Elsewhere I’ve admitted to suffering from a condition called beziehungswahn, a mania for making connections. There is a particular satisfaction when the connections made are between divergent and unexpected events, things or people. An example occurred recently with a Lockdown revisit to the British Floras on my bookshelves and a treasured pair of volumes in dark green cloth with gilt lettering.

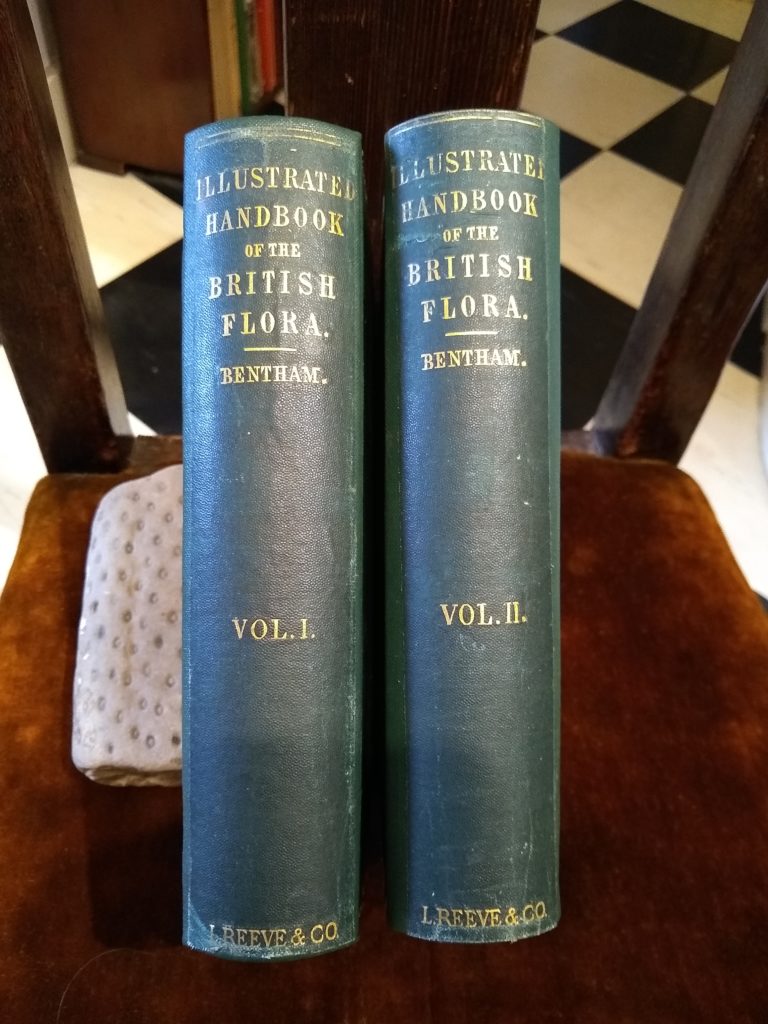

Bentham’s 1865 Illustrated Handbook of the British Flora was effectively the first field guide to British plants, with pictures of every species in the form of delicate black-and-white drawings by Walter Hood Fitch (1817–1892). The copy belonged to my great aunt, May Padman (1892–1968) of Boston Spa and was given by her to my mother Ann Woolliscroft, her botanical protégé. The copy bears copious annotations in a minute and incredibly neat nineteenth-century hand, in which the most frequent locality is Wetherby, my mother’s home village in the West Riding of Yorkshire; the annotator is identified merely by the initials ‘J.S.W.’. A fortuitous discovery during the clearing of my mother’s flat has allowed a most satisfying concatenation between some rather disparate elements among my interests: British plants, childhood botanical haunts, family memories, botanical bibliography, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Victorian church music and hymnody.

To start with the book. George Bentham (1800–1884) was one of the greatest of all the great nineteenth-century botanists, and in the best British ‘amateur’ tradition. He inherited enough money from his philosopher uncle Jeremy to devote his life to botany and never had need to practise his legal training. He assembled a major herbarium, worldwide in scope, which he gave to the nation in 1854, and was a prolific author of Floras and monographs, culminating in the encyclopaedic Genera Plantarum written with his close friend Joseph Dalton Hooker. The first edition of his Handbook in 1858 was unillustrated, but through his work at Kew Bentham must have become acquainted with Fitch’s outstanding botanical artistry. In Glasgow in the 1820s Hooker’s father, Sir William, had ‘discovered’ Fitch as a designer of calico patterns and trained him in botanical technique and practice, in particular the ability to reimagine flattened herbarium specimens into convincingly 3D drawings. He became the major illustrator for Hooker’s extensive floristic publications and travelled south on his patron’s epoch-making removal to Kew in 1841.

