By Henry Noltie & Mark Watson (continued from Part III)

Military Men, Society Ladies and the French

The Army Officers

The violence inflicted upon India by the EIC army has been rightly and loudly condemned, but this should not obscure the fact that at least some of its officers were intelligent men who made notable contributions to the study of many aspects of Indian culture and natural history. Nine such officers, collectively, are responsible for a total of 110 specimens in the Herbarium. As with the other groups of contributors it seems appropriate to discuss their collections geographically.

The Western Himalaya (ii)

As explained in Part II, the period of assembling the Herbarium followed close on the heels of the conclusion of the Gorkha War, and therefore with extensive military and related activities in the Western Himalaya – not least surveying. The collections from this region made by the Garden’s Plant Collectors and by medical officers have already been discussed (in Parts I and II respectively), but the region also represents the biggest single origin for botanical contributions from military personnel.

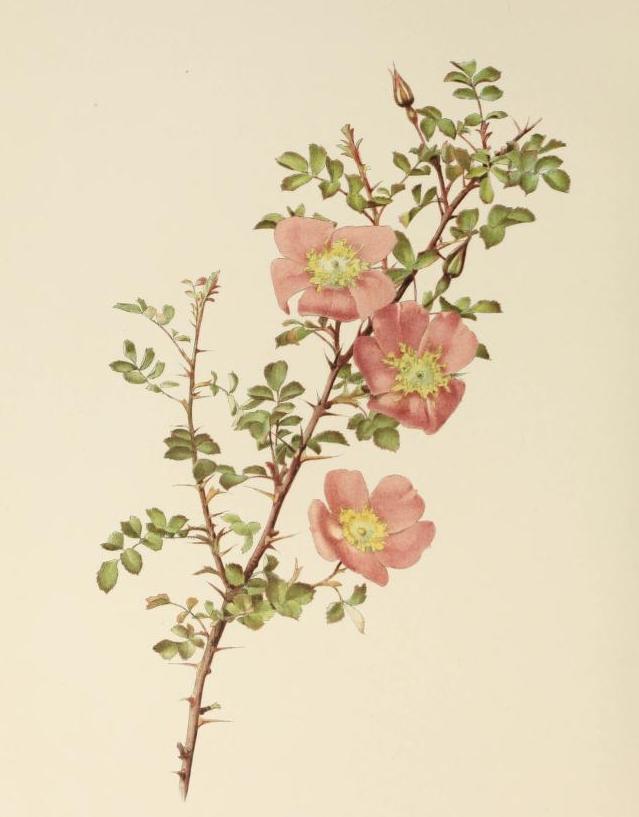

Of these the most active (66 collections) came from William Spencer Webb (1784–1865). Webb became an Ensign in the 56th Bengal Native Infantry in 1801, was promoted to Captain in 1818, and retired in 1824. Much of his career was spent in undertaking surveys, during which he assisted Blinkworth and Kamrup in their collections for Wallich (see Part I). The majority of Webb’s specimens are from Sirmur, but five come from as far afield as Chinese Tartary. The specimens were clearly highly valued by Wallich, who intended to name species for Webb in the genera Lonicera, Leucostemma, Rosa and Silene. Among those still recognised is the beautiful rose Rosa webbiana.

James Gerrard, the medical member of the remarkable Aberdeen family, has been discussed in Part II; it is now time to turn to his military brothers: Alexander (1792–1839) and Patrick (1794–1848). The pair were distinguished by Wallich by their military titles at the time of their botanical collections in the mid-1820s, as Captain and Lieutenant respectively; each contributed 16 collections, nearly all from Sirmur. Alexander joined the 13th Bengal Native Infantry as an Ensign in 1808 and was promoted Captain in the 27th Native Infantry in 1825.

He was commissioned to undertake many surveys for the army and on one in 1817, with Dr George Govan, he travelled from Sabathu up the valley of the Sutlej. The 1818 survey was with his brother James, to Spiti, who again accompanied him in 1821 on an unsuccessful attempt to reach Lake Mansarovar in Chinese Tartary. Alexander retired in 1836 and returned to Aberdeen, where he died in 1839. Patrick Gerrard joined the 8th Bengal Native Infantry in 1812, served in the Gorkha War in 1816 and was promoted to full Captain in the 9th Native Infantry in 1828. In 1821 he took part in a survey with his brother Alexander, was invalided in 1832 and spent the rest of his life in Simla, where he died in 1848.

