H.J. Noltie

Introduction

While researching the life of John Hope a decade ago I went through the RBGE copies of his personal papers that have fortunately survived in the National Archives of Scotland. The name of one of his correspondents caught my eye, but about whom it was then hard to discover any biographical details. The name was James Badenach and what piqued my interest was not only that the letter was written, in 1779, from Glamis (in my home county of Angus) but that it referred to India, another of my major interests. The topic of the letter was medical, the use of camphor and ipepacuana, and referred to a voyage in 1766 in which Badenach had visited Bombay and been told that camphor could be purchased in Bencoolen or Batavia. Badenach had then just completed a tour of Scotland and intended to return to the East Indies (though this seems not to have happened) and his recent itinerary had included three of the classic sites of the Scottish ‘petit’ tour – Dunkeld, Taymouth and Blair Atholl; it had also taken him to Inverness and Ross-shire leading one to wonder, in connection with his name, if he might have had family connections in the north. (There is an intriguing suggestion on a website with genealogical enquiries that the Badenach name for the Glamis family was an alias for McDonald, which might indicate a Jacobite past that required concealment).

Other references to Badeanch in the Hope papers show that in 1763 he had attended what was only Hope’s third annual course of botanical lectures (but not Hope’s other course on Materia Medica), that Badenach was a correspondent of the London naturalist John Ellis (c 1710–1776) and that in 1774 Hope paid him a shilling for freight of seeds that, as will be seen, probably came from the second of Badenach’s voyages to China. Although Hope’s herbarium has not survived a manuscript catalogue of it has, and in it is a record of Valeriana dioica from Langholm by ‘Mr Burges and Mr Badenoch (sic)’. The Rev John Burgess, minister of Kirkmichael, Dumfries-shire, was a significant contributor to Lightfoot’s Flora Scotica but his connection with Badenach and the reason for the latter’s journey to the Debatable Lands is unknown. Also among the Hope manuscripts at RBGE is a list of plants arranged by flowering-time now known to be the work of Adam Freer and, while unattributed, one wonders if the record in it of ‘Rumex digynus? an [= or] scutatus’ from the ‘Castle of Glammis’ might not have originated with Badenach.

More recently I came across Badenach’s name at Oak Spring, Virginia, in the papers of John Bradby Blake (1745–1773), an East India Company (EIC) official (their bizarre denomination was ‘Supercargo’) based in Canton where he commissioned a series of outstanding botanical paintings from a Chinese artist called Mai Xiu. Between these archival encounters with Badenach I had accumulated odd snippets of biographical information and in April 2017 found his almost illegible gravestone at Auchenblae.

While he clearly led an adventurous life, undertook interesting work, made enough wealth to become at least a ‘bonnet’ laird and establish a dynasty, and met some of the major figures of his day, his obscurity is perhaps due largely to his failure to publish more than three rather insubstantial papers. His one major publication was never intended as such. It appeared as recently as 1992 and fails to do justice to the breadth of his life – its editor didn’t even manage to establish the dates of its author’s birth or death, knew nought of his international travels and therefore could only denote him a ‘Stonehaven farmer’ – one was left to wonder if the admittedly fascinating agricultural diary concerned was the work of the same Dr James Badenach, but so it proved. While what I have been able to discover does not amount to anything very substantial it seems worth setting it down, not only to reconnect the two halves of Badenach, but to show him as an example of a type of enterprising eighteenth-century Scot, steeped in the ideas and ideals of the Enlightenment with its emphasis on useful knowledge, whereby an EIC naval surgeon could contribute to the betterment of man (through medicine) and scientific discovery (natural historical) while at the same time bettering himself through the acquisition of wealth and social status. Coming from a background of prosperous tenant farming he already had at least one foot on the ladder and thus was not quite the classic ‘lad o’ pairts’.

Life and work: The Eastern Voyages

James Badenach was christened in the parish of Kirriemuir on 1 June 1744. In the church register his name was spelt ‘Badenouch’, the first of many alternatives by which he was known during his lifetime, which included ‘Badenough’, ‘Baddenough’, ‘Badenack’, ‘Badenok’ and ‘Badenoch’. (It should be noted that he own spelling was far from orthodox: the fairer sex he spelt not only in the conventional way but as ‘wewmen’ and even ‘wowmen’, the latter doubtless not intended to indicate their potential effect on suggestible members of the opposite sex). At the time of his baptism his (eponymous) father was described as a ‘merchant’ who must later have turned farmer to become tenant of Mains of Glamis. Of the younger James’s education nothing is known until his appearance in Hope’s 1763 class list, after which he became a ship’s surgeon on an EIC ship, the Nottingham. Under the command of Captain the Honourable Thomas Howe this sailed to Bombay in March 1766 returning to Gravesend in November 1767.

