In the 1873 Guide to Edinburgh Botanic Garden the classroom is described as follows: “The large room is seated for about 300 students, with arrangements for showing living specimens in pots, dried specimens from the herbarium, large drawings, and minute structures under microscopes. A class Herbarium, illustrating genera and species arranged according to the natural orders, is kept in the room for consultation” (Balfour 1873). Recalling the lecture room of his father, Isaac Bayley Balfour wrote “His lecture table became a synopsis of the lecture – living plants, herbarium material, museum specimens all were pressed into service to elucidate the points of the discourse, whilst the walls were tapestried by diagrams. Never did a teacher more sedulously absorb the new for presentation to his pupils” (Balfour 1913).

The Visual Value of Wall Charts

By the mid nineteenth century, wall charts had been introduced across Europe as an approved teaching approach for the instruction of Biblical History, Geography, History and Natural Science. Originally a German concept and initially limited to classrooms in German speaking countries, wall charts rapidly found favour enjoying a ‘golden age’ between 1870 and 1920.

Under Balfour’s directive the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and The University of Edinburgh jointly, had over twenty sets of Wall charts. Distinction needs to be made between printed and published wall charts and those that Balfour commissioned – hand drawn specifically to complement his teaching objectives.

The printed and published wall chart collection contained:

- German Wandtafeln (Wall Diagrams), some sets comprising over 100 diagrams

- 6 sets of British diagrams

- Several sets of French diagrams.

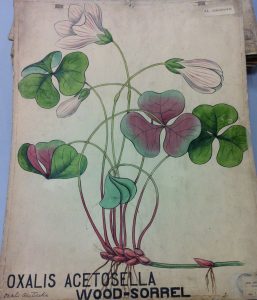

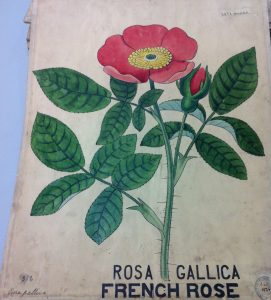

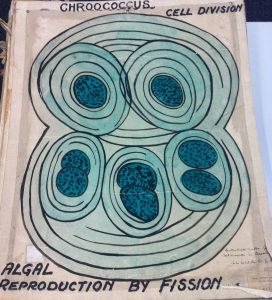

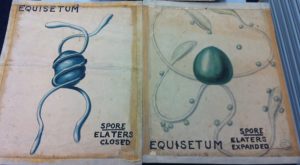

In addition, Balfour commissioned approximately 2,000 hand drawn manuscript diagrams. Wall diagrams were considered “one of the most important media for the teaching and learning at different levels of education and within different fields”(Bucchi 1998). Originally numbering c.4,000 (as known from the Catalogue of Diagrams printed and published in 1904 under the directive of Isaac Bayley Balfour), the diagrams depict flowers in various stages of growth viewed in frontal, transverse and vertical sections; flowers with dissected perianths; diagrams of greatly enlarged organs and sections through those organs; tables of temperature, humidity and rainfall; diagrams of microscopy equipment; charts classifying colour and odour and, diagrams depicting the distribution of plants across the globe and paleontological specimens. Some of the diagrams were arranged by function illustrating plant processes drawn over more than one diagram board. The majority of the remaining diagram boards measure 20 x 30cm, some consist of two boards joined with material. Two are considerably larger, consisting of twelve conjoined boards. The subject matter was typically drawn in the centre of the board with the name or title added in thick black capital letters along the bottom edge. In many cases the illustrations were drawn to be visually eye catching, coloured in bright paint and highly stylised.

On several diagrams Balfour, his writing small and unclear, has annotated the diagrams themselves; correcting inaccurate morphological aspects, rendering a structure more clear, or adding notes of clarification.

A highly coloured aesthetically appealing and scientifically accurate illustration of Oxalis acetosella. RBGE Archives

Large format wall diagrams not only made the visualisation of small objects possible when lecturing to a large group of students or to large public audiences, they also provided a medium for visually demonstrating plants which were either out of season, not grown in the garden or too delicate to bring into the classroom environment. The role of the wall diagram was fundamental to Balfour’s style of teaching.

The Dynamic Nature of Models

The 1868 Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh report that “there had latterly been added to the Museum of the Botanic Garden, two series of models, executed by R. Brendel, Breslau and M. Auzoux, Paris, illustrating the different parts of flowers, fruits &c.” (Anon 1868).

