“Indirectly the war has robbed the Botanical Society of a member of its Council and a frequent contributor to its meetings in the person of Dr. R.C. Davie, Captain and Senior Chemist in the 4th Water Tank Company, R.A.M.C.”

F.O. Bower, Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh, v27, 1919, p342

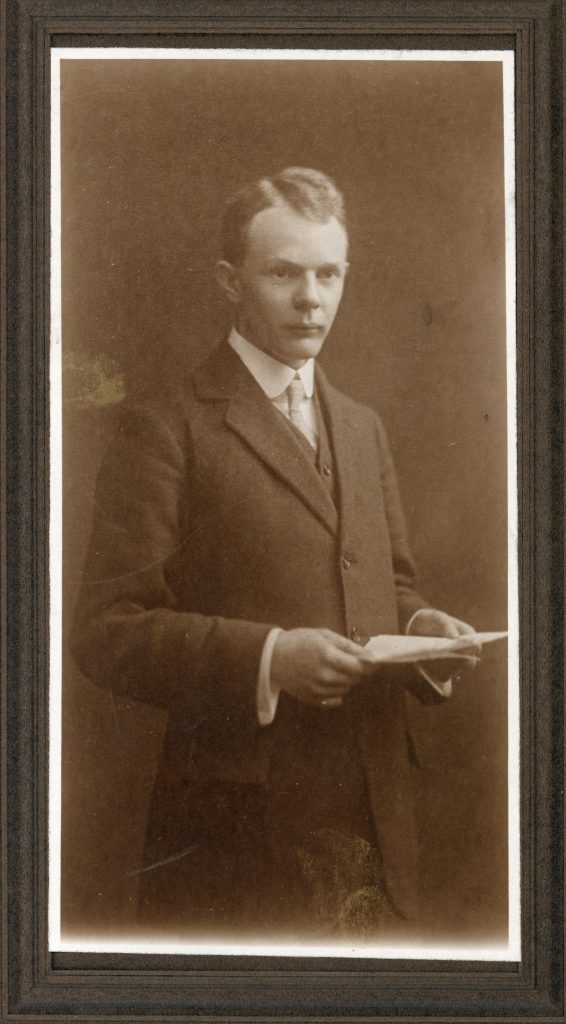

Robert Chapman Davie was born in Lisbon in October 1886, but moved to Glasgow and was schooled there at the Glasgow High School, before going to the University of Glasgow in 1904, where he graduated with a first class honours M.A. in English. This degree included some scientific courses, including one on Elementary Botany taken in 1905, and Davie found himself drawn more to that subject than English, so went on to pursue this by enrolling for another degree, a BSc. in Botany, Chemistry, Zoology and Geology, graduating in 1909 after winning the Dobbie-Smith gold medal for Botany along the way. He stayed at the University of Glasgow, becoming an assistant in the Botany Department before moving to the University of Edinburgh in 1912 to become a Botany lecturer under RBGE Regius Keeper and Professor of Botany, Isaac Bayley Balfour. Davie was given special charge of the large Teachers in Training classes and lectured on hepatics (liverworts) and mosses to Edinburgh University Botany students at the Garden. He carried on with his own studies throughout his teaching career, and soon had enough material to research a doctoral thesis on the subject of pinna-trace in ferns, and he completed this at the University of Glasgow, graduating with a DSc in April 1915 whilst still teaching and working at Edinburgh.

