A checklist of the plant family Putranjivaceae has just been published in the Edinburgh Journal of Botany (Quintanar et al. 2025). It’s a list of all the species accepted in the family. But it is more than a list of names to be checked off. Every scientific name that has ever been associated with the family has been researched. There are 223 species accepted in the family, but an additional 248 species names associated with this family are also treated. Most of the 471 species names are listed as synonyms in the checklist.

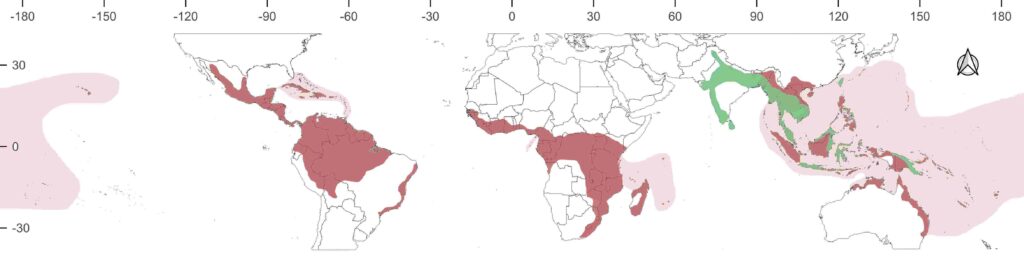

The family Putranjivaceae occurs in most tropical countries and in some more temperate areas from Florida to Japan. Different taxonomists are working on different species in different countries. New species are being described all the time. After the checklist was sent out for peer review, new names were published by colleagues in Cuba and Peru. Those new names were added to the manuscript.

The distribution of Putranjivaceae across many countries is the main reason why it is so important to assemble and check all the names that have been published in a plant group. This allows researchers to avoid the simple error of using a name that has been already used for a new species. Having all the names for this family checked and assembled in one place by taxonomists means that any researcher can quickly see what names have already been used and how.

Another important benefit of this checklist is that it gives an up-to-date snapshot of the present-day view on which species names are accepted by taxonomists. Naming and classifying some groups of plants can be more dynamic than the average layperson might expect. Even for taxonomists, keeping up with changing names and differing taxonomic concepts is not a trivial pursuit.

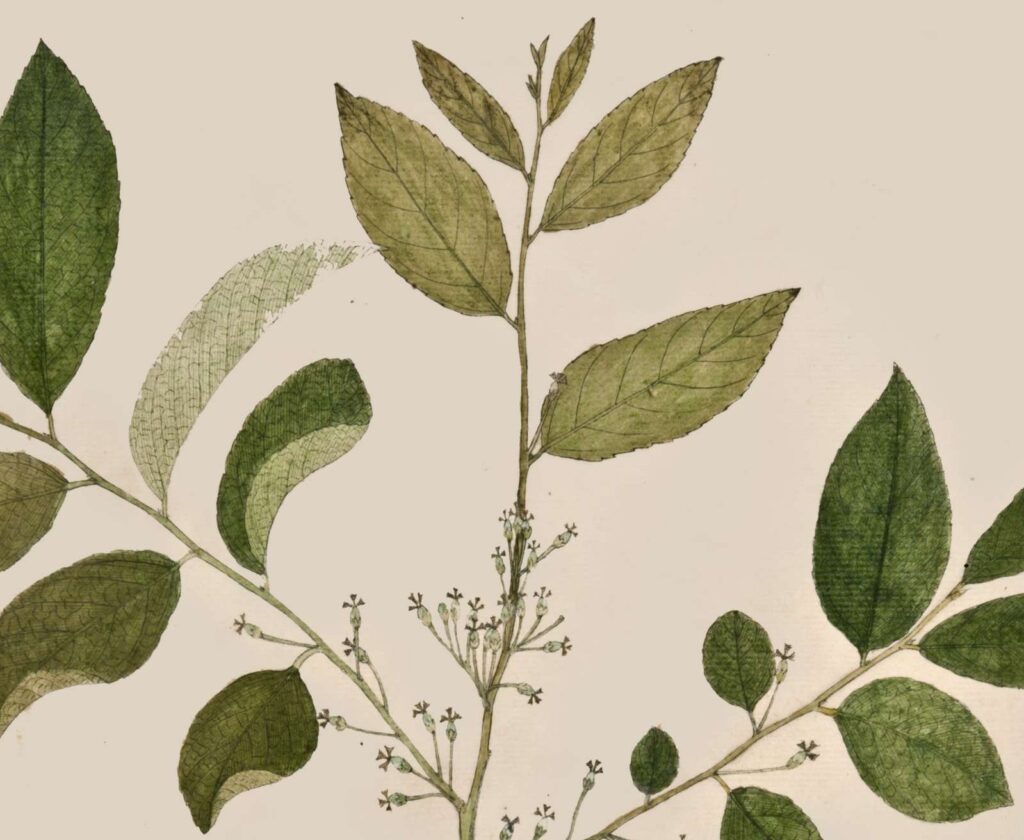

Every scientific species name for plants and fungi should have a type specimen and all the types were listed for the names in the checklist. Some new types had to be chosen, and this was done following the strict set of rules in the international code of nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants (Turland et al. 2025). Most types are specimens for flowering plants, but exceptionally illustrations can be used as types. As part of the research that went into the checklist the herbarium at Taiwan Forestry Research Institute provided information on type specimens collected by Japanese botanists in the 1920s and the Botanical Survey of India gave permission for a type illustration of Putranjiva roxburghii to be reproduced in the checklist. Several herbaria were visited, and many more online herbarium resources were used to check type specimens and match them to their designation as types in the literature.

