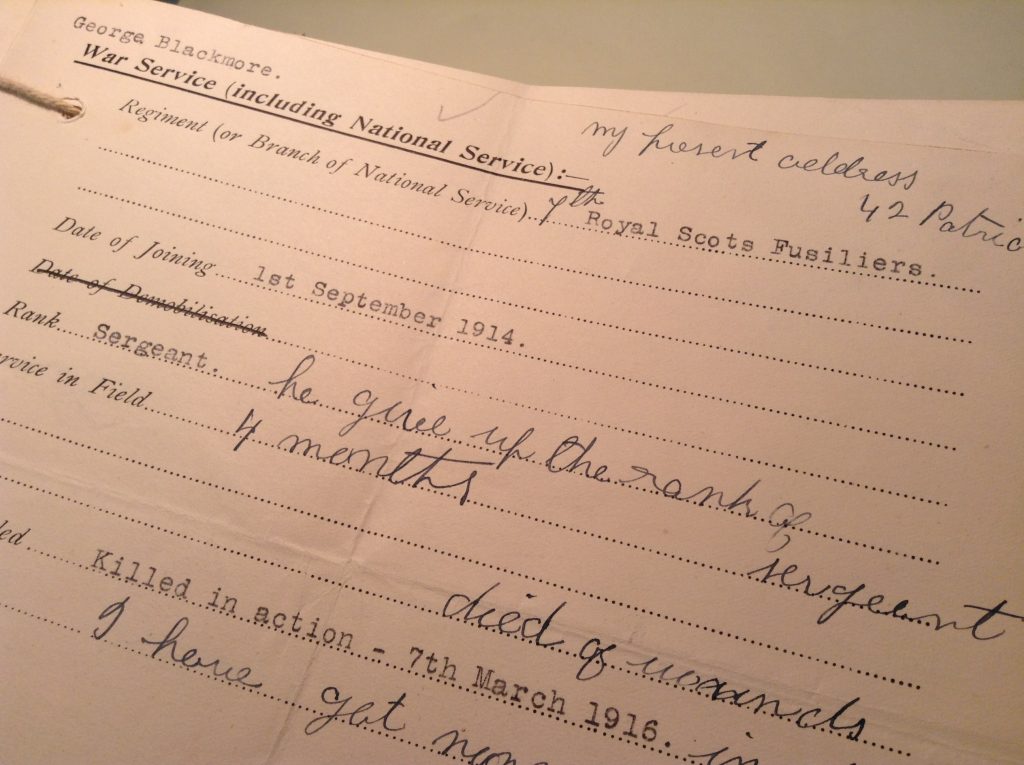

In March 2016 we remembered the life of George Blackmore, a man who worked at RBGE as a labourer until the beginning of the First World War in 1914. Documents held at RBGE give the briefest of information about him; his employment as labourer at RBGE began on the 2nd October 1913 and he enlisted with the 7th Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the 1st September 1914. His rank is given as Sergeant, but a note from his wife Margaret on our service record card tells us that he gave up this rank, with no reason given, making him a Private. He died of wounds received in action on the 7th March 1916.

Papaver rhoeas from M.A. Burnett’s ‘Plantae utiliores; or Illustrations of Useful Plants, employed in the Arts and Medicine’, 1842

Genealogical research can tell us more about Blackmore’s life, and I’m very grateful to Garry Ketchen for conducting this research and allowing me to use it. Blackmore was probably born in 1870 in Edinburgh to Henry, a groom, and Susanna, a laundress. George Blackmore became a mason before enlisting with the 2nd then 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers in Ayr in October 1892. He served in East India and eventually attained the rank of Lance Corporal before being discharged in October 1913, at which point his employment at RBGE started. At the outbreak of War, Blackmore would have been around 44 years of age, older than most of his colleagues who were enlisting, but the army would have been keen to recruit experienced soldiers and Blackmore re-enlists in Edinburgh on the 1st September 1914, becoming Private 7494 of the 7th Royal Scots Fusiliers. An extensive period of training followed in England (Aldershot, Bramshott, Basingstoke and Draycott) before Blackmore’s battalion finally entered the theatre of war in July 1915, although Ketchen’s research states that Blackmore did not reach France until the 17th November 1915. Less than four months later, on the 7th March 1916, he was dead, his remains now buried in the Lapugnoy Cemetery near Bethune.

There was no specific battle that day. It appears that the Royal Scots Fusiliers were engaged in holding the Western Front line near Loos where so many Scottish soldiers had lost their lives since the British army began their offensive against the German opposition there in September the year before. John Buchan describes the winter the 7th Battalion would have just experienced in his book outlining the ‘History of the Royal Scots Fusiliers (1678-1918)’ published in 1925:

“In this area [Loos] throughout the winter of 1915-16 the trials of the Fifteenth Division were very severe. The Hohenzollern sector, in particular, could perhaps be best described as an open battlefield when taken over in October 1915 by the 45th Brigade, of which the 7th Royal Scots Fusiliers formed part… Communications through the old British trench system, across the previous no-man’s land, to the old German trenches now held by our own men, were lengthy as well as exposed, so that reliefs and the tasks of carrying-parties were both perilous and exhausting. The mine warfare, combined with the heavy hostile artillery and trench mortar fire, took its toll. The strain on battalions can perhaps best be understood when it is realised that during two of these months in the trenches, the Fifteenth Division suffered 3,000 casualties.”

It’s obvious there would still have been skirmishes and sniper attacks on the front-line on a daily basis and it appears that George Blackmore may have been a victim of one of these.

In Buchan’s book I found the below poem, written by Lieut-Col A.M.H. Forbes, a fellow Royal Scots Fusilier, in which he describes with humour some of the conditions experienced by the soldiers during their first winter in France in 1914. I think Blackmore may have had similar experiences the following winter and so I include it here.

“I came to France prepared to shed my blood,

But not to perish miserably in mud,

I’m ready to attack with might and main,

And here I’ve sat six weeks inside a drain,

While all that’s left of Bill, who took a snooze,

Is just a bayonet rising from the ooze.-

You find me out a bit of ground that’s dry

And I’ll soon show the savage Alleman why;

But now I can’t advance against the brutes

With half a ton of France upon my boots!”