Fitch’s 1295 illustrations for the Handbook are exquisite miniatures, a mere 1½ by 2½ inches in size, incorporated with the concise text blocks in a similar way to the woodcuts of the old Herbals. They have often been described as wood engravings, but while clearly made by a relief process the inked lines are far too fine; in any case the engraving of so many wood blocks would have been uneconomical for a relatively inexpensive popular work. The reproductive process used has long puzzled me, but the probable answer is to be found in the remarkable and scholarly book How to Identify Prints by Bamber Gascoigne. W.B. Hemsley, in his obituary of the artist, wrote of Fitch:

in a standing position with a block in one hand and a pencil in the other, he drew without hesitation, and with a rapidity and dexterity that was simply marvellous.

In 1865 Hemsley was Assistant Keeper of the Kew herbarium so must have witnessed the artist at work, though he was inaccurate on the technique, as he referred to the results as ‘elegant little wood-cut illustrations’. By this date, with a mushrooming of affordable book production, and huge technical advances, other means of reproductive engraving were becoming available. Gascoigne describes one such process developed in the 1860s, the ‘graphotype’, which seems the method most likely to have been employed by Fitch. In this a drawing was made on a block of hardened chalk, using a glue-rich ink that bound to the substrate, after which the unbound, not-to-be-printed areas of chalk, could be brushed away. From this relief block, by a two-stage process of electrotyping, a metal block for line printing was made, suitable for juxtaposing with text and hard-wearing for a large edition size. The result was published by Lovell Reeve, a specialist in scientific publications, who owned the Botanical Magazine from 1845 until his death in the year of Bentham’s Handbook. Thereafter the Reeve firm continued to publish many of Kew’s Colonial Floras, not least the great Flora of British India.

The copy of the Handbook in question, as already noted, was given by Aunt May to my mother. I recall it on our Leeds bookshelves in the mid-1960s, though it was not much consulted having been superseded by Hooker’s revision of it as ‘Bentham & Hooker’, which went into seven editions and was still being reprinted by Lovell Reeve and Co. in 1947. For the later editions the Fitch illustrations were reprinted in a separate volume, four to a page, on ‘paper suitable for colouring’. Many owners did so in watercolour and generations of British botanists were raised on ‘Benny Hook’: my mother was given the 1937 printing of the seventh edition by her parents for her fourteenth birthday in 1942. As a child I do, however, remember being intrigued by the annotations in the 1865 volumes, which my mother passed on to me in 1980 while I was working on the Flora of Angus. By this time their bindings were rather tatty and it was the first book that I ever had ‘rebacked’ – by the bindery of the University of St Andrews library.

