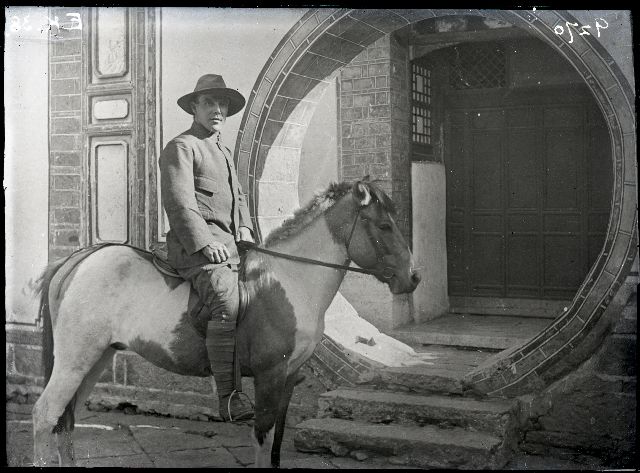

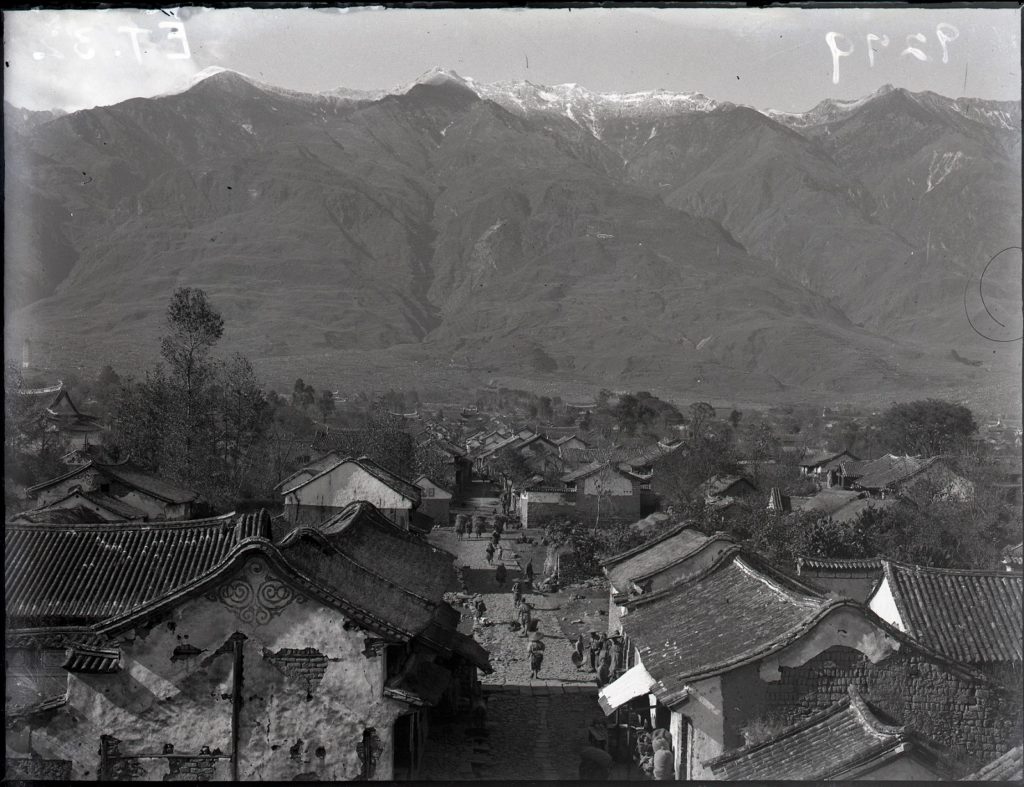

I am fortunate to be able to work with archive material produced by people like plant collector George Forrest (1873-1932), who travelled extensively in Yunnan province, southwest China between 1904 and 1932. He tells of his experiences as he travels through the country, and I hope to be able to share some of his stories from his letters, in particular those he hears and recounts from the indigenous people of Yunnan whom he travelled amongst. This one is the legend of the Goddess of Mercy – he presumably heard it from members of the Bai ethnic minority group when he first spent time in and around the ancient town of Dali, situated between the banks of the Er hai (洱海) lake to the east and the Cang Shan (苍山) mountain range to the west. This excerpt can be found in a letter he wrote to his fiancée Clementina Traill on the 24th March 1905.