An Irish doctor called David Macbride had suggested that ‘wort’, a decoction of brewing malt, might be a remedy for scurvy and the influential London-based medics Sir John Pringle and William Hunter recommended that it be tried at sea. Badenach was one of the disappointingly few naval surgeons to take up the challenge and his report on six case studies (as given in a letter to Hunter from Bombay in October 1766) was reproduced in Macbride’s An Historical Account of a New Method of Treating Scurvy at Sea (1767). Although wort is rich in vitamins of the B complex it does not contain vitamin C so any benefit attributed to its use must have been a result of its making up for other dietary deficiencies suffered by the sailors treated. The real cure for their scurvy can only have been the fresh fruit eaten after the ship reached the island of Johanna in the Comoros Islands between Mozambique and Madagascar. Badenach would himself in 1776 publish a supplementary paper summarising the use of wort, of which he was convinced as to its effectiveness, by other ships’ surgeons. It was on the Nottingham that Badenach used the ipepacuana and camphor reported in his letter to Hope. A second medical paper, published in 1771, also related to a disease he had to deal with on this voyage. Known as the ‘bilious fever’ this was probably malaria, which he took to be caused by night air and contracted when sailors slept on land overnight, a practice therefore to be avoided. His treatments involved bleeding, antimonial medicines and saline, followed by ‘cortex peruvianus’ of which the last (i.e. quinine) must have been the effective agent.

On this first of his three voyages Badenach must have been allowed to engage in private trade and begun to accumulate capital that, following its conclusion, allowed him a three-year spell in Britain. On 11 August 1768 he was awarded an MD by the University of Glasgow, though it is not known why he chose that western place of learning rather than Edinburgh, nor whether he attended any lectures there (for example those of William Cullen). In the same month he had asked Hope for a letter of introduction to the Aberdeen naturalist David Skene in which Badenach was described as ‘my favourite pupil’, which perhaps suggests something deeper than mere flattery. In 1765 it had also been Hope who had provided the introduction to Ellis in which he described Badenach as ‘a young man of a most happy genius’. At the Linnean Society of London are five letters from Badenach to Ellis, in which are to be found revealing biographical details – if tantalisingly scanty. The first two are from a period spent in Paris in the summer of 1769 during which the young surgeon studied literature on birds and quadrupeds in libraries (specifically the works of Linnaeus, Buffon and Brisson) and in the King’s Cabinet in the Jardin du Roi under Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton. In Paris he also met the chemists Augustin Roux and Guillaume-François Rouelle and Henri-Louis Du Hamel du Monceau the great authority on trees (among many other subjects) much quoted by Hope. It was Badenach who showed an engraving of Eriocaulon, the strange aquatic plant recently found on Skye by James Robertson (engraved by Andrew Bell under the name ‘Naysmithia articulata’ after Robertson’s drawing), to Antoine Laurent de Jussieu with Hope’s request for an opinion from the great exponent of the natural system on the plant’s affinities. It is probably from these letters, in which Ellis’s experiments on putrefaction were discussed, that originates the suggestion that, with Ellis, Badenach was the first to consider the role of micro-organisms as a cause of disease (see Ellis’s ODNB article).

During this period in France Badenach was in touch, or correspondence, with four other interesting members of Hope’s international circle: the physician Sir John Pringle, and three former and particularly talented Edinburgh students. Pringle and Theodore Forbes Leith were also in Paris at this time (Leith and Badenach made a joint excursion to Fontainbleau), the American Benjamin Rush was in London and Adam Freer in Aleppo. On return to London Badenach caught up with Pringle and met the chemist Peter Woulfe and the naturalist Anna Blackburne. Doubtless keen to pick his brain about Parisian intellectual life, Hope wanted Badenach to return to Edinburgh but he must already have determined to make another voyage, this time to China. The motivation was doubtless financial, though it would also provide opportunities for further medical and natural historical observations and, with luck, for discoveries.