The RBGE botanical teaching models include examples by Dr Louis Thomas Jérôme Auzoux (1797-1880) of France, models by Robert Brendel (c.1821-1898) and his son Reinhold(c.1861-1927) in Breslau and Berlin and models by Heinrich Gasser, technician to the German botanist Gottlieb Haberlandt (1854-1945). Also in the RBGE archive are several wax models by an unknown maker. The models, presently numbering 66 (the original number is not known), depict whole, transverse or vertical sections through plants and, highly magnified representations of processes or individual organs. Many have removable parts facilitating access to small or obscure structures.

Although it is not known which Auzoux’s models Balfour purchased, it is known, from the Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh that he purchased a series in 1868. In 1869 the description of the botanical models given in Auzoux’s Trade Catalogue was as follows: “Preparations for the teaching of botany and vegetable physiology, with a magnification of 10 times the diameter, showing the constituent parts of the flower, the fruit, the seed, the stem, etc. Each part may be removed and detached separately, to make clear all the details and any of the modifications in the sepal, the petal, the stamen, the anther, the capillary leaf, the ovule, etc. in different stages of flowering, ripening, and germination”. This provides some evidence of where in the curriculum the models may have been used. The set was clearly a comprehensive teaching tool intended for use in lectures to demonstrate morphology, physiology, reproduction and taxonomy (all sections of Balfour’s teaching curriculum).

Although it is not known how many models Balfour had, Auzoux only produced models of 23 plant species. It is likely therefore that the Auzoux models were intended to be used in conjunction with other demonstrative objects including living and herbarium specimens and illustrations. As observable in the teaching diagrams, it is possible to infer that each model was intended to facilitate recognition of important or distinguishing features rather than be considered true representations of the botanical kingdom.

The distinguished Universities of Oxford and Cambridge did not employ the use of demonstrative material to aid in the teaching of botany as it was feared that use of such methods would benefit the “giddy sightseer instead of the learned or learning scholar” (Olszewski 2010). In a letter in the RBGE archives from Brendel to Balfour the use of models by Balfour and their use in Britain was explored. The letter detailed the shipment of 30 botanical models and Brendel’s aspirations for their British success, “You may be quite sure of obtaining highly successful botanical models which I trust by your kind recommendation will be introduced into all english high class scientific and botanical institutions”(RBGE archive (i) n.d.) It is arguable therefore, that the use of models in the University of Edinburgh Botanical Classes not only acted as a positive advert for their use but also that Balfour may have pioneered their use in Britain. Unlike Babington, Balfour was eager to teach more than systematics and willing to engage with non-academic audiences. Unlike Oxford’s Professors, The University of Edinburgh allowed the use of modern methods.

The Necessity of Teaching Through Living Specimens

“The summer session of the botany classes commenced on Tuesday morning. The first lecture was given in the classroom, Royal Botanic Gardens, at eight o’clock, and the large attendance of students testified to the great popularity of Professor Balfour. The room was beautifully decorated with plants, illustrating the forms of vegetable life in different parts of the globe. At half-past eleven the Professor delivered the first of a course of lectures to the members of the Edinburgh Ladies Educational Association” (Dundee Courier 1871 May 4).

The use of living specimens, either demonstrated in the garden or brought into the classroom, added to the library of teaching technologies employed by Balfour. The value attached to those specimens lay in their ability to illustrate species. Combining diagrammatic representations with real specimens balanced a students’ perception of illusion and reality (Secord 2002). An example from Balfour’s personal lecture notes indicates how he used such specimens, “Lecture at 6 – Linnean system. Illustration by means of fresh specimens. Rannunculus, Aquilegia, Digitalis, …Linnea, Salvia”(UEA Papers of Professor John Hutton Balfour). Further specimen use is revealed in the diaries of a student William Carmichael McIntosh, “Balfour [reported] on the various forms of plants and the usefulness of botany to the accomplished surgeon or physician, showed specimen of monkey plant, pitcher plant and ascidias in air” (McIntosh 1858). On other occasions it may be possible to determine that living specimens were used to create a lasting impression with the students.

The Botanic Garden as a Significant Site of Teaching Practice

The Botanic Garden was also used as a teaching space. The intellectual and civic importance associated with Botanic Gardens was emphasised in a speech by Balfour during his period as Professor of Botany at Glasgow University. Referring to Glasgow Botanic Garden Balfour stated: “I cannot omit the opportunity of impressing upon you the importance of a garden in the prosecution of botanical studies…..In Glasgow you possess a Botanic Garden which has occupied a distinguished place among others of a similar kind. Nothing can do more importance to the health and wellbeing of a densely populated town than having a garden worked to the formation of public gardens to which they have easy access. Nothing in my opinion can tend more to prevent the spread of epidemic disease” (Balfour n.d (i)).