The genus Colquhounia was named by Wallich for Sir Robert David Colquhoun (1786–1838), the best known member of which is the scarlet-flowered, bird-pollinated shrub C. coccinea. However, as in Scotland the surname is pronounced ‘Cahoon’, it is a moot point as to whether the tongue-twisting Latinised form should be pronounced Cahoonia, or ‘Col-kew-hoon-ia’. Born in Edinburgh in 1786, as a ‘younger son’ Robert in 1807 enlisted with the EIC to become an Ensign in the 22nd Bengal Native Infantry. However, following the death of his older brother in 1812 he became the 11th Baronet of Tullyquhoun.

In 1815, during the Gorkha War, Colquhoun raised the ‘Kemaoon’ Battalion, later the 3rd Gorkha Rifles (The Kumaon) Regiment, which uses his tartan and which he commanded until 1828. Later postings were in Calcutta, which in 1831 included the supervision of the surviving members of the family of Tipu Sultan, who had been exiled from Mysore to Bengal. It was from Kumaon that Colquhoun sent three specimens to Wallich that are in the Herbarium – a fern (now Selliguea capitellata), Cornus capitata and Quercus semecarpifolia, though none of the three then known species of the genus that bears his name.

The Persian Gulf

Then, as now, relations between Britain and the Middle East were complex and in Wallich’s time involved the EIC both politically and, given the position of Bombay as the Company’s major port on the west coast, practically. For this reason there are five specimens in the Herbarium from the region (from the present-day countries of Iran, Iraq and Oman). Of these four certainly, and one possibly, were contributed by army officers, one of whom emerges as one of the most interesting of all Wallich’s correspondents.