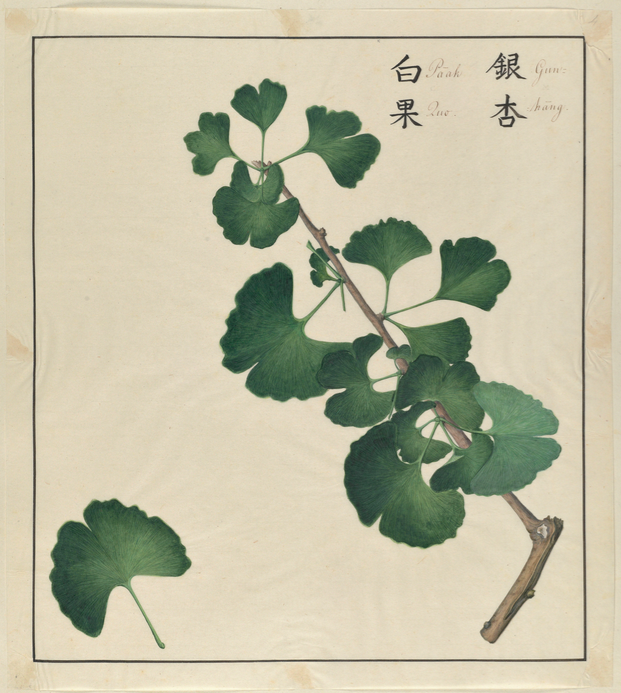

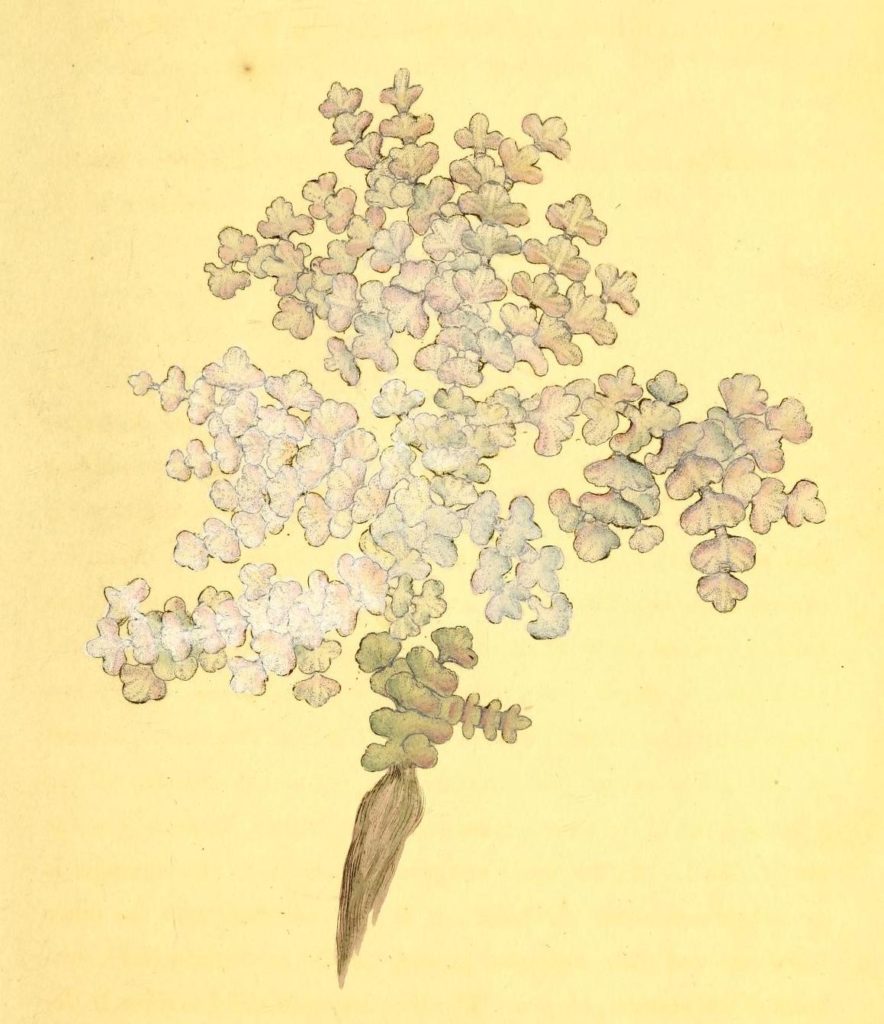

The ship that Badenach signed up with was the 499-ton East Indiaman Princess Royal under the command of Captain Robert Ker(r) (as Kerr died in Cupar, in 1794, a Scottish link is suggested). A painting by John Cleveley the Elder of this handsome ship is in the National Maritime Museum. Badenach was surgeon on both of its two voyages to China – the first left the Thames in February 1770 and sailed via Johanna (where he collected seeds), Madras (reached in July) and Malacca (where he hoped to obtain seed of the mangosteen) to Canton, returning to Britain July 1771 by way of the Straits of Sunda, the Cape of Good Hope and St Helena. During this voyage, as he had been in Paris, Badenach was fortunate to encounter some particularly interesting men. In the Ellis letters are indications that he actually met Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, which must have been either on his outward voyage at Batavia (where the Endeavour was from October to December 1770), or on his homeward voyage at the Cape where Captain Cook’s ship was in March and April 1771. During the three months spent in Canton (up to January 1771) Badenach met John Bradby Blake, to whom he had a letter of introduction from Ellis and he was entrusted with a plant of Ginkgo biloba to take home, presumably for Ellis. The precious plant was still alive by time the Princess Royal reached St Helena, but it is not known if it reached Britain, where the tree had been in cultivation since 1758 but was still a rarity. In China Badenach also met Robert Gordon (d 1771), surgeon to the EIC factory, who was interested enough in botany to have made his own abridged translation of the Hortus Malabaricus. Badenach must have brought other collections back, though some were damaged on the homeward voyage. These included plants for John Fothergill and it was probably on this voyage that he collected for Ellis a coralline alga previously known from Jamaica. In Solander’s 1786 book on Ellis’s collection of zoophytes the Indian Fig coralline (Corallina opuntia, now Halimeda opuntia) is recorded as having been ‘lately found on the shore of Prince’s Island [= Panaitan], in the Straits of Sunda, by Dr Badenach’.