Balfour’s consideration of the importance of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh can be viewed through his consistent use of the garden in his teaching of the botanical classes. At the culmination of the taught section of the 1846 summer session, Balfour reported the successful realisation of 65 lectures, 12 examinations, 12 trips and 12 demonstrations in the garden. Further details of the garden demonstrations and the use of associated buildings as part of the ‘field’ of botany came from the University Court minutes of 1859: “demonstrations (from 9 to 10am) on the Natural Orders, in the open ground of the garden; on the preparations, in the Museum of Economic Botany; and on the plants, in the Hot-houses. Saturday occupied with Excursions and demonstration in the fields” (Anon 1859)

Garden demonstrations were held every Monday, Wednesday and Friday of the summer session. William Carmichael McIntosh records his attendance in the garden at 07:00 am. McIntosh also gave details of a tour of the Botanic Garden with Balfour in which it was noted that Balfour made efforts to “point out the most important features of the place –[he] pointed to the fact that the branches of the birch close to the trunk came off at an acute angle – that the ends of the branches went the opposite way and hung down – he pointed out the arrangement of the natural orders…and the old Yew which was transplanted 3 times” (McIntosh 1859). From the description of the garden tour it would appear that Balfour taught from what he was presented with rather than from a pre-assigned curriculum.

The Class Herbarium and its Role in Lectures.

Herbarium specimens were crucial in the teaching language of botanical science. The Class Herbarium was originally accommodated in the botanical classroom and could only be consulted by students with the permission of the Professor. The collection comprised over 14,000 specimens ranging in date from 1765-1873 with the majority of specimens collected between 1821-62. The year following his retirement in 1879 Balfour presented his Class Herbarium to the Perth Literary and Antiquary Society. Now housed in what has become the Perth Museum and Art Gallery, the herbarium collection has undergone minimal modern curation and though removed from the cabinet the original order is intact.

Aristolochia sp. specimen sheet from 1769 From Perth Museum and Art Gallery

Three specimens of Betonica officinalis collected from different locations. Perth Museum and Art Gallery

The teaching herbarium may be considered under two broad categories: a taxonomic herbarium or, specimen sheets arranged according to genus and family and, as a morphological herbarium consisting of herbarium sheets arranged by specimen character and morphology.

Study of the herbarium itself together with additional detail from the textbooks and teaching technologies reveal ways through which the herbarium may have been incorporated in the teaching of botanical science. Specimen sheets of diseased plants formed one section of the morphological herbarium. One such section included a specimen of Avena sativa (Oat) infected with the fungal disease Smut. Onto this specimen sheet Balfour had inscribed, “specimens of smutted oat plants in the first stage of the disease” (original emphasis) (Perth Museum and Art Gallery). In the section of the Class Book of Botany principally addressing Disease, particular reference is made to smut in oat crops, “Another disease called Smut or Dust-brand is caused by a fungus called Uredo segetum…The fungus then consumes the whole of this fleshy mass, and at length appears between the chaff scales in the form of a black soot-like powder…..Smut is rare in wheat, it is common in Barley and more so in Oats”(Balfour 1854). During an Agriculture Course lecture to students of the University of Edinburgh, further reference was made to Smut in Oat crops. In a note intended for his personal use, Balfour detailed the methods through which he intended to demonstrate the effects of smut, “[by] specimens in museum at garden and models” (Balfour 1857). This excerpt from Balfour’s lecture notes reveals an approached geared to object use in order to demonstrate specific detail.

The taxonomic section of the Class Herbarium appears to have been specifically compiled from specimens from many sources. Several specimen sheets are from the Botanical Society of Edinburgh, such sheets show the Society label and, the carefully mounted specimens indicate detail of location of collection, by whom and the species name. Other specimen sheets demonstrate scant detail of collector or location. In some cases, it is possible to detect the removal of the specimen from the original sheet and the subsequent reattachment to another:- no reason for this is given. Further specimen sheets indicate a focus on morphology where several specimens of the same species but from different geographic locations are all mounted on one sheet. The morphological section of the Class Herbarium appears to have been arranged with a focus on shape and structure; little consideration appears to have been given to collector, location, or species.

Although we know from the University Calendar that the Class Herbarium was accommodated in a cabinet in the botanical classroom, one specimen sheet with a material tag, similar to those on the teaching diagrams indicates that some specimen sheets may have been hung. Specimen sheets were not large and were relatively fragile therefore, the pedagogic benefit of this is unclear. Where the class diagrams were large, bright and easily seen from around the classroom and the models robust against handling, the herbarium specimens were comparatively small and delicate. Therefore the role of such specimens as a demonstrative object to approximately 300 students is unclear.

