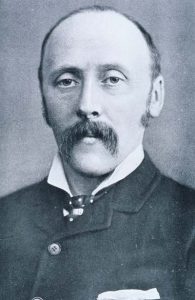

Born on the 31st March 1853, the son of John Hutton Balfour who was Regius Keeper at RBGE between 1845 and 1879, Isaac Bayley Balfour grew up up in very close contact with the Botanic Garden. Educated at Edinburgh University, he became its first Doctor of Science (with First Class Honours), for a thesis inspired by his role as expedition botanist on the Challenger voyage to Rodriguez. A further expedition, undertaken whilst he was Professor of Botany at Glasgow, explored the botany and geology of the island of Socotra. Qualifications are all very well though – when Balfour became Regius Keeper at RBGE in 1888, how did he do?

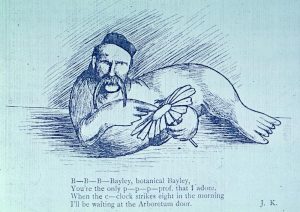

Isaac Bayley Balfour benefitted the Garden greatly as a visionary administrator, dedicated to reorganising and equipping the Garden for the 20th century. He opposed a proposal to transfer the RBGE to the University, successfully arguing instead that it become wholly a Crown body; thus from 1889 the RBGE came into the care of the Commissioners of Works and Public Buildings. His period of office saw the entire main range of glasshouses rebuilt and a new Botany Building with laboratories and offices constructed at 20 Inverleith Row. In the Garden itself, he oversaw the rearrangement of the tree collection, the creation of the Herbaceous Border and the reconstruction of the Rock Garden. He used a system of apprentice gardeners and foresters to provide the extra manpower, providing them with evening classes and examinations to enhance their future job prospects. He was a hard task master, but his workers were keen to impress him. One story tells of his men going flat out to shift a large mound of earth in one day during the Rock Garden rennovations in around 1910, as Balfour had thought it would look better elsewhere, only for him to tell them to move it back the next day!

Bayley Balfour transformed the Garden’s work, appointing a wealth of new staff for taxonomic research. This was very much linked to the explosion of interest in Sino-Himalayan Floras, rhododendrons and primulas in particular, which Balfour helped to boost in 1904 by recommending herbarium clerk George Forrest for a Chinese plant collecting expedition. Forrest went on to complete seven successful expeditions to Yunnan in SW China, becoming the most prolific plant collector in that area. Like his father, Bayley Balfour also excelled at teaching, which he also invigorated by launching the horticultural apprenticeships which later led to the globally revered Diploma of Horticulture Edinburgh.

Balfour received a Knighthood in 1920 not for his incredible career in botany and education, but for his services in connection to the Great War.

“no-one in my Garden including myself was indispensable. I have been taken at my word and excepting Mr. Harrow and a youngster who was discharged from the Army after some months’ service I have not a man looking after my plants who would have been allowed to come near them in the old days…” I.B. Balfour to Reginald Farrer, 9 Feb 1917 (RJF/1/1/2/53)

“Fortunately, the loyalty and fine spirit of all who are left carried us over our most critical period, but now I have to carry on as best as I can with such old men of non-military age or younger men unfit as we can secure from the ranks of the unemployed. It makes gardening very difficult and I fear – nay I know – that our collections are suffering sadly. However nothing matters here but the war. A temporary set-back to our gardening efforts is nothing to the saving of our race from suppression – for that is the inwardness of the whole business.” I.B. Balfour to R. Farrer, 6 Feb 1915 (RJF/1/1/1/16)

He certainly would not have been the only employer to lose a high percentage of his workforce to the army in the opening weeks of the conflict declared in August 1914 (56 out of a total staff number of 110 within the first few weeks, rising to 73 by 1918, with 20 losing their lives), but he did more than that. Being knowledgeable in military medicine, he did much to promote the collection and use of sphagnum or bog moss (Sphagnum papillosum and S. palustre) so that it could be used to dress wounds in military hospitals, undoubtedly saving many lives and limbs. Once sterilised and dried, sphagnum has numerous qualities preferable to those of cotton wool making it ideal for use as a dressing – it can hold around 20 times its own weight in fluid making it more apsorptive than cotton wool, and it also posseses antiseptic qualities, feels cool when applied and was easily obtainable in Britain meaning it didn’t have to be imported. It wasn’t long before those living nearby boggy areas (Balfour’s deputy produced a list in 1916 of where these areas could be found in Scotland, as well as being involved in the Timber Supply Department) were able to contribute to the war effort by collecting and drying sphagnum. He was also amongst those to suffer great personal loss, losing his only son, also named Isaac Bayley, or ‘Bay’, at Gallipoli in June 1915.

Balfour retired in March 1922 as his health was failing him. He moved to Haslemere in Surrey, perhaps in an attempt to improve his constitution, but died on the 30th November 1922.

With thanks to Alan Bennell and Peter Ayres for providing me with information I used in this article.

2 Comments

2 Pingbacks