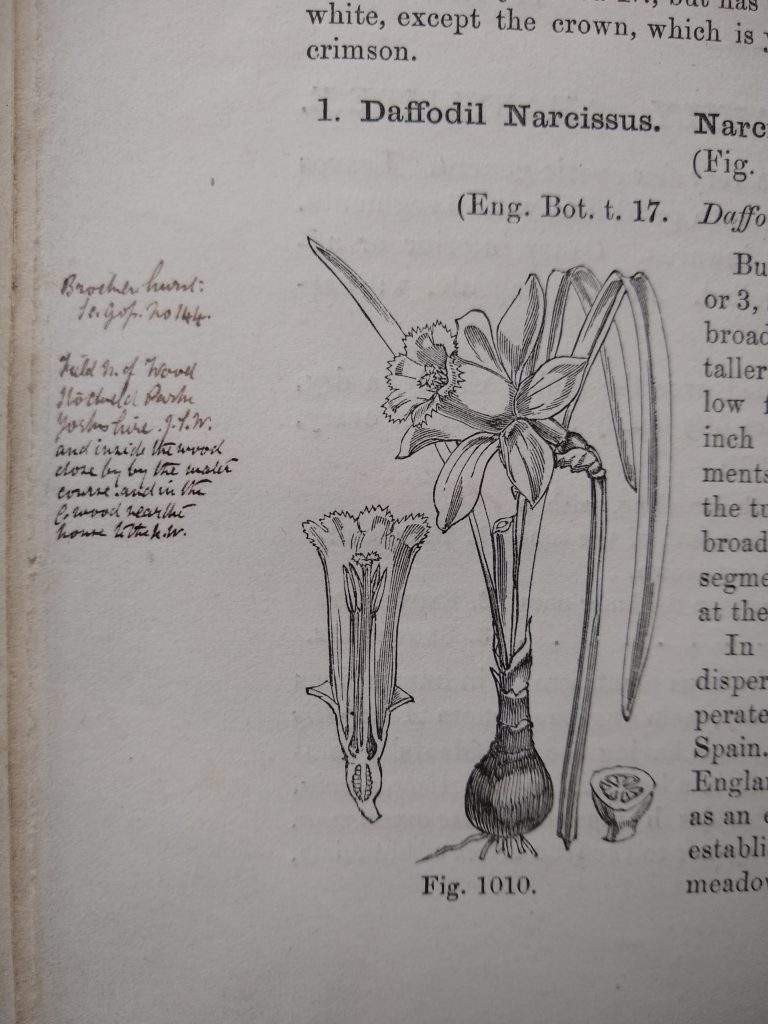

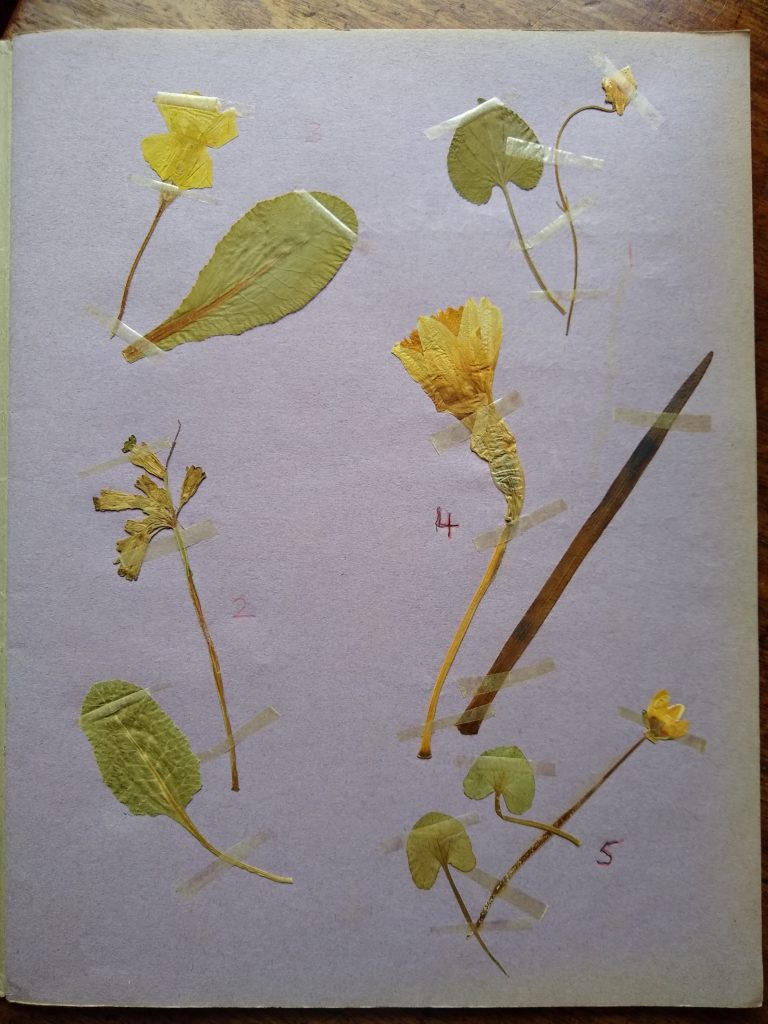

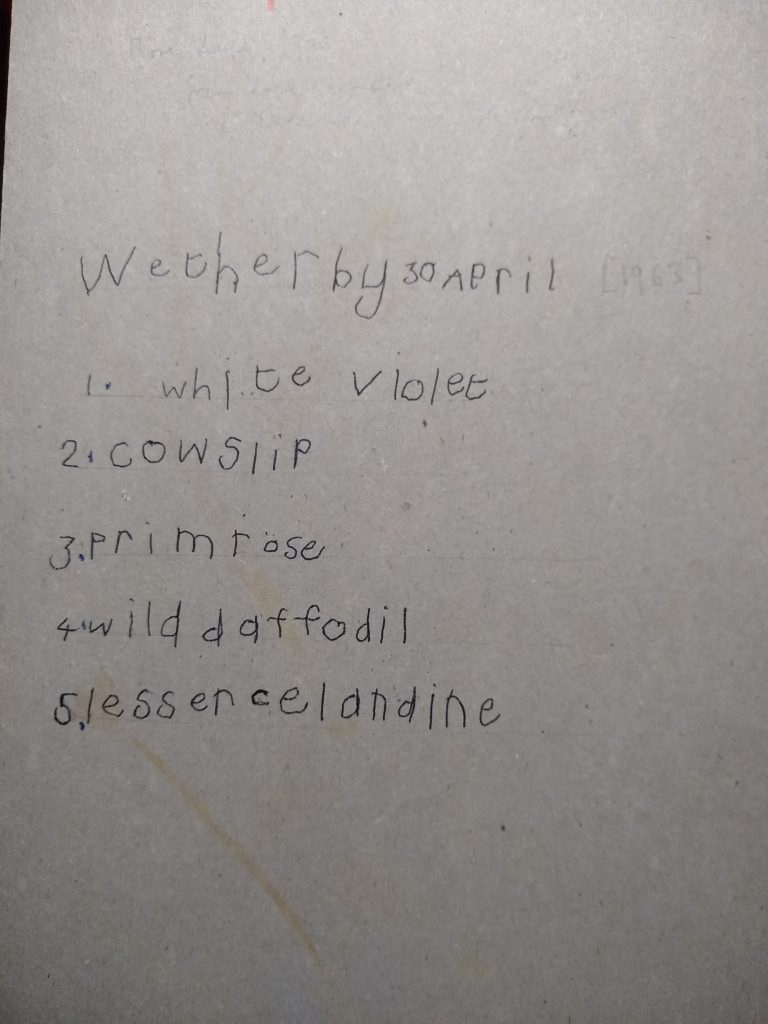

What of the annotations? They occur against 452 of the species entries, of which 342 refer to Wetherby, and a smaller number to the nearby villages of Collingham and Spofforth and the floristically diverse local sites of Woodhall, Linton Common, Askham Bog and Thorp Arch. With a botanical grandmother in Wetherby, and Aunt May and her friends the Kilby sisters in Boston Spa, this rich area of Magnesian Limestone in Lower Wharfedale formed the botanical hunting ground of our childhood. The note beside the wild daffodil Narcissus pseudo-narcissus reads ‘Field N. of Wood, Stockeld Park, Yorkshire. J.S.W.’ 80 years later we would make an annual April pilgrimage to this same locality to see its small, delicately two-toned trumpets. At weekends we would make longer excursions to the Yorkshire Dales – as, apparently, had the author of the annotations, who made records from Upper Wharfedale (from Bolton Abbey and Beamsley up to Grassington and Kilnsey), Swaledale, Nidderdale (Pateley Bridge), and from more distant places including Teesdale and Helmsley.

Narcissus pseudo-narcissus collected at Stockeld Park, Wetherby, 30 April 1963

All of this pointed to J.S.W. as having a base in Wetherby, but two other sorts of records occur. The first appear to be J.S.W.’s own, but made in other parts of England – of these the most frequently mentioned are Winchester and Hampshire (26 records), with a smaller number from the far south-west (including two from Okehampton) and one from Gloucester. The second category is of records not made by the annotator himself – some of these are taken from contemporary literature, others from a small network of correspondents of friends and fellow amateurs. The most frequently cited literature