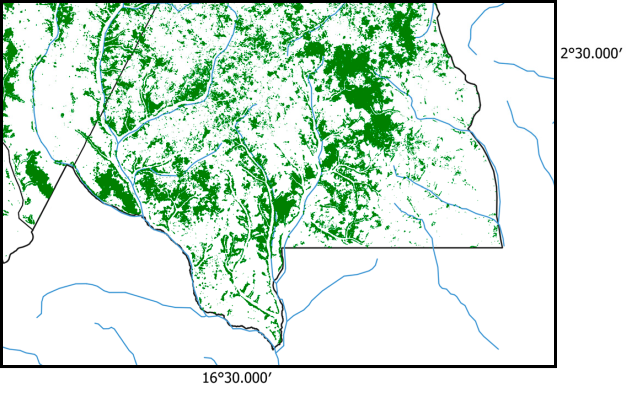

Ellen Heimpel, as part of her PhD research, has published a map of bemba forest across the Sangha Trinational in central Africa (3). From this map covering an area of 7858 km2 anybody can look at any of the 10 x 10 m squares on the map and see whether it is bemba forest. Even if there is cloud cover, or only a low resolution image on Google Earth for a part of the forest, Ellen’s map still gives us the answer. What’s more, she has given a degree of probability of each square allocated to this forest type.

One surprising result from this study is the amount of mono-dominant Gilbertiodendron dewevrei forest. The previous estimate for bemba forest from the Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park in the Republic of Congo was 11% of the area, but Ellen has shown that 30% of the entire Sangha Trinational forest cover is made up of this kind of forest. In the article (3) she reports that there is much more bemba forest in the Nouablé-Ndoki National Park in Republic of Congo than there is in Lobéké National Park in Cameroon.

Why does this matter? It’s important to know how much bemba forest is protected because the plants that grow in bemba forest are not the same as the ones that occur in the other kinds of forest. To preserve the biodiversity of central Africa decision-makers need to know where the different vegetation types are, so that a viable proportion of each one can be included in protected areas. It appears that bemba forest represent very old growth forest in this region and it might take thousands of years for it to grow back. It also seems that bemba forest has greater stores of carbon than the adjacent mixed species forest. All the above make it important that we have good knowledge of where bemba forest occurs.

For research into animal behaviour, knowing where the bemba forest is will help explain how much time gorillas, elephants, chimps and pigs are spending in the bemba forest, and what they are eating there. A recent study reports that gorillas find truffles to eat in bemba forest (1).

Other research topics will require stratified sampling of habitats. An example would be an assessment of fungal diversity of protected areas. Dr Ndolo Ebika at the University of Marien Ngouabi in Brazzaville has already shown that there are many species of edible mushroom only found in the bemba forest (4).

One last example – it can be seen from Ellen’s findings that permanent monitoring forest plots in Gilbertiodendron dewevrei forest are seriously under-represented in the Sangha Trinational compared to the number of plots in mixed species forest.

Best of all, Ellen’s map can be freely downloaded and used by other researchers or conservation managers.

References:

- Abea, G., Ebika, S.T.N., Sanz, C. et al. Long-term observations in the Ndoki forest resolve enduring questions about truffle foraging by western lowland gorillas. Primates 65, 501–514 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-024-01151-7

- Buyck B, Ndolo Ebika ST, De Kesel A, Hofstetter V (2020) Tropical African Cantharellus Adans.: Fr. (Hydnaceae, Cantharellales) with lilac-purplish tinges revisited. Cryptogamie, Mycologie 41: 161–177. https://doi.org/10.5252/cryptogamie-mycologie2020v41a10

- Heimpel, E., Harris, D. J., Mamboueni, J., Morgan, D., Sanz, C., & Ahrends, A. (2025). Mapping of Monodominant Gilbertiodendron dewevrei Forest Across the Western Congo Basin Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sensing, 17(9), 1639. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17091639

- Ndolo Ebika ST, Codjia JEI, Yorou NS, Attibayeba A (2018) Les champignons sauvages comestibles et connaissances endogènes des peuples autochtones Mbènzèlè et Ngombe de la République du Congo. Journal of Applied Biosciences 126: 12675. https://doi.org/10.4314/jab.v126i1.5