Following some hair-raising adventures, James Bruce of Kinnaird (1730-1794) was the first white Anglo-Saxon Protestant to reach the fountains of the Blue Nile in Ethiopia. He discounted the claims of a Spanish Jesuit who beat him by 157 years and in November 1770, he raised a coconut cup of Nile water to the health of his monarch King George III. But Bruce is interesting for many other reasons: the scandal caused by his five-volume account of the expedition, rubbished by Samuel Johnson (who disbelieved the story of rump steaks cut from ambulant cattle) but subsequently shown to be substantially accurate; his appearance (all six foot four of him) in the notorious Zoffany conversation piece showing male connoisseurs ogling sculptures and paintings of female flesh in the Tribune of the Uffizi; his links with the Carron ironworks and the early industrialization of Scotland; the cast iron obelisk in Larbert churchyard that he commissioned in 1785 to commemorate his second wife Mary (she died at 31, failed by her physician John Hope) which, nine years later, also served as his own memorial; the botanical drawings made on the African expedition by the Bolognese artist Luigi Balugani; and, last but not least, the fact that in the 1770s some of his Abyssinian plants were cultivated in the Edinburgh Botanic Garden.

Two artefacts have brought Bruce back to mind in recent days. The first in an exhibition at Bonham’s in Edinburgh of some treasures from Broomhall, the Fife mansion of the Earls of Elgin, by whom Bruce’s collections were inherited. Balugani’s drawings, having survived a period of abandonment in the Nubian desert, have long since crossed the Pond, but a brilliant tartan surcoat and waistcoat that belonged to Bruce formed part of the exhibition. The second reminder is in the form of a drawing of one of Bruce’s houses. In Edinburgh several years ago I bought a pair of large, but somewhat tired, watercolours by the York artist Henry Cave (1779-1836), which each includes a significant Highland-Perthshire house, Dalguise and Ardchullarie, and it is their successful recent conservation by Helen Creasy that has prompted this blog.

Reproduced with the kind permission of the Broomhall Home Farm Partnership. Photo Gilberto Martinez.

Ardchullarie

Although Bruce died in 1794 (after falling down the steps of his house at Kinnaird, near Larbert in Stirlingshire) his memory lived on. On the back of his painting Cave wrote ‘View betwixt Loch Earn & Callander, on the right Bruce’s House – the Abyssinian [traveller], Loch Lubnaig on the left’. The date of Cave’s Scottish tour is unknown, but is likely to have been around the same time as that of a more famous, brother-sister, pair of travellers in pursuit of the sublime. On 10 September 1803 Dorothy Wordsworth wrote in her diary:

A neat white dwelling on the side of the hill over against the bold steep of which I have spoken, had been the residence of the famous traveller Bruce, who, all his travels ended, had arranged the history of them in that solitude as deep as any Abyssinian one among the mountains of his native country, where he passed several years … The house stands sweetly, surrounded by coppice-woods and green fields.

For the historically minded botanist this corner of the Highlands has an additional significance. On their way to Callander, the Wordsworths and Cave must have passed another mansion, Leny House, and it was here, 20 years after Bruce’s death, that Francis Buchanan-Hamilton retired to his own ancestral home. In India his had also been a life both of adventure and scholarship, and it is one of those odd historical coincidences that, after spending time in Nepal and surveying the Bengal plains at the foot of the Himalaya, he too should settle down to write up some of his own life’s work in the shadow of the same ice-scoured hills as the Abyssinian traveller.

Leith Walk

Bruce was generous with the seeds that he brought ‘out of Africa’. They were known to have been grown in the botanic gardens of Kew, Paris and Florence (perhaps also Vienna), as related in a beautiful book by Hulton, Hepper and Friis. This forms a catalogue of Balugani’s botanical drawings now in the Yale Center for British Art, having been purchased by Paul Mellon from the Earl of Elgin in the 1960s and ’70s, but it also provides a summary of Bruce’s life and travels and a taxonomic treatment of the botanical collections. Despite the fact that among the collection is a monochrome drawing of Eragrostis tef made in the Edinburgh garden by John Hope’s assistant Andrew Fyfe in 1775, the authors did not pursue this; had they done so they would have discovered that in his Leith Walk garden Hope grew at least five other species supplied by Bruce who was given a gold medal by way of reward. Details are to be found in a notebook dated 1779 in the National Records of Scotland (GD 253/144/14/1 (2)). In this book are listed the names of some of the most important of the exotic plants that Hope annually demonstrated to his students in the second part of his summer lecture course. These include ‘the moving plant of Bengal’ (which he called ‘Hedysarum gyrans’), the varnish tree, the tallow tree and tea from China, Buddleia globosa from Chile and five of ‘Mr Bruce’s’ plants (though, oddly, not including the tef). For three of these plants Hope recorded the local name, which must have been supplied by Bruce, and for three an ethnobotanical use.