Students starting to study taxonomy sometimes think that the place to look for the type status is on the specimen or on online specimen databases. Any experienced taxonomist will tell you that the place to find the type of a name is in the literature where the name was published, which is called the protologue. The original publication of all the name were read and each name researched carefully. The protologues were in many different languages from Chinese and Japanese to Dutch and Latin and we used several online translation websites as well as checking with native speakers (except Latin!). Some names were found not even to belong in the family. Other scientific names were not validly published and had to be rejected.

If we take one name from the checklist as an example, we can look at the history of a scientific plant name and look at the plant. The name Drypetes polyantha was first published by Ferdinand Pax and Käthe Hoffmann in 1922, using specimens first collected by Johannes Mildbraed in 1914 in Cameroon. The name then sunk with hardly a trace as far as we can see for more than fifty years. It was picked up by Index Kewensis but it was not used in any taxonomic works. The type specimens held in Berlin were destroyed in 1943 by bombing during the second world war. For botanists working in Cameroon (and neighbouring Central African Republic and Republic of Congo) the name Drypetes polyantha was hardly used, as nobody knew to which plant it should be applied. The original description was in Latin and none of the type specimens could be found. In 1995 I was working on identifying herbarium specimens collected in the Central African Republic in what is now the Sangha Trinational World Heritage Site I found the description of Drypetes polyantha and I used the name for several specimens I had collected (Harris 2002). Later in 2023 working on the checklist we found a duplicate of a specimen collected by Mildbraed in Cameroon that had been distributed to Kew before the Second World War that we consider to be the only remaining type material. Fortunately, it matches the more recently collected material of what I called Drypetes polyantha in 1995.

Now Drypetes polyantha is better known. It described in a photoguide to the trees of Congo (Harris et al 2008). It has also been assessed for the International Union of Conservation Red List of Threatened Species, and it is widespread and common enough not be considered as threated.

By going through all the published names in Putranjivaceae systematically and listing the countries where the species are said to occur, we have facilitated the work of others working in different parts so the world.

Nomenclatural checklists are a standard procedure in taxonomy and previous checklists produced by RBGE staff were used as models at the start of the Putranjivaceae checklist. For example, a checklist to the species of the mega-diverse and beautiful genus Cyrtandra in Borneo by Hannah Atkins and colleagues was also published in the Edinburgh Journal of Botany (Atkins et al 2024) and the checklist of (another mega-diverse and beautiful genus) Begonia in South East Asia by Mark Hughes which has according to Google Scholar has been cited 154 times, showing the impact of this kind of checklist (Hughes 2004).

What this checklist of Putranjivaceae has done differently to other checklists is that we have added in permanent identifiers as internet links to the two major botanical databases. These links take you with one mouse-click from the checklist, straight to the appropriate page on the online databases. The first of these databases is the International Plant Names Index, (https://www.ipni.org/) a resource that can trace its origin back to Charles Darwin. He was so frustrated by a lack of a one-stop resource for plant names that he left money in his will in 1852 for the establishment of and list of plant names. That money was used to establish Index Kewensis which was first published in 1893 providing a long running resource which joined two other similar lists in 1999 to form the International Plant Names Index.

The newer and even more ambitious online database World Flora Online brings together many institutions from around the world with the aim to provide “an online flora of all known plants” and thus achieve Target 1 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation. RBGE is a founder member of the World Flora Online consortium that now has 58 institutions from around the world as members with more joining each month. With a distributed network of taxonomic specialist and a range of institutional support the World Flora Online is the global botanical database to watch.

The authors of the Putranjivaceae checklist are members of the World Flora Online TEN (Taxonomic Expert Network) for the family. The checklist ends its discussion section with an invitation for other taxonomists to join the TEN for Putranjivaceae.

By hardwiring permanent links for names and taxon concepts into the two major databases for plant names we are making the information we provide as useful as possible to the user and also optimising the long-term functionality of the checklist. Because the authors of the Putranjivaceae are members of the TEN for Putranjivaceae we see this checklist as a building block, and we will continue to feed our future findings into the World Flora Online.

One way to think of a nomenclature checklist is like the scaffolding on which future research progress will be made. By assembling all the literature and information we allow anybody else starting to work on Putranjivaceae to start with all the information presented in this checklist. In a time of faster and faster progress nobody wants to spend time revisiting the decisions of the past unless they can be shown to be wrong. Here we have all the information assembled, the previous taxonomic decisions assessed, new decisions made and supported with evidence, and all summarised in one publication.

“Hard-wiring”, “building block”, “scaffolding”: these are expressions from the construction industry – it’s tempting to slip in another and describe this checklist as a “solid foundation” for future research on this poorly known group of plants.

References

Atkins, H., Bramley, G., Kartonegoro, A., & Sang, J. (2024). Preliminary checklist of Bornean Cyrtandra (Gesneriaceae). Edinburgh Journal of Botany, 81, 1-46.

Barberá, P., Quintanar, A., Harris, D.J. & Stévart, T. 2021. Drypetes polyantha. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021:

Harris D.J. (2002). The Vascular Plants of the Dzanga-Sangha Reserve, Central African Republic. Meise, National Botanic Garden (Belgium) 1-274.

Harris D.J. , Moutsamboté J.-M., Kami E., Florence J., Bridgewater S. & Wortley A.H. (2011) An introduction to the Trees from the North of the Republic of Congo. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. 1-208.

Hughes, M. (2008). An annotated checklist of southeast Asian Begonia. Edinburgh: Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

Quintanar, A., Barberá, P., Elliot, A. & Harris, D.J. (2025) The Putranjivaceae of the world: a cross-referenced checklist of the genera and the species. Edinburgh Journal of Botany 82: 1-146. https://doi.org/10.24823/ejb.2025.2058

Turland N.J., et al. (eds) (2025). International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Madrid Code). Regnum Vegetabile 162. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226839479.001.0001