“Excursions may be truly said to be the life of the botanist. They enable him to study the science practically, by the examination of plants in their living state, and in their native localities; they impress upon his mind the structural and physiological lessons he has received; they exhibit to him the geographical range of species, both as regards latitude and altitude; and with the pursuit of scientific knowledge, they combine that healthful and spirit-stirring recreation which tends materially to aid mental efforts. The companionship too of those who are prosecuting with zeal and enthusiasm the same path of science, is not the least delightful feature of such excursions. The various phases of character exhibited, the pleasing incidents that diversified the walk, the jokes that passed, and even the very mishaps or annoyances that occurred – all become objects of interest, and unite the members of the party by ties of no ordinary kind”. (Balfour 1848 cited in Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 1848: 122)

As is clear from his writing in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, Balfour’s thoughts toward the necessity of fieldwork went far beyond the requirement of collecting plant specimens. Balfour considered the excursions a critical part in the education of students attending his botanical classes. Between 1852 and 1872 Balfour kept extensive excursion diaries, meticulously recording locations visited, times and forms of transport used, members of the botanical parties, plants collected, geological and antiquarian novelties and amusing and noteworthy anecdotes.

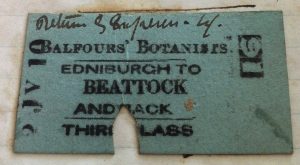

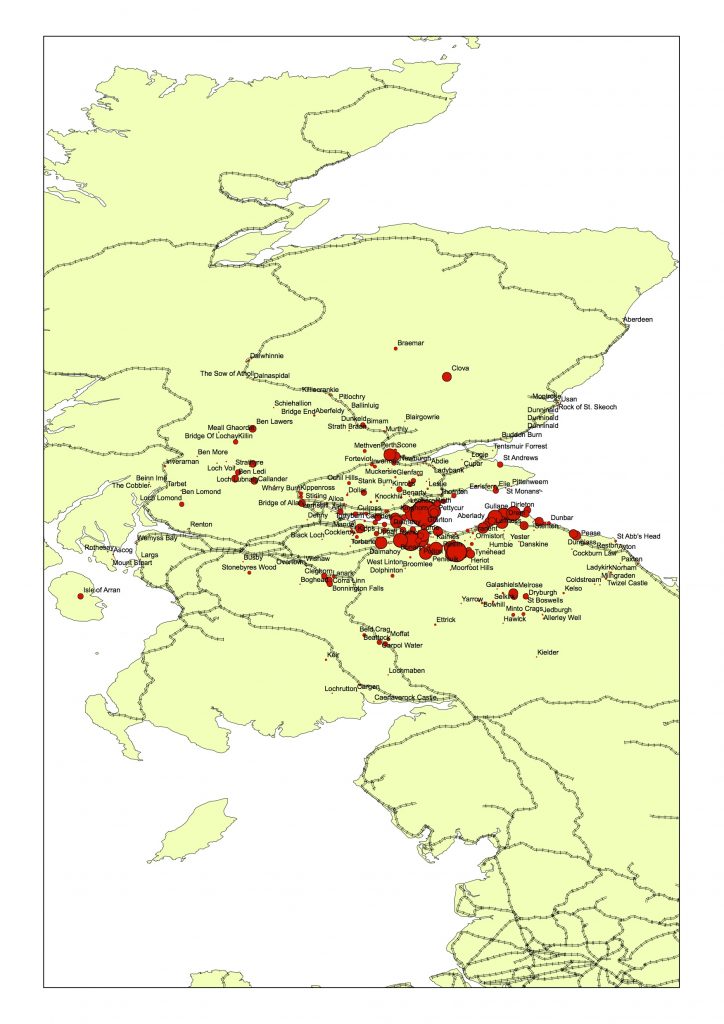

On each Saturday of the summer session (May to the end of July) Balfour conducted day-long botanical excursions to various sites across Scotland and occasionally into northern England. On such days it was common for Balfour to be accompanied by any number between 25 and 200 students. Largely the student body consisted of pupils from Balfour’s botanical classes but fairly frequently the students from the botanical class were joined by students and professors from the Natural History and Geology departments, students from the School of Design, members of amateur natural history societies, members of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh and on occasion RBGE garden staff. As the century progressed the day-long excursions relied increasingly heavily on the developing rail network to conduct botanical parties across a large proportion of Scotland and Northern England, often at a discounted fare.

Towards the end of the summer session, after the Saturday excursions had ceased, an excursion of longer duration (approximately three days) would be undertaken. Around thirty students would accompany Balfour to, most frequently alpine locations, such as Glen Clova, the Isle of Arran and Loch Lomond. Common practice included long, hard days of botanising, observing and collecting, and overnight accommodation of variable levels of comfort. In 1850 Balfour recorded in his diary “Reached Clova at 11pm. Had tea at Clova and were accommodated with straw beds on the floor of the large hall lately built for the games which are held in Clova in August. Twenty five slept on the floor, the remainder in the old inn, partly on beds and partly on the floor. Sleep much disturbed in the hall by noisy and restless members of the party, some had scarcely two hours’ sleep” (Balfour 1850).

In the month of August an excursion of extended duration would be conducted with Balfour and a few students, on average numbering no more than fifteen, and occasionally friends and relations of the Balfour family. Frequently combined with Balfour’s summer holiday, such excursions lasted between ten days and several weeks. The botanical party would engage in exploring botanically rich areas of the Scottish highlands such as the Angus Glens, Braemar and on occasion locations abroad such as Switzerland (1858) and Northern Italy (1861).