On my daily walk to Wardie Bay I pass a curiosity shop of an almost extinct type, whose proprietor Dorian Hiram has the measure of my eclectic tastes. It started with colonial period Indian silver of which he often obtains pieces from the displenishment of houses of the diminishing band of owners with connections to those now denigrated times. The other day I asked him if he had anything of Indian interest, to which the reply was negative. He had, however, recently acquired a collection of small crosses – the sort worn as pendants – one of which he thought might be of interest for its associations. Indeed it was. Constructed from three almost salami-thin slices of a dark brown wood that I took to be oak, it is slightly Celtic in form, with unequal, tapered arms and at their intersection a circle to which is affixed a small, rectangular escutcheon of red gold engraved with what I read as ‘ASTA Navarino 1827’.

The suspension loop is also of red gold. With it came a ticket inscribed in blue biro:

Navarino a bay in the Peloponnese where in 1827 the British Fleet defeated combined Turkish and Egyptian fleets and made possible the liberation of Greece. Wood from the Astia [sic] ship present then.

The great naval battle was fought (the last entirely under sail) in the Bay of Navarino off the south-west coast of the Peloponnese on 20 October 1827. The fleet was not solely British, but a combined one with France and Russia in an alliance formed to try to persuade the Ottoman Empire to allow Greek autonomy. The British fleet was of 12 ships under Admiral Edward Codrington, whose flagship was HMS Asia (the worn lower serif of the inscription turns an ‘I’ into a ‘T’). The Asia was a Royal Naval ship of the second rank with 84 guns; its captain Edward Curzon (1789–1862). The battle was ferocious and led to the defeat of the Turkish-Egyptian fleet with huge loss of life; there were also casualties on the Allied side, with no fewer than 18 killed and 67 wounded on the Asia itself. The ship survived and saw further active service in the eastern Mediterranean until 1858, when it became the guardship for the Portsmouth dockyard; it was not finally decommissioned until 1908. Its figurehead, of a turbaned man was preserved and can still be seen in the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth.

Where, when and by whom the little wooden cross was made cannot be known, but it is likely to have been immediately following the battle. Though finely crafted, it was probably made not by a professional carpenter but by a handy member of the ship’s crew – perhaps as a token for a sweetheart to celebrate its maker’s survival from a British victory. Judging from near contemporary illustrations there must have been plenty of splinters of wood flying around from which it could have been fashioned.

But what came as the most exciting part of its history is that Dorian was not quite correct when he said that he had nothing Indian for me. The Asia turns out to have been built for the Royal Navy, between 1822 and 1824, by Nowrojee Jamsetjee Wadia (1774–1860), the fourth of the great Parsi master-shipbuilders of the Bombay dockyard, whose descendant I stayed with in Pune in 2000, while researching The Dapuri Drawings, and on several subsequent occasions. A portrait of Wadia by J. Dorman at the National Maritime Museum (on loan from the Royal Asiatic Society) shows him seated, with a drawing of the Asia as a significant prop on an adjacent table.

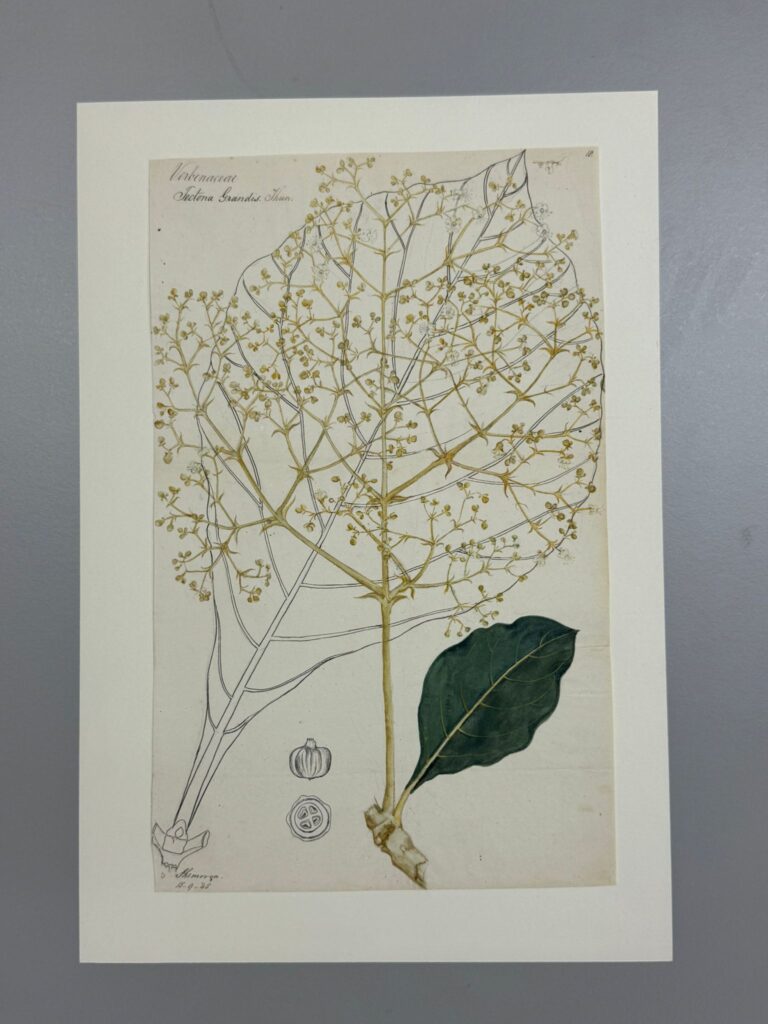

The wood is therefore not British oak as I’d thought but ‘Indian oak’, the name by which teak (Tectona grandis) was sometimes known – for the properties of its timber rather than for anything about its physical appearance as it has large oblong-ovate leaves and small, cream flowers in large, frothy panicles. Traditionally placed in the family Verbenaceae it has now been transferred to Labiatae (Lamiaceae if you must).

At this date the main sources of teak for the Bombay dockyard were still the forests of western India, though these were rapidly becoming depleted. These included Malabar in the south, the Dang Forests of Gujarat in the north, and between thm the ‘teak villages of the Tulleh Peta including Doongrowlee’ on the Western Ghats to the west of Poona in Maharashtra. All of these were among the forests visited by Alexander Gibson with the start of government-controlled conservancy of teak in the Bombay Presidency in 1840, for use in the dockyards. In 1847 Gibson was made the first Conservator of Forests for Bombay, though the word ‘conservator’ should not be confused with modern ‘conservation’: as Deborah Sutton pointed out mid-nineteenth century conservation was ‘the management of an ordered taxation of resource usage’. It was the botanical drawings, commissioned in part as a by-product of Gibson’s forestry activities, that was my point of introduction to the study of Indian environmental history, which continued with my work on Hugh Cleghorn. In 1856 Cleghorn became the first Conservator of Forests for the Madras Presidency and assumed management of some of the Malabar teak forests from Bombay.

With the ship Asia there turns out to be a second Indian connection as its captain, Edward Curzon, was an illegitimate son of Nathaniel Curzon, second Baron Scarsdale, great grandfather of that ‘most superior person’ George Nathaniel Curzon, Viceroy and first Marquess Curzon of Kedleston.

With thanks for Alison Ohta of the Royal Asiatic Society for supplying the portrait of Wadia.