For more information please refer to the references below

Anon 1859. University Court Minutes. University of Edinburgh Archives. EUA IN1/GOV/CRT/Da.23

Anon 1868. Miscellaneous Notices. Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh . IX. 304.

Balfour, J.H.B. (1854) The Class Book of Botany; Being An Introduction to the Study of the Vegetable Kingdom. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black.

Balfour, J.H.B (1857) Agriculture Course of Botany. Unpublished. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh JHB2/1/14.

Balfour, J.H. (1873) Guide to the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas.

Balfour, I. B. (1913) A sketch of the Professors of Botany in Edinburgh from 1670 until 1887. In: Oliver, F.W. (ed) (1913) Makers of British Botany: a collection of biographies by living botanists. London: Cambridge of University Press. 280-302.

Balfour, (n.d) (i) Popular Lecture on Botany, Glasgow. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Archive. JHB2/2/1.

Bucchi, M. (1998) Images of Science in the Classroom: Wallcharts and Science Education 1850-1920. The British Journal for the History of Science. 31 (2) 161-184.

Evertsson, J. (2014) Classroom wall charts and Biblical history: a study of educational technology in elementary schools in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Sweden. Paedagogica Historica: International Journal of the History of Education 50 (5) 668-684.

Letter from R. Brendel to J.H. Balfour (1866). Archive of Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. (JHB1/3/377).

McIntosh, W.C. (1859) Edinburgh University Classes in Botany 1859. St Andrews University Special Collections (ms37106 /13)

Olszewski, M. M. (2011) Dr. Auzoux’s botanical teaching models and medical education at the universities of Glasgow and Aberdeen. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 42, 285-296.

Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (1904) Catalogue of Diagrams 1904. Glasgow: His Majesty’s Stationary Office.

RBGE Archive (i) Letter from Brendel to Balfour n.d. JHB/1/3/377

Secord, A. (2002) Knowledge on a Plate: Pleasure and the power of Pictures in promoting early nineteenth century Scientific Knowledge. Isis. 93 (1) 28-57.

The Dundee Courier. (1871) The Botanical Classes in Edinburgh University. May 4th.

UEA (University of Edinburgh Archive) Papers of Professor John Hutton Balfour (MS 2738)

Julia

Dear Ms. Stoddart,

my name is Julia Echner, I´m a conservator student from Germany, currently writing my master thesis about a collection of botanical plant models by Robert Brendel at the University of Jena in Germany.

I found this article while searching for other institutions with such collections. You mention in your article that there are Brendel models in the RGBE. I have to say I´m not very familiar with the Gardens being from Germany. Are the models on display in a kind of museum at the RGBE or in storage? Are they sometimes still used today?

Also, do you know if there was any conservation treatment done to the models and could you give me some information about it?

Lastly, I was wondering if it might be possible for you to give me access to the mentioned reference letters of Brendel to Balfour.

Thank you very much for your effort in advance, any information is welcome.

Kind regards, Julia Echner

Lorna Mitchell

Hello,

We have 81 botanical models in our collection, the majority of which were produced by Brendel; we have a spread-sheet that lists our collection and I would be very happy to send that to you if it was of interest. Some of the models are displayed in a wood / glass cabinet in the RBGE Library while others, primarily those which are particularly fragile and / or damaged, are stored in the Archives. A small number are still used in teaching classes today.

Other than surface cleaning no conservation work has been carried out on the models but this is something that we would like to do at some point in the future. If you can offer any advice regarding their conservation based on your research for your thesis this would be very much appreciated.

I can provide you with a scanned copy of the letter from Brendel to Hutton Balfour.

Please accept my apology for the late response to your comment and I hope that it is still useful.

Yours sincerely,

Lorna Mitchell

Head of Library, Archives & Publications

Cristiana Vieira

Hello!

I am the curator at Porto Herbarium and besides some Brendel models I suppose I also have two models by H. Gasser, which by the information you collected corresponds to Heinrich Gasser, technician to the German botanist Gottlieb Haberlandt .

That is very interesting and I wonder if you have any more information on the history of making of H Gasser models and periods of selling. I have a Sellaginella and a Lycopodium model I need to catalogue.

Thank you very much in advance for any help and congrats on the information displayed on this page.

Looking forward to hearing from you.

Best regards!

Cristiana Vieira

Dear Ms. Stoddart,

my name is Cristiana Vieira, curating Porto HErbarium at MHNC-UP.

I was wondering if you have any more information on Heinrich Gasser?

I have some models of ferns at the Herbarium I would love to catalogue with greater information.

Thank you very much for your effort in advance, any information is welcome.

Kind regards, Cristiana