The rouloul bird

The most interesting find of the trip, at Malacca on the outward voyage in August 1770, was avian. On his return to London Badenach, in October 1771, sent a Linnaean-style Latin description of an unknown bird, with an illustration and covering letter, to Dr Matthew Maty which was read to the Royal Society and published in its Philosophical Transactions. Despite his Parisian zoological studies Badenach was cautious – the letter ended with the decidedly limp sentence:

What genus this bird is properly to be referred to I shall not pretend to determine; but if you think this, though but imperfect account, worth the communicating to your Society, you have my leave.

Had Badenach dared to give it a name the bird, now known as Rollulus rouloul, the crested partridge, would have been new to science, but its scientific naming had to wait for a further decade. When the French naturalist Pierre Sonnerat visited Malacca on his way to China he also saw the bird and learned that it was known as ‘La Rouloul’. Sonnerat made a drawing of it (albeit with an inaccurately long tail) that was published in his 1782 account of the expedition – the basis of the bird’s formal description as Phasianus rouloul by Giovanni Antonio Scopoli in 1786. In the years following there was considerable discussion as to the bird’s affinities, variously placed as a pheasant, a partridge or a pigeon, but in 1791 it was given its own genus by Pierre-Joseph Bonnaterre. The bird is native to Burma, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra and Borneo where its status is now officially ‘Near Threatened’ and it is listed in Appendix III of CITES. It is, however, kept in captivity in the West and can be seen, for example, running around the Eden Project.

The male bird, as illustrated by Sonnerat and Badenach, is black with an iridescent greenish back, red legs, a prominent crest of soft, bronze-coloured feathers, and striking bright red markings around the eye and at the base of the underside of the beak. The female is less decorative, greenish with brown wings and no crest, and received much shorter shrift in Badenach’s description.

