The naming after white men of plants from remote parts of the world has now come to be seen as reprehensible, so it’s time to ‘fess up’. Two plants bear my name, but both came about when a genus was subsumed into an earlier one, followed by the application of a nomenclatural rule that disallows the creation of a ‘homonym’ (a binomial identical with one previously published for a different plant). Were this to happen the plant must be given a ‘nomen novum’ – a new name based on the same material (‘type’) as the one it replaces. Both of my ‘eponyms’ are of this sort and made without my prior knowledge. However, as one is an obscure sedge and the other a miniscule lily less than a centimetre in height, both more familiar to Himalayan yak than to human beings, I hope to be excused from accusations of vainglory.

One of the genera with which I had to deal when writing accounts of petaloid monocots for the Flora of Bhutan in the 1990s was Lloydia. The original member of the genus was first found on the highest rocks of Snowdon (now Eryri) by Edward Lhuyd (aka Lloyd or Lhwyd) (1660–1709), Keeper of Britain’s first public museum, the Ashmolean in Oxford. Lhuyd supplied information about the plant to his friend John Ray who in the second edition of his Stirpium Methodica Stirpium Britannicarum (1696) called it ‘Bulbosa alpina juncifolia’; in the third, posthumous, edition (1724) it was illustrated by J.J. Dillenius.

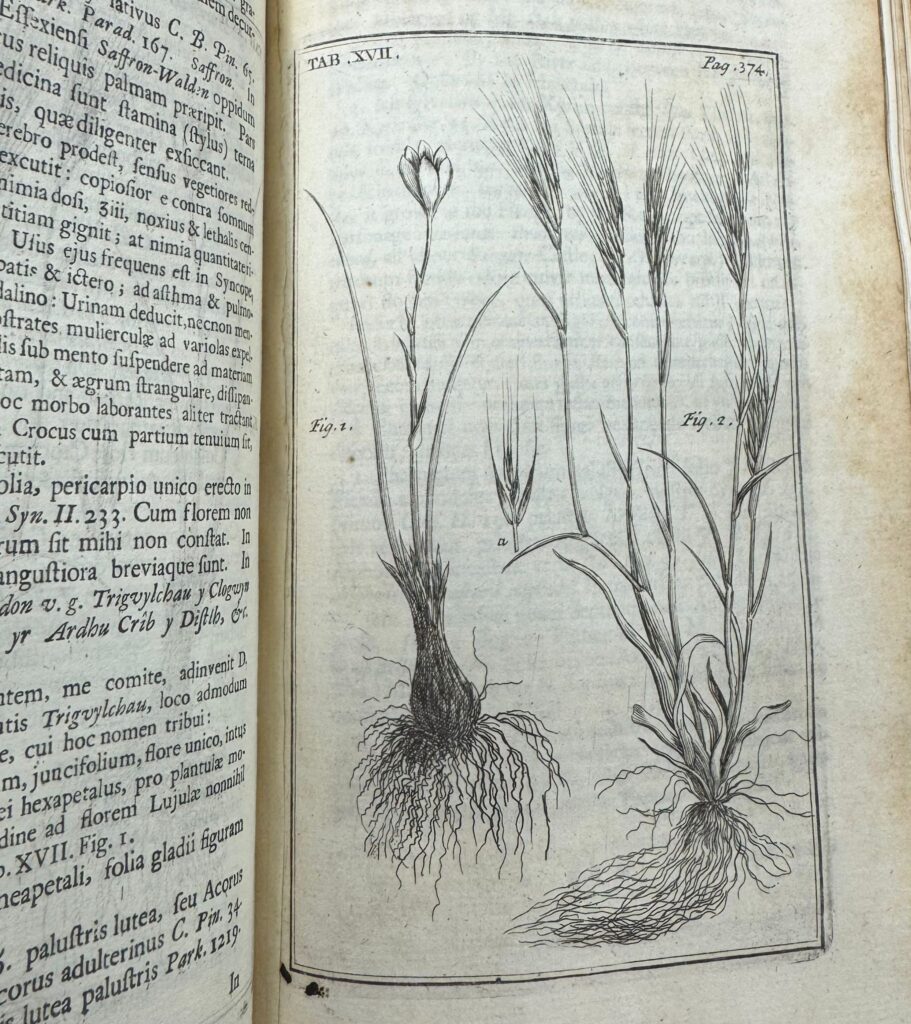

Dillenius’s engraving (1724)

L. serotina on the Beima Shan

Though in parochial Britain the plant became known as the Snowdon lily its distribution is circumboreal and when Linnaeus gave it the binomial Bulbocodium serotinum in Species Plantarum (1753) he cited not only Ray but several earlier descriptions and phrase-names. All but Ray’s ultimately go back to Caspar Bauhin, who first described the plant in 1620 from the Swiss and Austrian Alps as ‘Pseudo-Narcissus gramineo folio’. It flowers in summer, so Linnaeus’s epithet, meaning ‘late flowering’, though presumably intended in contrast to spring-flowering bulbs doesn’t make sense as there are many autumn-flowering bulbs. The genus was first named by Richard Salisbury in 1812 to commemorate Lhuyd. Salisbury gave no generic description but one was provided by H.G.L. Reichenbach in 1830 when he combined it with the earliest available epithet to make Lloydia serotina (L.) Rchb.

