Private John Mathieson Brown’s grave in the Jerusalem War Cemetery, courtesy of the War Graves Photographic Project.

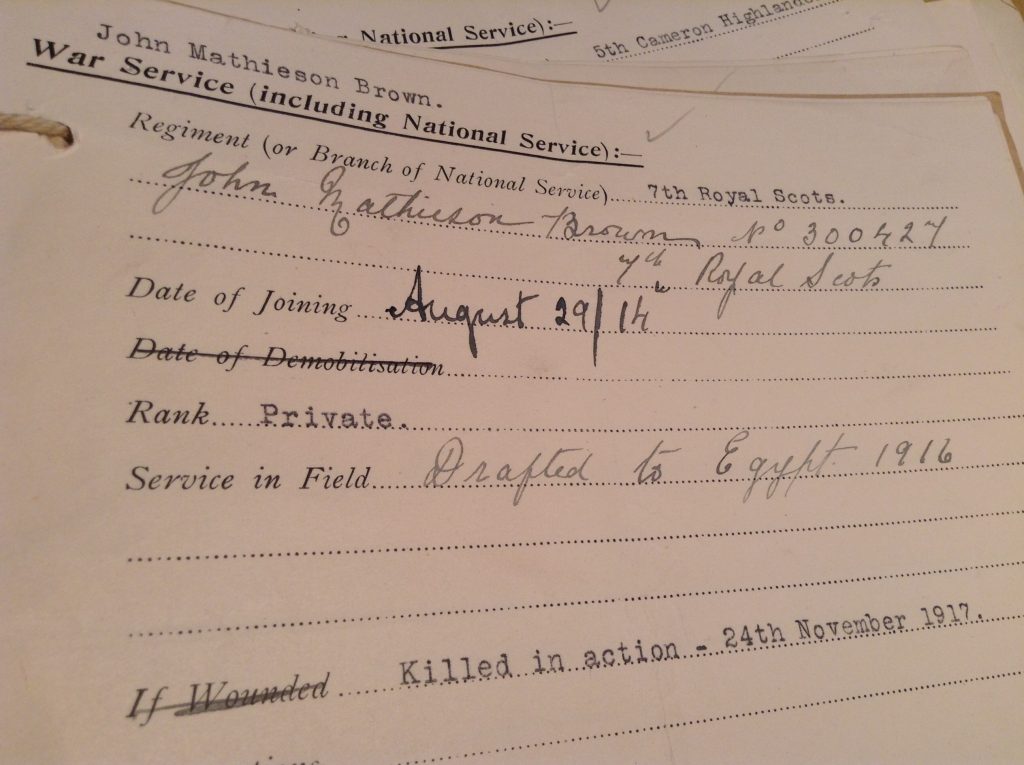

The story of Private John Mathieson Brown, who was killed on the 24th November 1917, takes us away from the Western Front in Belgium and France, and focusses our attention on what was happening in Egypt and Palestine.

Brown was born around August 1887 in Forres, near Elgin, the son of Rebecca Mathieson who was a Domestic Cook. He wasn’t employed at RBGE for long, joining us as a Labourer on the 8th August 1914, 4 days after war was declared. Three weeks later he left to enlist with the 7th Battalion of the Royal Scots. He perhaps wasn’t the perfect soldier during his training, picking up small punishments for minor offences like being late for roll call, being disrespectful to his commanding officers and losing an item of government property, but he completed his training, during which time he married his fiancée Marjory White in Leith a couple of days before Christmas 1915. It seems that after this he was only granted 4 days of leave in October 1916, during which time I imagine he travelled back to Edinburgh to say goodbye to Marjory, before leaving the U.K. in December 1916 to travel with his Battalion to Alexandria where he began his service with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. He never had to face the trenches, mud and barbed wire of the Western Front, but had to deal instead with the sand, drought and cactus hedges of Egypt and Palestine.

Troops were being sent to Egypt to defend the Suez Canal which had been attacked by Turkish troops at the beginning of 1916. General Murray, the Commander in charge there was working on the idea that the best way to defend the Suez Canal was to gain control of the Sinai Peninsula further east, but he became ambitious and this changed to a campaign to take Gaza, and eventually, by the end of 1917, Jerusalem.

Private Brown was wounded a couple of times in 1917, in April badly enough to require a spell in hospital – a gunshot wound to his leg attained during the unsuccessful Second Battle of Gaza on the 19th April. The 7th Royal Scots were attempting to capture one of the hills to the south of Gaza, but were flanked by Turkish soldiers on higher ground on both sides making it an impossible objective to achieve at that time. General Murray was replaced by General Allenby in June who instead opted to attack Beersheba to the southeast of Gaza, which eventually fell at the end of October before circling round and attempting Gaza again which the British troops were able to occupy on the 7th November. The next objective was Jerusalem.