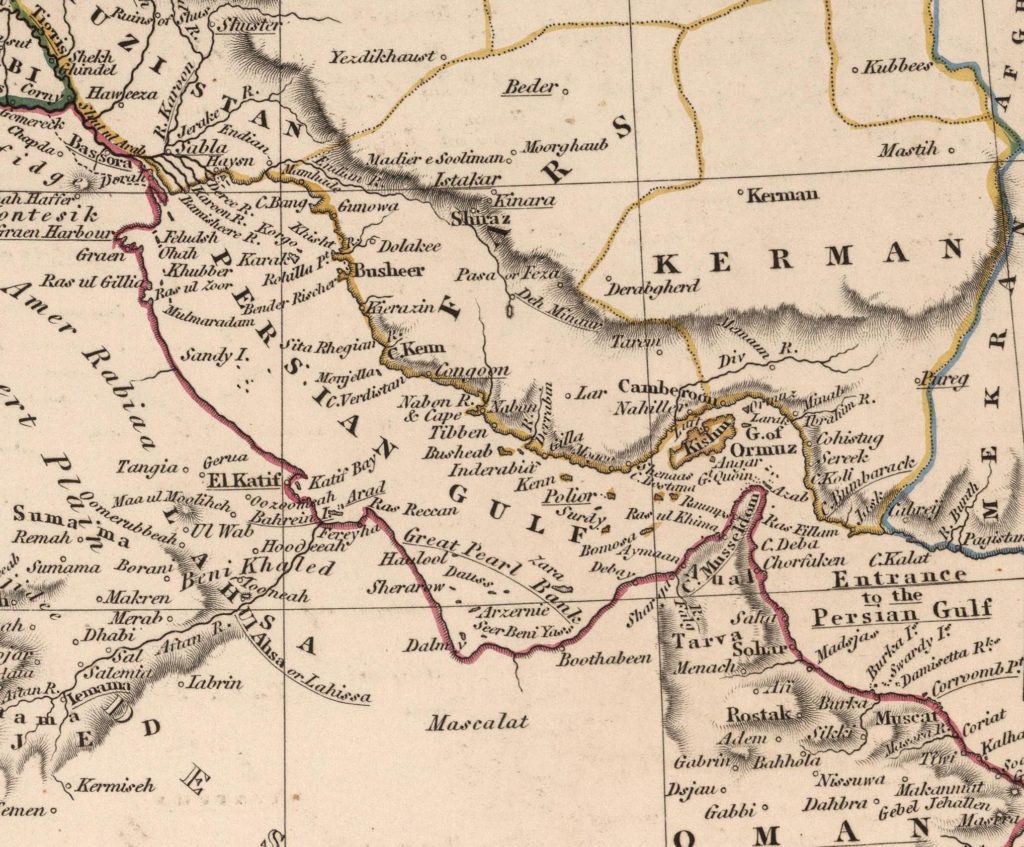

Robert Taylor (1788–1852) started as a soldier in 1803 with the 3rd Bombay Native Infantry, but must have shown diplomatic skills as from 1807 to 1818 he held positions in the Residency at Bushire (now Bushehr), a port on the coast of what is now Iran, where, since 1763, the Qajar Dynasty of Persia had allowed the EIC a trading base. In 1818 Taylor was transferred to the Residency at Bussora (now Basra), the port on the Shatt el Arab then part of the Ottoman Empire. Ten years later Taylor moved the Residency to Baghdad where he remained until 1847 with his wife, the Armenian Rosa Mosco, whom he had married in Bushehr.

Taylor became a considerable scholar and collector; his Oriental manuscripts and the ‘Taylor prism’ (an hexagonal clay tablet with cuneiform inscriptions of Sennacherib’s campaigns) are now in the British Museum. Taylor’s brother James was a Calcutta merchant, which might account for the link with Wallich, and of Taylor’s five specimens three are from Bushehr, one from Basra, and one from Muscat.

The origin of the fifth Middle Eastern specimen in the Herbarium, ‘Sophora Houghiana’ (now S. mollis) from ‘Persia’, is unclear – its sender is denoted merely ‘Dom[inus] Hough’, with no distinguishing initials. One possibility is Robert Hunter Hough (1778–1830) who, as Military Auditor-General of Bombay, could conceivably have had connections with Persia and seems more likely than (as previously speculated) the American Serampore-based missionary George Hough who has no known Persian connections.

Nagpur

Doubtless due to its remoteness from the three coastal metropolises, Central India was one of the last parts of the Subcontinent to be explored botanically, and even now its flora is relatively poorly known. At its heart lies what was the Maratha Kingdom of Nagpur, which, following the Third Anglo-Maratha War, became a Princely State in 1818; a Resident was installed, and the Nagpore Subsidiary Force established to protect the Raja. It was probably in connection with this that Lieutenant John Anderson Barstow (1796–1863) of the 18th Bengal Native Infantry was in Nagpur in 1824.

From there Barstow sent a plant to the Calcutta Garden to which, while uncertain of its genus, Wallich gave the epithet ‘callosa’; Nees von Esenbeck took up the epithet and the plant is now Strobilanthes callosa. A large shrub of the family Acanthaceae it covers large areas of the upper slopes of the Western Ghats, especially in the State of Maharashtra, which it turns purple when it flowers en masse every seven, eight or ten years. As the plant is by no means exceptional when not flowering one wonders if Barstow had been told of its unusual life cycle and that it was on this account that he sent it to Calcutta. It flowered there in 1827, when the specimen was made for the Herbarium.

Assam

Following the Anglo-Burmese War, as already noted in Part III, Assam became part of the EIC territories – and an increasingly important one. One of those responsible for the region’s development was Major General Francis Jenkins (1793–1866), who started his Indian career as an Ensign in the 24th Bengal Native Infantry in 1811. From 1834 until his retirement in 1861 he held the post of Commissioner of Assam and played a major role in the establishment of the tea industry. From his earliest days in Assam Jenkins had corresponded with Wallich but, though he was a major supplier of plants for the Calcutta Garden, only a single specimen (of what is now Lithocarpus elegans from Chittagong) found its way into the Herbarium.