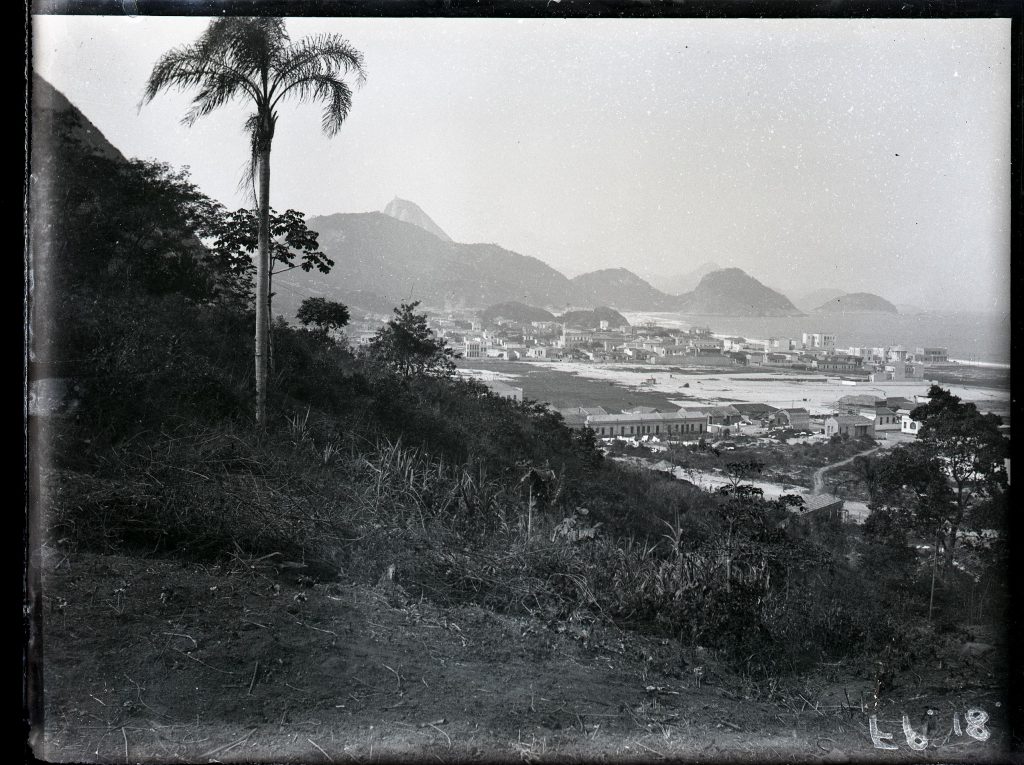

Davie’s research was interrupted in 1914, not by the war at first, but when he obtained a grant from the Royal Society to travel to Brazil to research comparisons between flowering plants. He was still working on the material he collected there when the call to join the military service finally came in 1917.

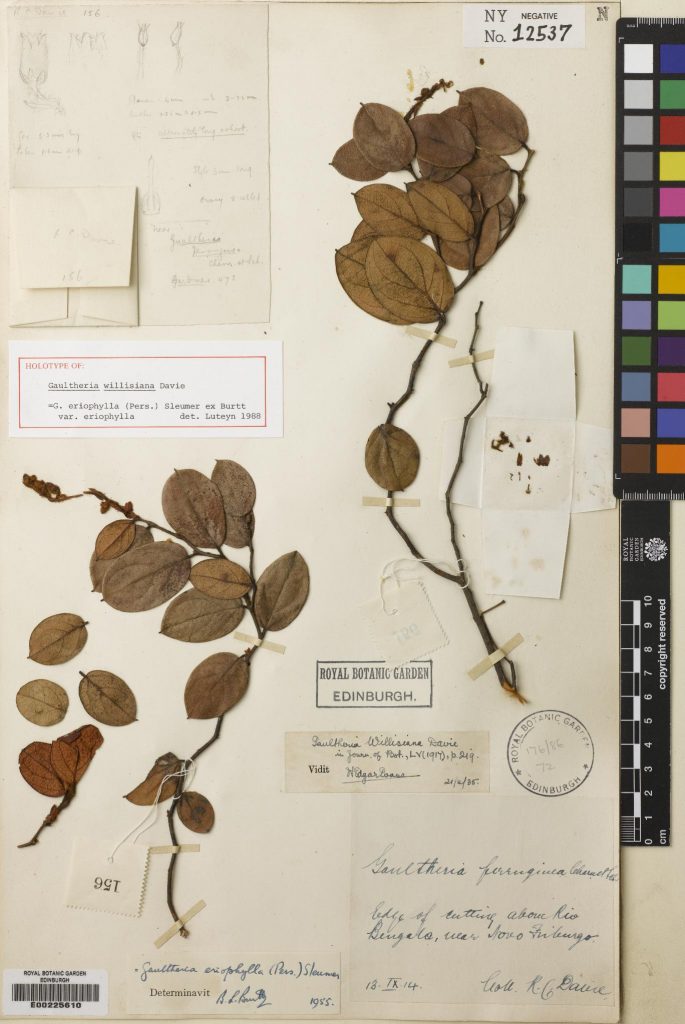

this RBGE Herbarium specimen appears to have Davie’s notes and sketches on it.