A question remains as to the anonymous artist of Badenach’s plate as engraved for publication by James Basire. It is possible that Badenach could have stuffed and brought back the male of the pair and chicks that he took on board but which all died en route and that the drawing was made in London, but had he done so a zoologist there would surely have formally named the species. As no artist’s name is given on the plate it seems equally possible that he brought home a drawing made in Malacca and therefore likely to be the work of a Chinese artist. Although such artists are known to have been undertaking botanical commissions for western patrons (such as Blake) at this time, it seems an early date for an ornithological one, but it is similar in style to those produced three or four decades later for William Farquhar, Stamford Raffles and John Reeves. The bird is shown perched on a branch, which could be suggestive of the Chinese artistic practice of depicting birds on a spray of foliage or flowers (observation from nature would, at least during daylight hours, have shown it on the ground). John Latham, in his General History of Birds pointed out a discrepancy between Badenach’s description and his illustration: in the latter a claw is incorrectly shown on the back toe, perhaps another pointer to a Chinese artist. The rouloul article had an afterlife and was translated into French in 1774 and English in 1809. The latter, in the abridgement of the Philosophical Transactions, was probably made by one of its editors, George Shaw, also a student of John Hope. (Shaw himself, in his Naturalist’s Miscellany in 1791, had published John Latham’s name for the species Tetrao porphyrio, the violaceous partridge, accompanied by a rather bad illustration by Frederick Polydore Nodder).

Badenach’s second voyage on the Princess Royal under Captain Kerr was to Canton via Bencoolen. This set sail in December 1772 and returned to Britain in May 1774, but nothing is known of the surgeon’s experiences on this voyage: it led neither to publications nor mentions in the papers of others, other than Hope’s payment of freight for seeds. The projected return to the East expressed to Hope in 1779 appears not to have taken place as Badenach was not the surgeon on the larger (but with the same owner and captain) Princess Royal which sailed to China in 1777 and 1781, nor on any other EIC ship of the period. Presumably he realised that he had already amassed enough capital from three voyages to acquire the wife and landed property to which he aspired.

Stonehaven farmer

The second part of Badenach’s life was very different from the peripatetic one of the first, and seems to have been spent almost entirely in Scotland. On 5 October 1775, in the Parish of Marykirk, Kincardineshire, he made a canny marriage to a laird’s daughter Ann Graham(e); seven weeks later her elder sister Isabel(la) married John Arbuthnott later to become the seventh Viscount Arbuthnott. The sisters’ father had been born William Barclay and owned the estate of Balmaqueen [now Balmacewan] on the north side of the River North Esk between North Water Bridge and Marykirk. The Barclays were an old Aberdeenshire and Mearns family, owning the estates of Mathers, Urie and Johnston as well as Balmaqueen (which they had owned at least since the sixteenth century). However, in 1744, in order to inherit the nearby estate of Morphie from a cousin of his mother, had to change his name to become William Graham of Morphie. There is a curious link here with a later Indian surgeon as Alexander Gibson’s father was, for many years, Graham’s tenant at Hill of Morphie. Graham died in 1776 upon which Badenach and his new wife moved into Mains of Balmaqueen (perhaps her dowry) and his father appears to have followed in their wake.

Around this time James Badenach senior gave up the tenancy of Mains of Glamis and relocated twenty miles eastwards to the Howe of the Mearns – to another prosperous farm called Johnston at Laurencekirk, conveniently close to his son and daughter-in-law. At Glamis he had been a tenant of the Earl of Strathmore and one wonders if he knew the young William Paterson from nearby Brigton whom the Countess sent to collect plants at the Cape of Good Hope. At Johnston his landlord was the Scottish Judge Francis Garden, Lord Gardenstone, a great ‘improver’ who in in 1765 had built the model village of Laurencekirk (and in 1789 St Bernard’s Well in Stockbridge). From the 1803 inventory of James Badenach senior’s will he clearly kept up his Angus connections as his trustees included two Forfarians, a merchant and the surgeon Dr Patrick Key, uncle of Sir David Brewster (and father of Dr Thomas Key a medical colleague of Hugh Cleghorn in Madras).