Malacca

William Farquhar (1774–1839) was last seen in Part II accompanying Raffles to Singapore in 1819, where he stayed on as first Resident of the emerging settlement. The relative roles of the two men as ‘founders’ of modern Singapore became a matter of unfortunate dispute, and it is certainly unfair that it is only Raffles’s role that should be remembered and that, other than to historians, Farquhar’s has been forgotten. His single contribution to the Herbarium, however, dates from his previous posting. Farquhar was born at Newhall, near Stonehaven, and went to Madras in 1791 where he was commissioned into the Madras Engineers.

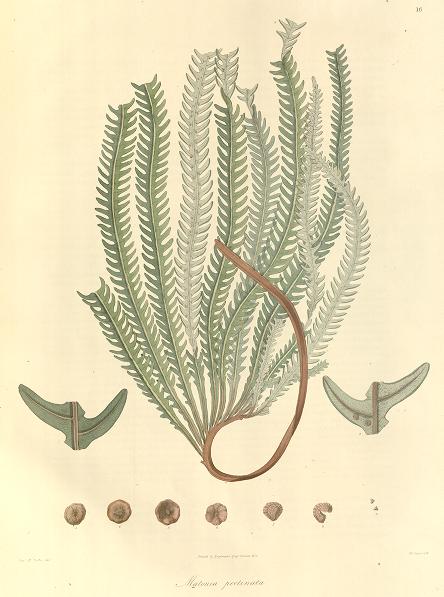

In 1798 he crossed the Bay of Bengal to Malacca, where his organisational and diplomatic skills were recognised and where, from 1803 to 1818, he was Resident. While at Malacca he commissioned Chinese artists to make a large collection of natural history paintings (now in the National Museum of Singapore), an example later followed by Raffles. It was also from Malacca that Farquhar collected an unusual fern on Mount Ophir. It was sent to Wallich who intended to name it ‘Prionopteris Farquhariana’, but when formally described by Robert Brown it was called Matonia pectinata. Farquhar retired to Perth, where he married and fathered six children, having earlier had six with a Malay wife.

The Ladies

Among Wallich’s large number of correspondents are at least 17 women (six of them titled, four writing from within India), mainly with interests in botany and gardening (though one was a wax-flower modeller). This correspondence, however, resulted in only five specimens for the Herbarium.

Diana Beaumont (1765–1831) was the owner of estates in Yorkshire and Northumberland, which, despite her birth on the wrong side of the blanket, she inherited from her father Thomas Wentworth. She lived and gardened with her husband Colonel Thomas Beaumont mainly at Bretton Hall in Yorkshire. Its grounds are now the Yorkshire Sculpture Park where her handsome Camellia House survives, though her once-famous domed conservatory has long gone.

Mrs Beaumont sent many plants to the Calcutta Garden and, as with many other aristocratic British garden owners, Wallich responded in kind with plants in exchange; in this case an additional reward came in his naming of the genus Beaumontia, a beautiful climber of the family Apocynaceae, with large, tubular white flowers. The single ‘Beaumont’ specimen in the Herbarium is a legume that grew in the Calcutta Garden sent from Bretton, but of unknown geographical origin. It was named ‘Cassia fulgens’ by Wallich, and is now (under the name Senna multijuga) known to be native to Mexico and tropical South America, though it is now widely cultivated in the tropics.

Wallich had had good relations with the Marquess of Hastings (Governor-General 1817–23) and his wife Flora, the (Scottish) Countess of Loudon, and both husband and wife had serious botanical interests. Hastings’s successor was Lord Amherst whose much older wife, curiously, was also a Countess, though of the dowager variety. Amherst’s diplomatic career was an unfortunate one: his kowtow-free embassy to China in 1816 had been a disaster and his Indian Governorship was blighted by the Anglo-Burmese War. Admittedly he had been somewhat unwillingly been forced into this conflict, but it shortened his Governor-Generalship, which he held only from 1823 to 1827.

Lady Amherst (née the Hon Sarah Archer) (1762–1838), was interested in natural history and a competent artist (traits both passed onto her eponymous daughter, also a Wallich correspondent), and wrote to Wallich about botany. She is best remembered for the colourful pheasant that bears her name, a native of south-west China and northern Burma, of which a pair reached her (indirectly) from the King of Ava, as part of the peace settlement at the end of the Burmese War. She was commemorated by Wallich in a comparably spectacular plant, Amherstia nobilis, with dangling racemes of orange-red flowers that resemble dancing Chinese characters, first shown to him in a Burmese monastery garden. In 1827, shortly before the Amhersts left India (he had been given an earldom, and somewhat surprisingly taken the designation ‘of Arakan’), the couple visited Simla, where Lady Amherst met George Govan and sent four specimens to Wallich, two of which still bear her name: Wulfeniopsis amherstiana and Bosea amherstiana.