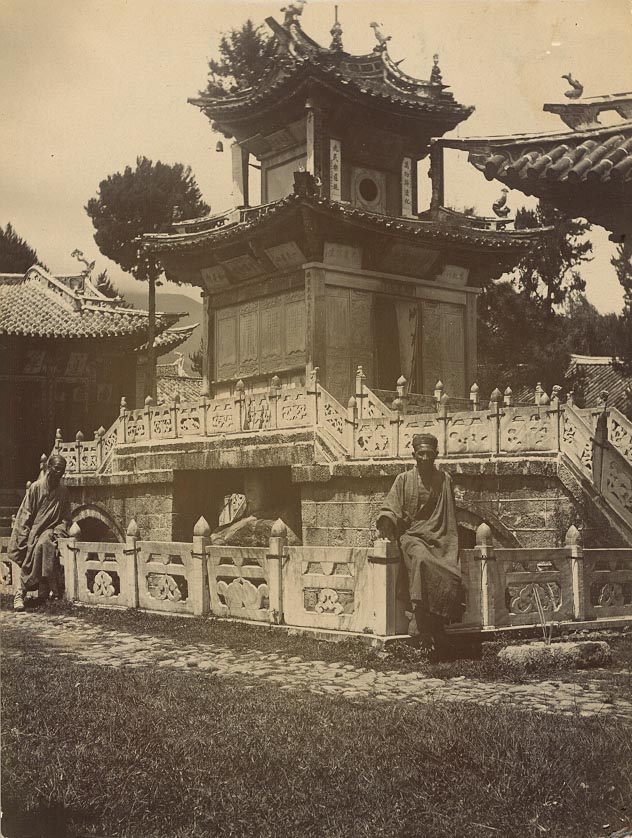

On the road to Tali [ancient Dali], about 20 li [just over 6 miles] from Hsia Kuan and 10 from the city, is situated the Kuan Yin Tang [Guanyintang] or Temple of the Goddess of Mercy. The shrine in which the Goddess is placed is in a small house, with glass windows, built on a rock in the centre of a large pond. This is fed by one of the mountain streams and contains a good number of golden carp. A little bridge leads over to it and on the whole it has a very striking appearance. Regarding this Goddess of Mercy I give the following.

The traveller who has passed through the rich fields and flourishing villages of the Tali plain and has enjoyed the double view of hill and lake is no doubt interested to learn how this happy valley first came into existence. It appears that in the ancient days the waters of the lake lapped the foot of the Tsan Shan [Cangshan (mountain)] and there was no plain. The caverns in the hills were inhabited by a ‘Yao Kwei’ or monstrous being, who used to sally forth, and for his food tear out and devour the eyes of the Chinese in the neighbourhood.

Kuan Yin [Guan Yin], the Goddess of Mercy, pitying the sorrows of the black haired people, appeared upon the scene disguised as a venerable Buddhist nun, in her ‘Ka sha’ or yellow robe, and accompanied by a lame dog. Addressing the monster, she promised to supply him with the food he liked on condition that he would give her a patch of dry land under the hills. “How much dry land” asked the monster. “The breadth” replied the Goddess, “of my yellow robe, and the length of three leaps of my lame dog.” After some haggling a contract in these terms was reduced to writing.

But when the aged nun spread out the robe it covered a space of 15 li, and such was the uncommon agility of the lame dog, that in three leaps he covered a space of 100 li. For his food, the Goddess captured shellfish and gave the eye-like contents to the ‘Yao Kwei’; the voracious, but unwary monster seems to have thought that he had been swindled and became obstreperous, whereupon the Goddess seized him and interred him in a hole or cavern in the earth near Hsi Chou, where there was only a small open slit through which he could breathe. In his struggles his fiery breath issuing from this aperture burned up the waters of the lake. But the Goddess had cast a spell on the monster; so long as Chinese assemble at the West Gate of Tali [Dali] during the third moon, so long must the monster remain in ‘durance vile; wherefore to this day at the commencement of the great spring fair, the General comes out in state and fires off all his artillery, so that the dragon may know that the time of his release is not yet come.

In case this narrative fails to convince you, I may point out that the length of the Tali plain from the upper to the lower pass is in fact 100 li, and its breadth is 15 li. Also, is not the shore of the lake littered with empty shells, the contents of which have been devoured by the ‘Yao Kwei’. Is not there at Hsi Chou a long narrow strip of land stretching into the lake from which the water was blown by the struggling monster? Was not the contract between him and the Goddess reduced to writing and engraved on stone, that all might see?

And finally, is it not a fact, that, to this day, an annual crowd has assembled outside the West Gate for the third moon fair, and that the ‘Yao Kwei’ has never once emerged from his prison.

George Forrest to Clementina Traill, 24th March 1905 (GB235 FRG/1/1/2/5, pp5-8), RBGE Archives

This is the dragon which I was supposed to be going to Tali to release, and as a reward I was to get all the gold and jewels which were in the lake…