Badenach’s finances must have prospered for in 1788 he purchased, from Alexander Leith, the larger and already improved estate of Whiteriggs beside the Bervie Water in the parish of Fordoun, which included the farms of Arthurhouse and Suttiewell. This was close to Arbuthnott and therefore to Mrs Badenach’s sister. The estate did not have a mansion, only a large farmhouse, which suggests that for Badenach farming was a higher priority than a showy house, though ownership did entitle style himself as ‘of Whiteriggs’. In 1792 the estate was enlarged with the purchase of the farms of Easter and Wester Waterlair, but some of this additional land was leased out. The diary of agricultural activities and weather relating to Badenach’s land, kept from 1789 until his death in 1797, was published in 1992 under the title Flitting the Flakes [Anglice: ‘moving the hurdles’], when its manuscript was among the archives at Glenbervie House. The editor, Mowbray Pearson, had undertaken little research into Badenach, his concern being farming activities and rural economy, but in the skimpy introduction is the tantalising remark that in an earlier diary Badenach described himself as a member of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh. While he is unlikely to have claimed spurious membership of this significant Scottish Enlightenment body (that in 1783 morphed into the Royal Society of Edinburgh), his name does not appear in its memberships lists as reconstructed by Roger Emerson. The meticulously kept diary suggests that in the final decade of his life Badenach went no further afield than Aberdeen (on ‘County’ business) and Montrose, though he must also have visited Arbroath where he owned the property of Almerie Close, a house and garden on the site of the Almonry of the great Abbey of Aberbrothock dedicated to St Thomas à Becket. The short daily entries, however, are frustratingly devoid of matters of biographical or wider intellectual interest.

Badenach died of ‘dropsy’ and was buried in the kirkyard at Auchenblae (the parish church of Fordoun) on 27 December 1797. According to a notice in the Aberdeen Magazine for January 1798 he died ‘highly respected … for his abilities as a physician, and his integrity as a man’, which suggests that he continued to practise medicine during his Whiteriggs days. His widow Ann lived until 6 August 1815 and their memorial stone was erected by their son, another James, who in 1807 sold Whiteriggs back to the Leiths and thereafter styled himself as ‘of Arthurhouse’. In 1831 the younger James’s son Robert, like his grandfather before him, made a strategic marriage; his wife Anne Wilson was heiress of the Nicolsons of Glenbervie, and the family name became Badenach-Nicolson. It is for this reason that the family archives (and a portrait of Ann Badenach, but sadly not of James) were kept in Glenbervie House until 1979 when the estate passed, through the female line, through Patience Badenach-Nicolson, to her niece Jill Macphie (nee Pearson, her paternal uncle being Mowbray Pearson editor of Flitting the Flakes). At this point the Macphies donated the extensive estate papers (dating back to 1495, including those of the Douglas predecessors of the Nicolsons) to Aberdeen University Library (MS 3021). Due to lockdown these are currently inaccessible, and the online catalogue lacks detail, with no reference to Badenach’s diaries, only to his MD certificate and his appearance in letters from John Ellis and John Hope to David Skene.

Thomas McQuarrie

Hello Mark,

Your article is fascinating!

James Badenach is our ” 5 ” great grandfather (on our dad’s side of the family). James’s daughter, Catherine, married Capt. John Lawson in 1799. David and Walter Lawson, John Lawson’s sons, emigrated to Goderich, Ontario. We are their descendants.

Your article summarizes very well what I have been able to find over the years.

But now I know even more with your findings on his early academic life.

Thank you.

I have always been fascinated by the man because he led such an interesting life.

I have a few reference pieces to James Badenach and Ann Graham ie original Royal Society publication on the Malacca bird, engraved silver bowls, Flitting the Flakes book, etc.

Are you a researcher?

I believe, from past research, that some family portraits were lost in a fire.

All the best,

Regards,

Tom

tmcqua9423@gmail.com

Oakville, On

Canada

Margaret DeLacy

This was a very interesting profile. I perked up when I saw an essay on Dr. Badenach because I tried to learn more about him some time ago without great success. I was interested because the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for Ellis, John (c. 1710–1776), zoologist, states that

” [Ellis} concluded that micro-organisms caused putrefaction some eighty years before Pasteur, to whom the discovery is usually attributed. His microscopes could not resolve bacteria, and he assumed that protists (protozoans) were the cause. He published his findings but poor health prevented further experiments. He and James Badenach MD concurred that micro-organisms might also cause disease: they were perhaps the first in the world to reach this conclusion but their ideas were unpublished overlooked.”

I have not been able to learn more about this, or even track down the source for this conclusion, though presumably it was in correspondence between Badenach and Ellis. The ODNB doesn’t have footnotes, just a list of sources.

Ellis would not have been the first to suggest that some sort of microscopic entity might cause disease but it would still be nice to track this discussion down.

There are a couple of references to Badenach in the edition of John Fothergill’s letters, “Chain of Friendship” ed. Christopher Booth and Betsy Corner (Cambridge:1971).