It may only take a mammal 12 seconds to poop – but poo contains a treasure trove of information about the animal and its environment that can take years to unravel

All animals have to do it and according to recent work it doesn’t matter if you are a giant panda, dog, mouse or elephant – it takes about 12 seconds poop. While not the most pleasant sample to work with, there is a lot of information hidden in ‘poo DNA’. We can find out about the individual that produced it, the organisms (good and bad) in its gut and the plants and other animals in the environmental that it has eaten.

Every living thing contains DNA and leaves traces of that DNA in the environment. Poo DNA is a treasure trove of information that can be used to understand species, ecosystems and food-webs.

The animal that deposited the poo has left traces of its DNA. This allows us in determine which species of animal the poo came from, without needing to see the animal. We can even work out exactly which individual it was! This means we can track individual animals, or monitor the size of a population without disturbing them, just by collecting their poo. We can also find out about the health of the animal by the communities of organisms that live in animal’s gut, which can be beneficial, aiding in digestion, or parasitic / infectious just by sequencing the DNA found in poo.

BUT poo DNA also contains information on the diet of the animal – the plants and animals that have been eaten. This can tell us about the other species in the area and the food-webs within the system. For example understanding the different species of plants that an animal feeds on is critical to ensuring their habitat is effectively conserved, especially if they have highly specialized diets, such as giant pandas.

How it works

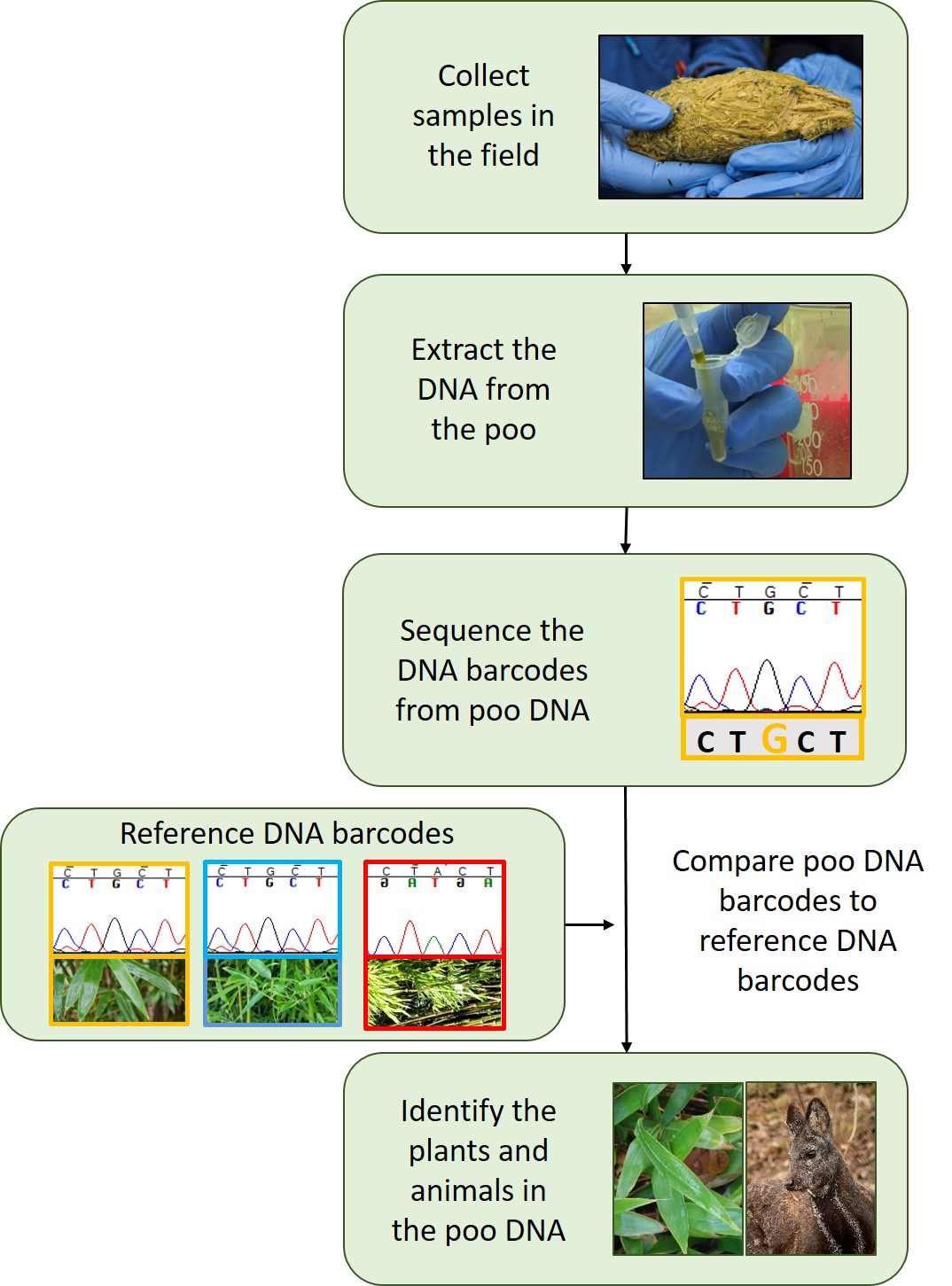

Once a sample is collected from the field the DNA is extracted. This is a mixture of DNA from all the different animals, plants and microorganisms that were in the poo sample.

To identify the individual species, we look at specific bits of the DNA that are good at telling species apart. These are known as DNA barcodes. Once we have sequenced these DNA barcodes we compare them to a reference set of DNA barcodes. Reference DNA barcodes come from sequencing the DNA of known plants and animals that are usually held within herbaria and museums and have been identified by experts (taxonomists). The specimens within herbaria and museum are critical to making sure that we accurately identify which species are in poo DNA. It also means that we can go back later and do this for another animal in the same or different location and compare the results. Without this it would be almost impossible to track how an animal’s diet changes throughout the year, or understand the differences between locations.

When a DNA barcode from the poo DNA matches one in the reference DNA barcodes we know that the DNA of that species was in the poo sample and was probably eaten by the animal that deposited the poo. This tells us that not only is that species in the area, but that it is a potentially important food source for the animal we are studying.

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh is using this technology to investigate the diet of giant pandas. Sound simple? Well it actually might be more complex than you think. Check out our Botanics Story on Using DNA to understand giant panda diet.