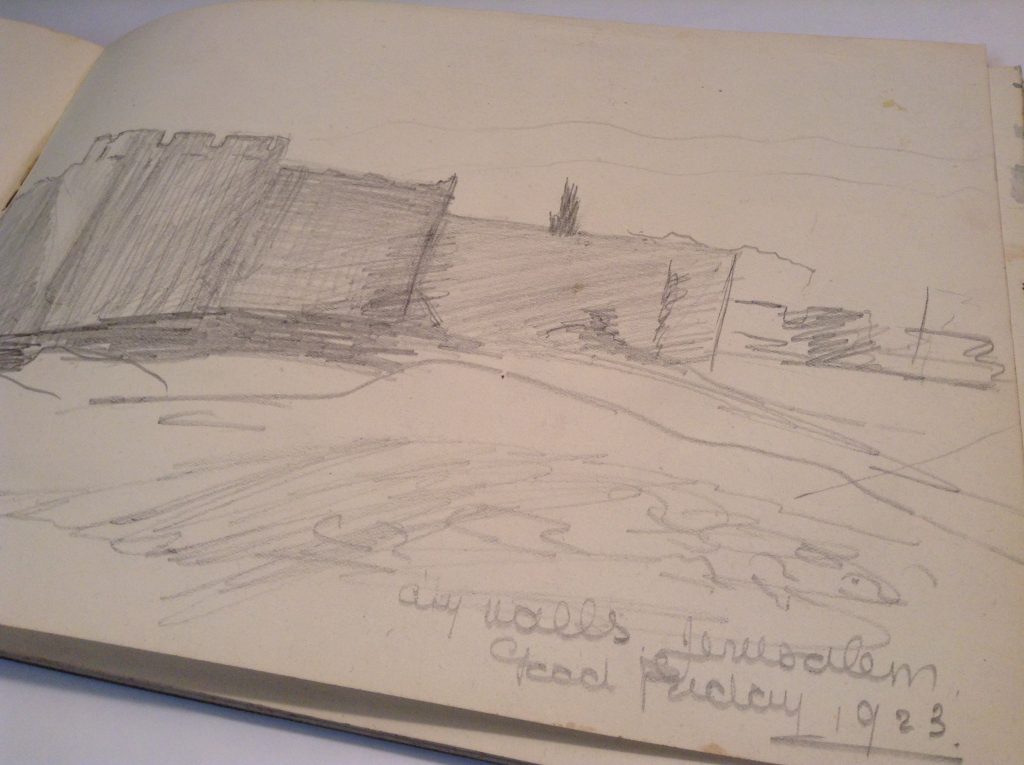

City Walls, Jerusalem, Good Friday, 1923 – a pencil sketch by Isobel Wylie Hutchison from her collection in the RBGE Archives

Jerusalem’s Holy status meant that Allenby had no wish to bring the fight to the city itself – he needed support at home for his campaign – so his strategy depended on taking villages on the outskirts of Jerusalem, thus cutting off the Turks’ means of retreat – as their options reduced, it was hoped they would eventually flee the city. Allenby aimed to cut off the road north out of Jerusalem and so it was that Private Brown and his 7th Royal Scots found themselves to the northwest of Jerusalem mid-November, attempting to seize the strategically important hill of Nebi Samwil. Major John Ewing’s history of the Royal Scots, published in 1925, outlines what happened to the 7th Battalion in what became known as the Battle of Nebi Samwil on the 24th November 1917. Their task that day was to clear the walled enclosures and orchards that surrounded the mosque on the hill’s summit, and then to sweep any remaining Turkish troops from the remainder of the ridge – it turned out to be an impossible task without artillery support (support they didn’t have). Number 1 Company advanced around 100 yards at noon, passing on the right hand side of the mosque and could not proceed any further due to Turkish fire that hit them from the front and the sides. Number 4 Company went around the left hand side of the mosque, reaching a courtyard that had a shed in it. When the courtyard became the target of the Turks’ bombs and bullets the Scots sheltered in the shed, some taking to the roof to fire back down on the Turks, but this had been anticipated and the Turks turned their fire on the shed roof, killing many. The remaining soldiers saw that a frontal assault would not work and decided to take to the slopes, but their way out of the courtyard was now covered by Turkish fire and many were killed in the attempt. Setting up a Lewis gun failed when the Turks aimed their fire on that – the Royal Scots were certainly at a disadvantage. Eventually they were able to set up a bombing post that allowed some troops out to advance to a nearby wall to form a new line of defence, but when their remaining Lewis gun was destroyed they had little choice but to gather up their dead and injured and retreat behind another wall and attempt to hold that.

The action on the 24th November had not been successful but was not futile either. Once reinforcements arrived the Royal Scots were withdrawn from the front line and relieved for a time and other battalions in Allenby’s army carried on the attack, with Nebi Samwil eventually falling on the 9th December and Jerusalem was captured on the same day, though needless to say, I am cutting a long and complicated story short in summarising Allenby’s campaign this way. Private John Mathieson Brown was not to see any of this though. His records don’t state whether he was in the 7th Royal Scots’ 1st Company or the 4th, only that he was killed in action on the 24th November and is now buried in the Jerusalem War Cemetery in Israel.

Sources: Major John Ewing, M.C. “The Royal Scots 1914-1919”, Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh, 1925

Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, “The First World War”, Cassell, London, 1999

John D. Grainger, “The Battle for Palestine 1917”, Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2006

War Graves Photographic Project

And of course, Garry Ketchen for the preliminary genealogy work and his permission to use it.