The French

Long before his visit to London in 1828 Wallich had been thoroughly integrated into British life in Calcutta, but it should never be forgotten how far he had travelled from his Jewish origins in Denmark to get there. His cultured European background gave him the advantage of a broad outlook and many skills, not least of which were linguistic. Even his earliest letters in English are faultless and idiomatic; he also corresponded in German, Danish, and French.

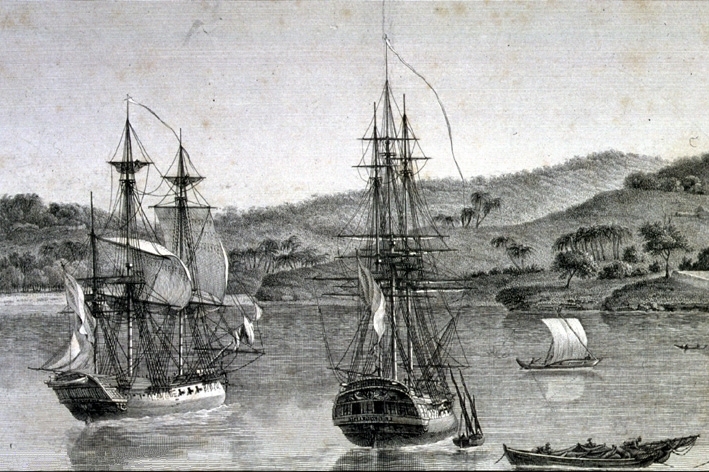

17 specimens in the Wallich Herbarium result from two French correspondents – one based in India, Jean-Baptiste Louis Claude Theodore Leschenault de la Tour (1773–1826), the other, Pierre-Bernard Milius (1773–1829), in Mauritius. Coincidentally, and long before their contact with Wallich, both had taken part in Nicolas Baudin’s voyage to Australia – Leschenault as one of the botanists, Milius as second in command of the Naturaliste who, in 1803, had sailed the senior ship the Géographie back to France from Mauritius following Baudin’s death there. Both botanist and naval officer would return to the East: Milius as Governor of the island of Bourbon, a post he held from 1818 to 1821, and Leschenault in 1815 to establish a botanic garden in the French colony of Pondicherry on the Coromandel Coast of India.

Only a single specimen in the Herbarium (what is now Eugenia buxifolia) was sent by Milius from Mauritius; Leschenault’s contributions were more significant. Botany, as so often, allowed the vaulting of diplomatic hurdles and, through the intervention of Sir Joseph Banks, the EIC allowed Leschenault to travel in South India, just so long as he didn’t ‘intrigue with the Natives’. He thus became one of the earliest botanists to discover the riches of the Nilgiri Hills, where Ootacamund would soon be developed as the major hill station for the Madras Presidency, and affectionately known as ‘Ooty’. All 16 of Leschenault’s specimens in the Herbarium are from the Nilgiris, of which Wallich intended to name five for him (though none of these are currently accepted).

Sudhir Chandra

In these 4 parts I missed Silvaea Hook. & Arn. 1837 . Euphorbiaceae. M. (Mister ?) De Silva; collect: for Nathaniel Wallich; epon: Silvianthus Hook.f. 1868 (Carlemanniaceae); biogr : Burkhardt 2018

I need infomation on the De Silva honoured for my Dictionary of Commemorative Plant Generic Names,Publ. Letters A -R vols 1-38, 1992, 2012 by Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehra Dun, India

Sudhr Chandra

Andre Trombeta

Silvaea and Silvianthus are named after Francis de Silva, botanical collector

See in stories.rbge.org.uk/archives/3472

Andre Trombeta

Silvaea and Silvianthus are named after Francis de Silva, botanical collector

See in stories.rbge.org.uk/archives/34728