In the Sino-Himalaya as well as typical L. serotina, looking much as it does on Snowdon or on the Beima Shan of Yunnan, a tiny form, only a few centimetres high, is found at very high altitudes between Kumaon and Yunnan. This was described in 1929 as L. serotina forma parva and later raised to varietal rank.

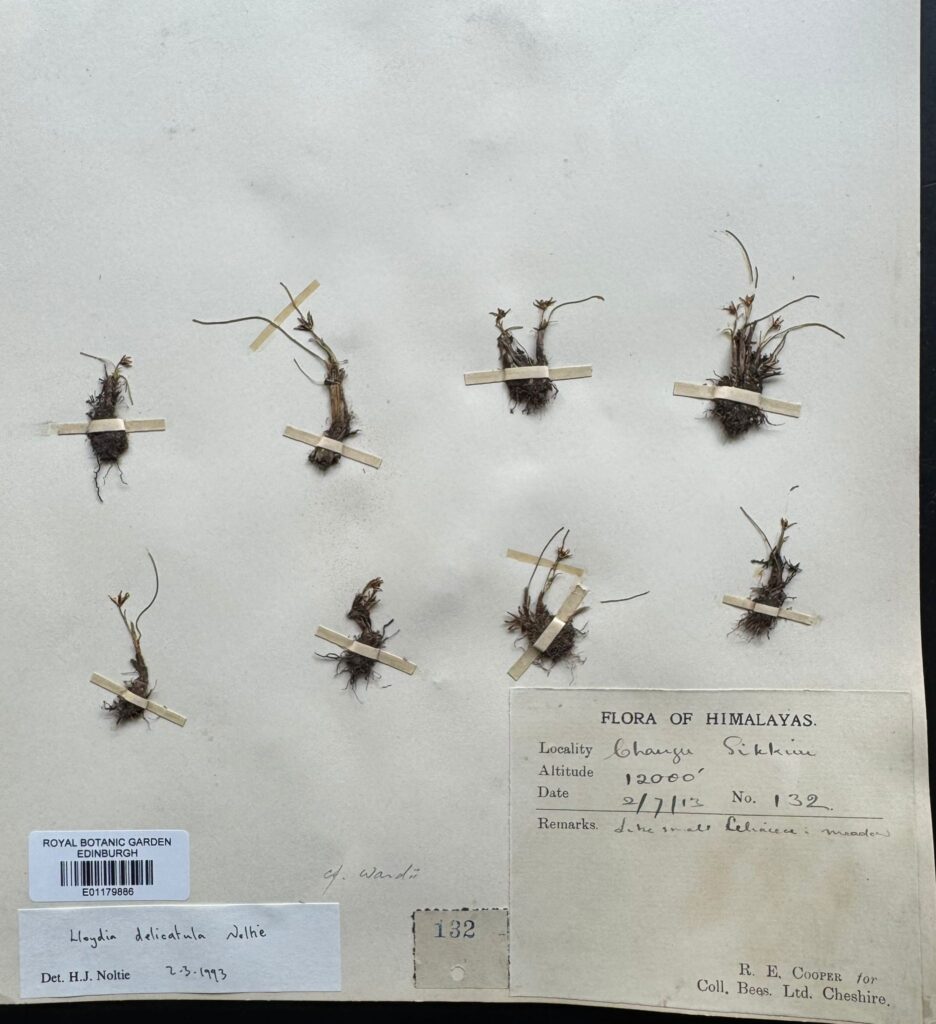

Type of L. serotina var. parva.

L. serotina var. parva, Lasha Chhu, N Sikkim

Close examination of the flowers of herbarium specimens of dwarf alpine specimens from the Eastern Himalaya showed some to differ from var. parva in tepal shape and nectary position, and therefore worthy of specific recognition. Like many ‘new’ species it was therefore first ‘discovered’ in the herbarium – from specimens collected long ago from localities between Central Nepal and NE Bhutan at altitudes of 3600 to 4600 metres. It was Joseph Hooker who made the first collection in 1849 on his momentous expedition to Sikkim. Several later collections were made in Sikkim, including by R.E. Cooper in 1913; in Bhutan a single collection was made by Ludlow, Sherriff & Hicks in 1949; and in Nepal several, of which the earliest was made in 1935 by a local collector for F.M. Bailey. While William Wright Smith recognised the distinctness of the diminutive plant in 1910 he gave it only an unpublished, informal name ‘var. sikkiminesis minima’. For its delicacy and diminutive stature I decided on the name Lloydia delicatula.