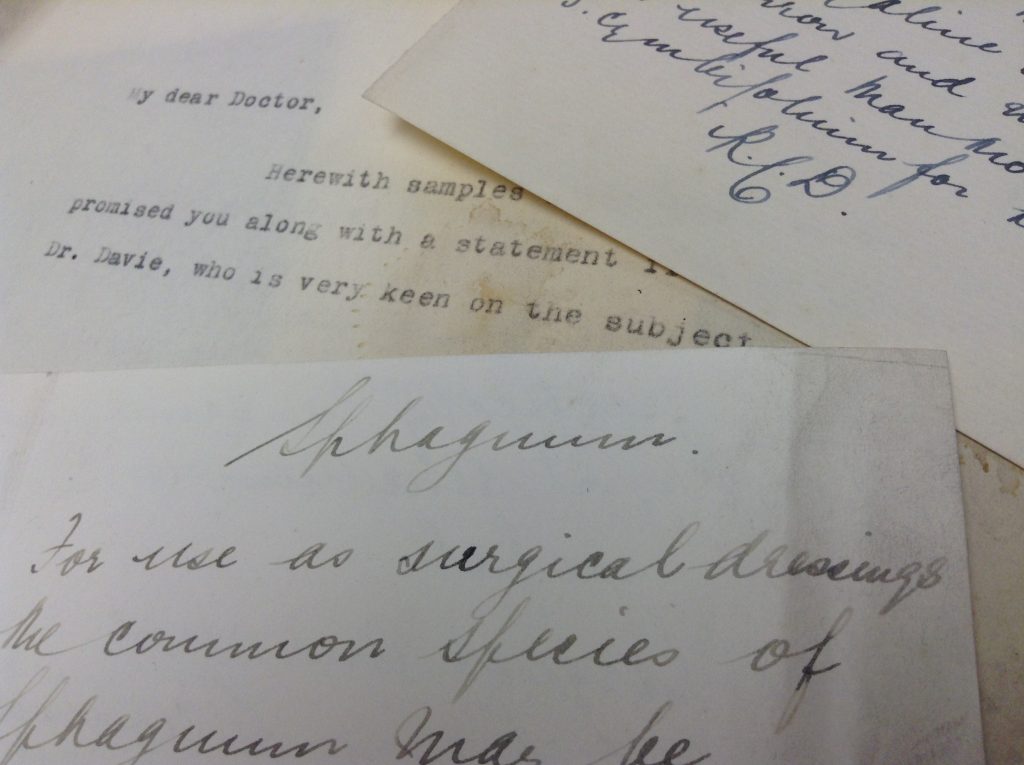

Due to effects of ill health when he was younger, it was known that Davie would not have been fit for a role in a combative branch in the army, and this may be why he wasn’t called upon to enter service until 1917, despite him apparently offering his services when war broke out. Another reason may be that his specialism in mosses meant that he was heavily involved in the work RBGE was doing in offering specialist advice to those engaged in collecting sphagnum moss to aid the war effort – the moss was used as an alternative to cotton in making would dressings, it being highly absorbent and antiseptic too. Finally though, in 1917 he was enlisted to the Royal Army Medical Corps, to a role which took full advantage of his scientific training – a Lieutenant, later promoted to Captain, and Senior Chemist in the 4th Water Tank Company, providing clean and sterile water to the troops on the Front Line, a vital and often forgotten service. He was in France with his unit during the German’s Spring Offensive, and the subsequent Allied advance in the last months of the war.

mentions of Davie being ‘very keen’ on the subject, his notes and initials.

After the Armistice, in January 1919, Davie was granted some leave to return home to Largs to visit his wife and infant daughter who was born in 1917, and it was whilst he was there he succumbed to influenza, (possibly the Spanish Flu?) which turned to pneumonia with fatal effect; he died at home on the 4th February 1919 at the age of 32.

The over-riding impression one gets of Robert Chapman Davie is one of great potential never fully realised, and one wonders what he would have achieved had he survived the illness that took him. In conclusion, here are the final words from his obituary written by Frederick Orpen Bower of Glasgow University:

Davie had already made his mark as a teacher, an investigator, and an organiser in Botany. An easy diction, with unusual command of his native tongue, gave him a good footing as a Lecturer … and an early promotion to Professorial rank was anticipated for him. A quickness of apprehension of facts and comparisons, good powers of observation, a lively imagination and a very retentive memory gave him a hold as an investigator, which a judgement ripening with age would have strengthened and directed into useful channels. As an organiser, his departmental work was marked by a cheerful efficiency. His stimulating influence was shown in the part he took in founding the Glasgow University Botanical Society. In a wider sphere his activity as one of the Secretaries of the Botanical Section of the British Association had already brought him in the relation with the great body of British Botanists. At the age of 32 he had fully qualified for years of active usefulness. It is this which makes his early death all the more lamentable. Time and opportunity were against him. So that at the moment of his death he was of the Front rather than actually at the Front, both in Science and in War.

F.O. BOWER, TRANSACTIONS OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH, V27, 1919, P344

Details and images of some of Davie’s Brazilian and Scottish herbarium specimens can be found on the online RBGE Herbarium Catalogue.

This post was written using Davie’s obituaries and biographies published in the Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh,

the Glasgow Herald and by the University of Glasgow.

