RBGE has been a place that I have visited since I was little, with my parents, with friends or often by myself. It’s a place where one can forget they are in a busy city, as the gardens have a level of tranquillity and peace rarely found so close to the centre of a capital city. Seeing the garden transform with the changing seasons is one of my favourite aspects, personally it has often served as a seasonal reminder that no matter what one is going through, the natural world will not stop for us, seasonal cycles will continue, and life goes on. There’s a powerful sense of beauty in that, which is why protecting our natural world is of the upmost importance.

Having just graduated from a BSc in Biology, I learnt the importance of conserving our natural environment and a month’s placement at RBGE last summer showed me an insight into the kind of conservation work that RBGE carries out, not just in the gardens themselves but also behind the scenes. I spent a week in the Nursery working under Rebecca Drew’s supervision on the Scottish Plant Recovery Project, a project which seeks to conserve Scottish native species within the nursery and then preserve and grow natural populations of rare and threatened native plant species right across the country. I was lucky enough to be taken out into the Pentlands to survey the native Yellow Marsh Saxifrage (Saxifraga hirculus), a species which due to overgrazing from sheep and changes in natural landscapes is extremely threatened in Scotland. Crouched down within the hills, with at times a magnifying glass in hand, trying to identify this elusive little plant, I remember thinking what a great job this would be, out in the big outdoors trying to save species from the devastating impacts of unsustainable human activity.

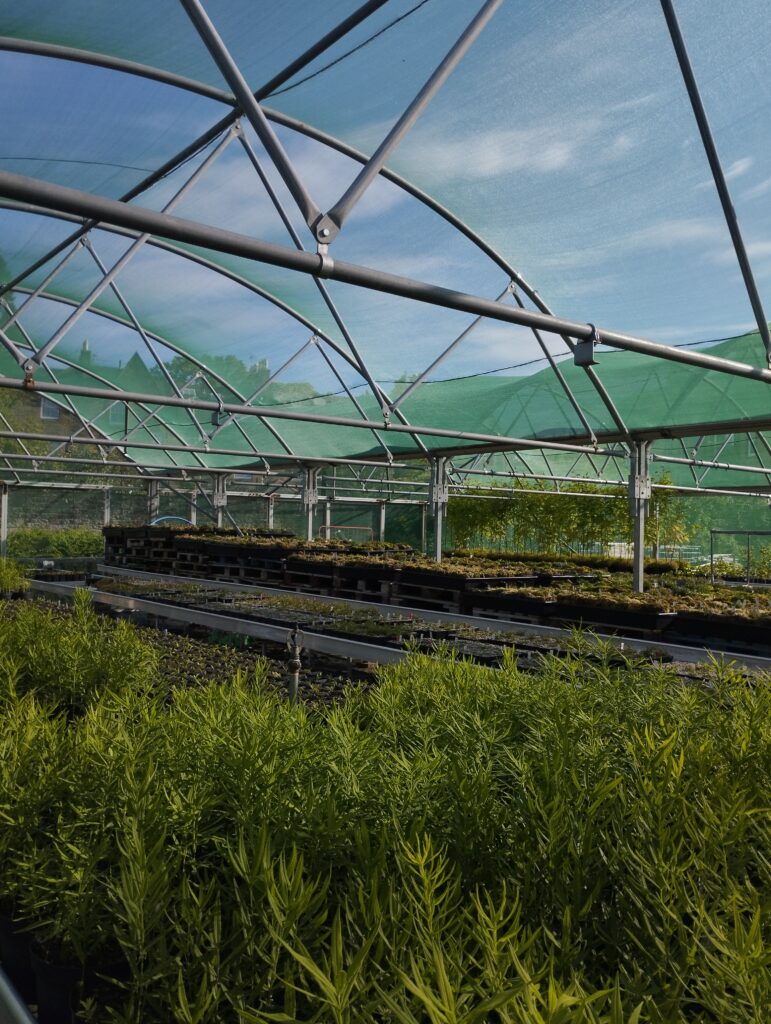

Fast forward a year later, I am now part of the RBGE Scottish natives team and what a first month it’s been. I think a workplace that has members of staff that stay for decades with such a high level of dedication to their job, tells much of the nature of the job and the healthy environment found at RBGE. Everyone has been so welcoming and supportive but also given me the freedom to learn independently which at these early stages of a career can be equally important. Every day, I am surrounded by people that have a deep horticultural understanding, an impressive collection of Scottish natives and (so far) relatively clear sunny blue skies.

As the plant recovery project finishes at the end of March 2026 we are now at the stage of tending to our collection within the nursery and organising suitable translocations. Within the plant recovery project, the 10 species of threatened Scottish natives all have their own respective ecological challenges that we need to tend to in the Nursery, giving them the best fighting chance for successful translocations out into the field in the coming months. From patiently weeding with tweezers the delicate little oblong woodsia (Woodsia ilvensis), to ensuring the specific requirements of the cascade are met for the Yellow Marsh Saxifrage , my weekly jobs are diverse and fulfilling as I genuinely feel like the work we do here is making a positive difference that gives some hope for the natural Scottish environment. A very rewarding aspect of the job is when we carry out tours of our specimens for different enthusiastic visitors that all seem to leave intrigued about the project and often ask to be kept up to date on how it progresses.

The group of species that has taken my particular interest in this project is the Hedlundia complex, endemic to an island on the west coast of Scotland which is often referred to as “Scotland in miniature”. The Isle of Arran is home to one of the rarest trees on Earth, Hedlundia pseudomeinichii aswell as the endangered Hedlundia arranensis and Hedlundia pseudofennica. You can read the ins and outs of this complex here. It fascinates me that Arran’s complex of endemic Hedlundia’s have created a perfect picture of evolution right here in Scotland yet there is relatively little publicity about this trio of species. What intrigues me even more is that from a conservation perspective it poses a very interesting dilemma. One could argue that Hedlundia pseudomenichii was an accident, an evolutionary deadend and we should just let nature play out, that conducting a mass planting of these rare species shifts our work from conservation into gardening. I believe this is true, we should let nature play out, but I also believe that in order to let nature play out we need to give it a bit of breathing space from our human impact. Earlier this year, Arran’s Glen Rossa, was victim to a catastrophic wildfire that wiped out 27,000 trees and 10 years of conservation work. Natural disasters will unfortunately become more regular as our climate changes therefore it is our responsibility to focus on giving our already threatened species the best chance possible. I’m very excited for the what lies ahead in my time on the project as I truly believe our work will help conserve the future of Scottish native flora.

This project is supported by the Scottish Government’s Nature Restoration Fund, managed by NatureScot.

Instagram @rbgescottishplants

X @TheBotanics

X @nature_scot

X and Facebook @ScotGovNetZero

Facebook @NatureScot

#NatureRestorationFund