L. delicatula, Cooper specimen, Sikkim, 1913

At this point, in July 1992, with colleagues David Long, Ron McBeath and Mark Watson, I was fortunate to visit western Sikkim on the ESIK expedition. Here are the relevant extracts from my diary of that somewhat gruelling monsoon trip.

Bikbari. 13 July 1992, 6.50 pm

The best plant seen today was Lloydia yunnanensis of which David had found a single specimen yesterday; he also found today’s as it inhabits mossy places – beautiful, elongated white bells, closely related to the Snowdon lily (L. serotina). Even prettier are the nodding yellow flowers (with a brownish-red spot inside) of L. flavonutans, which lives in Kobresia turf. David went on a bit further than Mark or me and found my miniscule species L. delicatula. Provoking not to see it growing for myself, though expect we will see it again later. At least I could examine it in detail and confirm the position of the nectaries, which distinguishes it from L. serotina var. parva. Coming down we saw a giant snipe and a beautiful form of Meconopsis simplicifolia with pure white petals, contrasting strikingly with the golden stamens.

L. flavonutans, Bikbari, 4300m.

L. yunnanensis, Bikbari, 4150m.

Chaunrikhiang, 4500 metres. 14 July, 5.50 pm

Gradual slog up to this Base Camp, could hardly put one foot in front of the other – this really is my upper altitude limit. Eventually made it here – a picturesque group of buildings including a giant, aluminium-clad sausage roll, apparently a medical hut. The others are mainly stone built and the settlement can apparently accommodate up to 200. We are in a large, grim building with a giant row of bunks divided into eight, six-foot sections – very barrack-like. Outside is a helipad for army helicopters. Weather very good all day – no rain while we were walking, but mist and rain caught up just as we arrived. Magnificent views when it lifted – we are cradled in the very middle of the towering peaks seen from last night’s camp – serrated, knife-edge ridges, the spectacular jagged pyramid of Frey Peak, the massive twin summits of Forked Peak, its upper part with finely wind-fluted, gleaming white ice, the lower slopes with dramatic ice cliffs. After a snooze (the others, fortunately, were equally tired) we went up towards the Ratong Glacier – an almost mystical experience. The mist like a veil, rising and falling, animating the bleak landscape. Stunning colours and textures – a tiny, still green pool, wonderful stone piles, an eerie wooden cross worthy of Caspar David Friedrich, its horizontal limb made of an old ski, fantastic braided streams issued from the glacier, strewn with rocks and flats of silver gravel. All of this enclosed between two steep lateral moraines. Among all this wildness, with the giant peaks looming above and occasionally picked out by spotlights of sun, a silver path of finest gravel threaded its way adding a human element and the enticement of something to be followed. With the mist down the scale becomes intimate and particular objects (such as the cairns) leap into focus; when it lifts the grander scale becomes apparent and the objects become insignificant compared with the vast majesty of the landscape.

Monocot news: Lloydia delicatula is growing in the short turf all around the Base Camp, so I see it myself for the first time in the living state, confirming what I recognised as a distinct species from herbarium specimens.

L. delicatula, Chaunrikhiang, 4500 m.

15 July, 5 pm

The yak and yaklets came placidly grazing by. A boy later came to round them up to be milked – they must be taken back to the encampment down below for the night, but one of two got left behind and started making their funny grunting noises (Bos gruniens). The huge flock of choughs wheeled around the camp and a hoopoe put in a surprising appearance.

I spent ages digging up some of the Lloydia for living and herbarium specimens – it really is minute, only a centimetre of it showing above ground [it didn’t survive in cultivation].

Having seen the plant in the field I felt confident to publish it the following year (1993), with notes on some other members the genus, in the Edinburgh Journal of Botany.

By this point the genus Lloydia had about 20 recognised species, but in 2008 a molecular study (for which I was able to supply dried Sikkim material not only of L. delicatula, but L. yunnanensis and L. flavonutans) showed that it shared a recent common ancestor, and was therefore ‘monophyletic’, with the genus Gagea. The genus Gagea was not only much larger (c 250 species) but had been published earlier, in 1806, also by Salisbury. The name commemorates another white man, Sir Thomas Gage (1781–1820) of Hengrave Hall, Suffolk, mainly known as a lichenologist.

It would take many years for all the epithets to be transferred from Lloydia to Gagea but in 2008 an international team of Lorenzo Peruzzi from Pisa, Jean-Marc Tison of L’Isle d’Abeau, and Angela and Jens Peterson from Halle made a start, with the transfer of three of them (L. serotina already had a name in Gagea, showing the always problematic distinction between the two genera). Of the three one was L. delicatula but there was a problem: there was already a Gagea delicatula, described by Alexei Vvedensky from Uzbekistan in 1941.

A new name therefore had to be made, which is how Gagea noltiei came about.

David

Much enjoyed and I can just about remember seeing your plant, of course small lilies can be just as beautiful as Cardiocrinums. Happy memories!