The Yucca elata was donated to RBGE as seed from Michigan University Botanic Garden in 1995 and was subsequently planted in the newly landscaped Arid Lands House in 1999. After 21 years it has come of age and has produced a flower spike!

Ian Ross (& Brian from SG Access) removing the glass

Native to the grasslands of the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts, Yucca elata, commonly known as the soap tree, can grow to 5m and produces flower spikes over 2m tall. It is this flower spike that is causing us a few problems as it was pressing against the glasshouse roof.

In the hope that we can get it to finish flowering a pane of glass has been removed to allow the spike to keep growing

The Yucca elata has a number of alternative ethnobotanical uses:

- Native Americans used the fibre of the leaves to weave baskets to collect the edible buds, petals and fruit of the plant.

- The roots and trunk contain saponins, commonly used as a substitute for soap.

- In drought conditions, ranchers use the plant as an emergency food supply for their cattle.

The main fact I discovered about Yucca elata is the co-dependant relationship that has been in existence for millions of years between the plant and a little white moth – Tegeticula yuccasella. This relationship is incredibly important as neither the Yucca or the moth can survive without the other. The moth’s larvae depend on the seeds of the Yucca plant for food, and the Yucca plant can only be pollinated by the Yucca moth – a fascinating example of coevolution and mutualism.

Each spring, adult moths emerge from underground cocoons and the males and females meet up with each other on a Yucca plant to mate. When the female is ready to lay eggs she first goes to a flower to collect pollen.

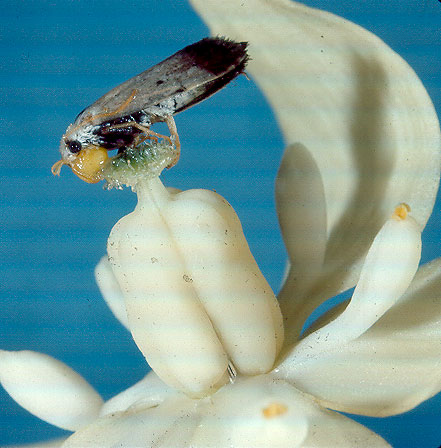

A Tegeticula moth is depositing a pollen ball onto a stigma of a Yucca plant. ©Sherwin Carlquist, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Yucca moths do not have a long nectar sipping tongues like most moths; instead, they have two short tentacles near their mouth which they use to scrape pollen from the anthers of the flower. As she collects the sticky pollen, the female Yucca moth rolls it into a ball and sticks it under her ‘chin’ before flying to another flower.

When she arrives at the second Yucca flower, usually one that has very recently opened, she goes straight to the bottom to find the ovary. She creates a small hole in the ovary and lays her eggs inside and then makes her way to the stigma and carefully packs her pollen ball into tiny depressions within the style, thus pollinating the plant.

She then marks her territory with a pheromone, this scent marker alerts other moths that eggs are already present and they are less likely to lay more eggs in the same place. When the moth eggs hatch, the larvae feed on some (but not all) of the developing seeds and once fully developed they chew a hole in the wall of the seed pod and drop to the ground. The larvae then burrow into the ground to pupate over winter to emerge in spring as adults and begin the cycle all over again.