“Hey Zoë, we’ve found a Pinguicula!”

“I doubt it, they don’t grow in Belize.”

“Well, this is definitely a Pinguicula.”

With that conversation shouted across a hillside, we knew that some MSc students had found an exciting new plant for Belize. Not just a new species but a new genus for the country.

This is the most exciting part of running a tropical botany field course. Teaching students how to identify tropical plants and collect high quality herbarium specimens is really rewarding. But then watching them go out to discover new plants and make specimens that will become significant for the natural history of that country and conservation of plant diversity around the world feels amazing.

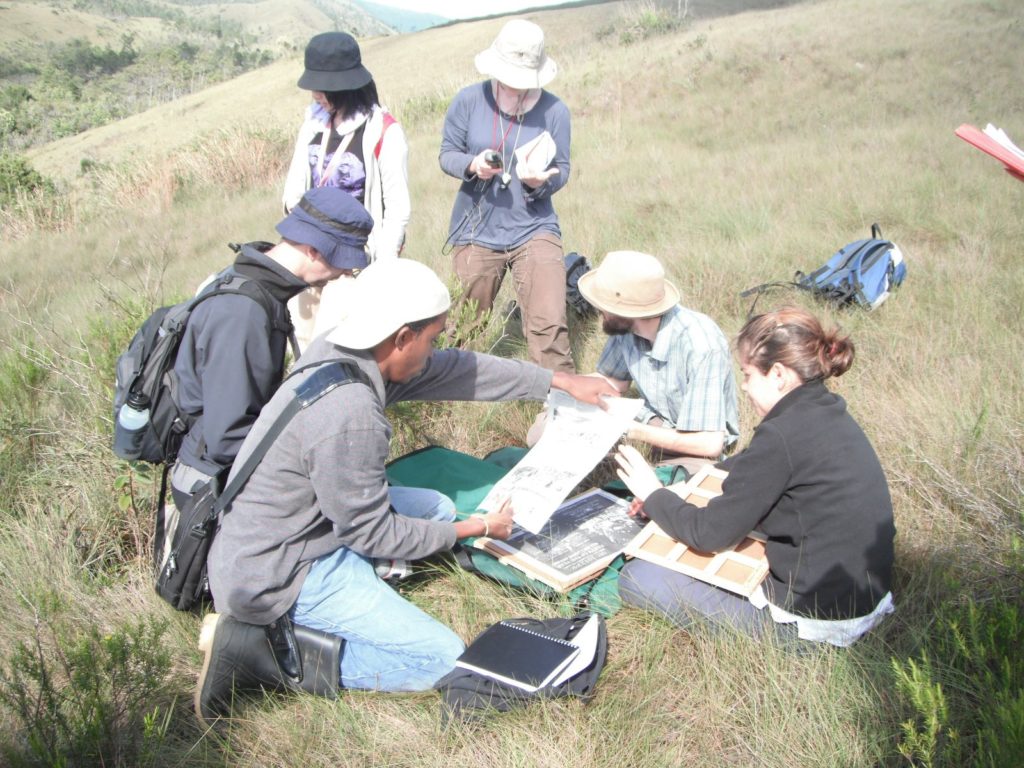

Making a herbarium specimen of a plant in the tropics can be tricky: You need to take detailed notes and photographs, then a sample of leaf for drying in silica gel, finally decisions need to be made on how to press the specimen; where to cut the branches and how to lay out the branches so that the necessary characters of fruits, flowers and leaves will be seen. While you do this you are crouching down, sweat dripping down your forehead and mosquitos buzzing around your face.

For 16 years, students on RBGE’s MSc in Biodiversity and Taxonomy of Plants field course learnt these skills in the forests and savannas of Belize. Copies of their specimens were placed in the national herbarium of Belize, the herbarium at RBGE and other international collections around the world.

This is really important because generations of students have been able to contribute to our knowledge of the flora of Belize. In a new paper we found that between 2001 and 2017, students on the field course collected over 1,700 specimens representing more than 600 different species. Another 700 specimens were collected by students who did additional fieldwork in Belize for their MSc thesis projects, bringing the total number of known species collected up to 850. (We actually think that this is an underestimate because , for some groups in which we do not have specialists, we cannot identify all the specimens to species level.)

Currently we know that at least 15 of the species collected by our students are new records for Belize not present in the national checklist. Many of these species have required identification by taxonomic experts such as Mexican botanist Sergio Zamudio who confirmed the identity of Pinguicula sharpii.

Students have also collected specimens of rare, endemic species . For example, another exciting moment occurred in 2011 when students collected a small herb from the savanna which turned out to be an endemic species in the pipewort family (Eriocaulaceae), Paepalanthus gentlei, previously known from only two collections.

Since 2010 the MSc field course has offered scholarships to enable local students and researchers to join the course. This was mutually beneficial: the Belizean students brought their own experiences, skills and knowledge of local conservation issues to the course, and were then able to take the skills learnt and friendships made into their future studies and careers across Belize and the world. For example, the specimen of Pinguicula was collected jointly by Denver Cayetano, a young forest ecologist from Belize, and Peter Moonlight, who went on to complete his PhD and a postdoc at Edinburgh. Both of these students have gone on to pursue botanical studies and careers, inspired by that one moment on a hillside!

Further Reading:

Goodwin, Z., Stott, G., Ronse De Craene, L., Kay, E., Lopez, G., Haston, E., & Harris, D. (2020). Belize and the RBGE: Reflecting on 16 years of collaborative training. Edinburgh Journal of Botany, 1-19.

Work for this paper was supported by the Edinburgh Botanic Garden (Sibbald) Trust, project 2017#08.