Although Hepper & Friis realised that the best-known of Bruce’s plants (Brucea antidysenterica, which cured the traveller of dysentery) had been described in London, they seem to have been unaware that at least four other species must also have been described from plants grown at Kew by Sir Joseph Banks’s librarian, South-Sea travelling companion and Linnaean pupil, Daniel Solander. For some reason Solander did not publish the names, but Hope clearly had access to them and used them (give or take the odd phonetic spelling) at Leith Walk.

Here are the six Bruce plants grown in Edinburgh in the 1770s under their currently accepted name, along with the unpublished the Solander name and their Amharic name and use [with additional information from Hepper & Friis]:

- Brucea antidysenterica J. Miller (‘Brussia antidysenterica Sol.’, wooginous, [against dysentery]).

- Phytolacca dodecandra L’Héritier (‘Phytollaca Brussis Sol.’, endowd, as a soap).

- Rumex abyssinicus Jacquin (‘Rumex hastata Sol.’, mokoko, to preserve butter (curiously, as was its cousin Rumex alpinus in Scotland)).

- Solanum adoense A. Richard (‘Solanum farinosum Sol.’, [merjombey], for tanning hides).

- Rhamnus prionoides L’Héritier (‘Rhamnus mysticanus Sol.’, [gesh, for fermenting mead])

- Eragrostis tef (Zuccagini) Trotter [‘Poa abyssinica’, tef, cereal].

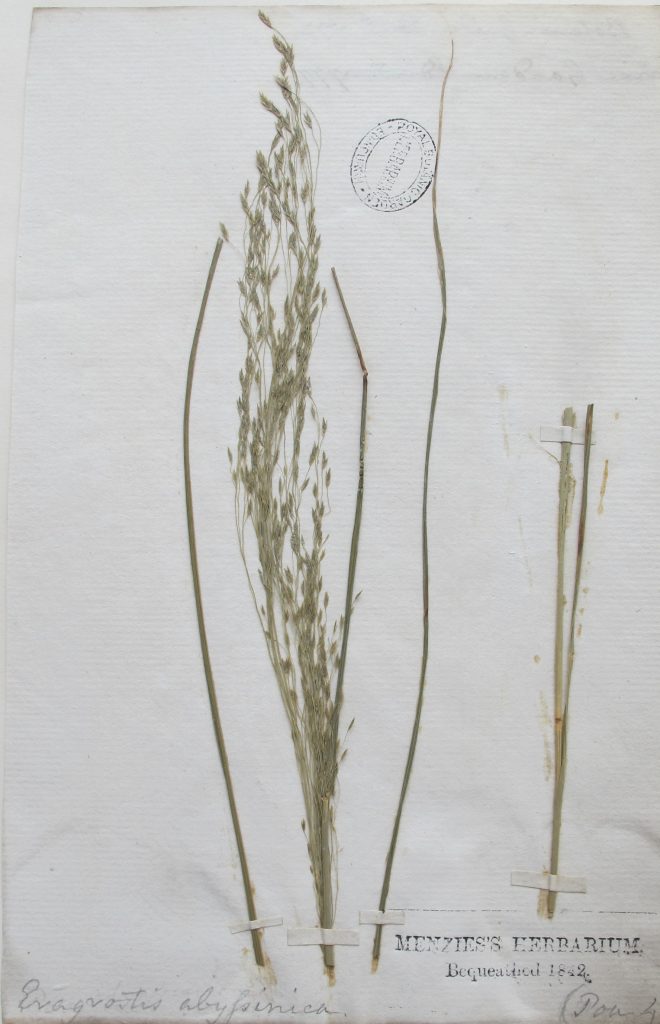

Living plants in gardens come and go, and none of these remains in cultivation at Edinburgh today. Paradoxically it is the Hortus Siccus that long outlives the Hortus Humidus, so the only tangible memorial of Bruce’s plants is a herbarium specimen of tef, collected in the Leith Walk Garden in 1777 by another great traveller, Archibald Menzies.

References

Hulton, P., Hepper, F.N. & Friis, I. (1991). Luigi Balugani’s Drawings of African Plants. New Haven & Rotterdam: Yale Center for British Art & A.A. Balkema.

Knight, W. (ed) (1897). Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth 2: 102. London: Macmillan.