Ally

Interesting article about an exceptional man. Sad to see such promise lost at an early age. His obituary, so well written by FO Bower, brings to life his fine character a century on. So graciously articulate the people of The Great War era were.

Leonie Paterson

Thanks Ally, I felt it was important to mark Davie’s life, especially as he isn’t on our War Memorial, either because he died after the Armistice, or because he was on the University of Edinburgh side of the Garden’s work – I think he may well be on the University’s memorial…

Fiona Wilding

Thank you for posting this article about my great-uncle. It has filledin some details I did not know regarding his career, as I mainly know about his private life.

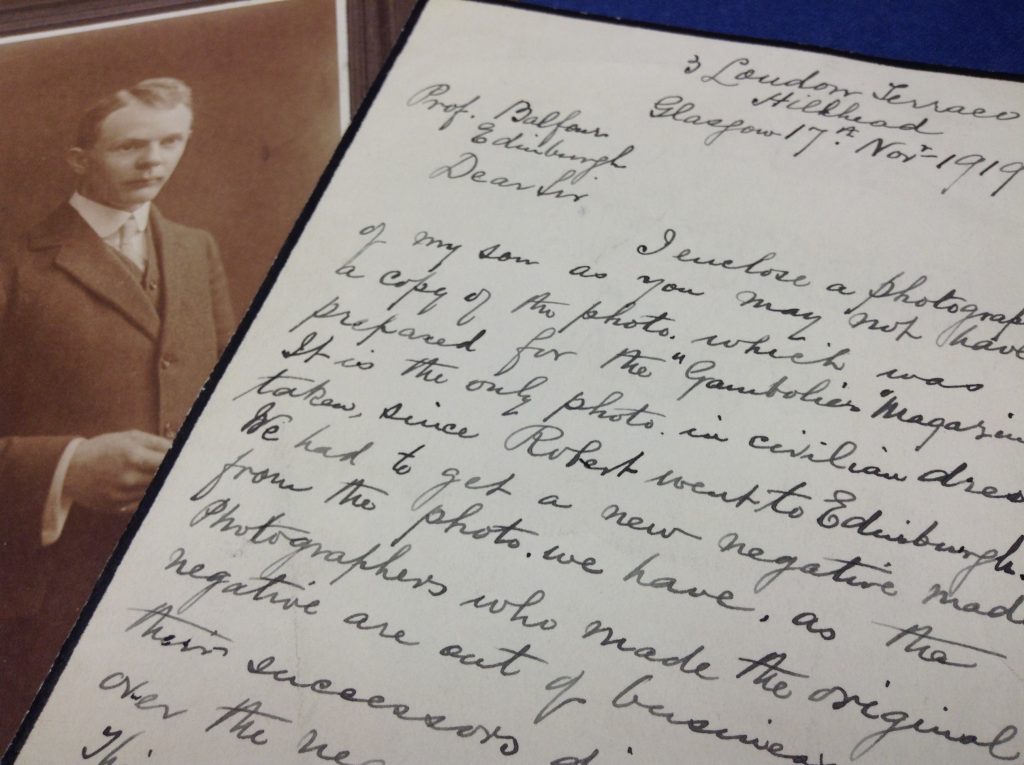

It is also interesting to read my great-grandfather’s letter.

Robert Wright

Hello Fiona. We met as children. Don’t know it you will ever revisit this page though. Robert Davie was my namesake, the infant daughter, my mother.

Kirsty Wright-Tousignant

Robert Davie was the grandfather of four children , including me and my brother Robert. My grandmother Davie followed my parents to Canada in the 1950’s ( my mother was a war bride ) . My grandmother told our mother , and us, very little about this very distinguished and apparently very loveable man . My mother was always fascinated by any little scraps of information about him , gathered during occasional visits to the UK — being told that he had a wonderful sense of humour and made people laugh delighted her. She knew about and was proud of his academic distinction. My grandmother kept a sauce-sized gold medal on a stand in her bedroom ; it was likely the medal referred to above. I have family papers which include his M.A. thesis and a holograph letter to my grandmother written on Christmas Eve , meditative and poignant. I write this as testimony to the wasted deaths of so many young men , and in mourning for what their countries, colleagues, friends and families lost. Like so many, my grandfather was not confident he would survive the war ; he had weak lungs. It is a very bitter irony that having survived the war he died in the cull of the Spanish Flu , infected on a leave granted to visit his wife and child. From what we know about him , he would probably have enjoyed knowing his family . I wore his academic gown at my graduation .

Leonie Paterson

Kirsty – thank you so much for sharing this – i know I found Robert’s story particularly poignant when i was researching it – I’m glad you were able to find it.