records bear the cryptic reference ‘Sc. Goss.’ or ‘S. Goss’ and include many from Ben Lawers and the Burren of Co. Clare. Aunt May took this to be a botanist, but they in fact refer to the periodical Hardwicke’s Scientific Gossip; smaller numbers are taken from The Naturalist (the journal of the Yorkshire Naturalists’ Union) and from the London-based Journal of Botany; there are also some records from two Floras: C.C. Babington’s Manual of British Botany and H.C. Watson’s Cybele Britannica. On occasion J.S.W. sent puzzling specimens for authentication to the national botanical figures John Gilbert Baker and Hewett Cotterell Watson, to the Oxford bryologist Henry Boswell, and the Leeds botanist Frederic Arnold Lees. Also revealed, from details of flowering times, is his interest in plant seasonality. While only a small number of the notes are dated, these all refer to the single year 1877.

A flat clearance in Dundee and an undated letter

Lockdown delving into my Edinburgh bookshelves coincided with the distressing task of clearing my mother’s flat in Dundee, in which many long-forgotten papers and collections came to light. Among these was a letter from Aunt May, undated as to year, but from c 1965. The Bentham volumes are discussed, as is another annotated pair, Baines’s Flora of Yorkshire, which had yet to be passed on. Aunt May suffered from a serious stroke in 1960, which left her housebound for the remaining eight years of her life. Hiatuses and non sequiturs in the letter reveal a degree of unravelment, but the spirit and means of expression are charming, and remain as testament to her BA from Leeds University from before and during World War I and her subsequent long career as a teacher of English. More significantly, in the present context, the letter reveals the identity of ‘J.S.W.’:

This is not research – it’s frilly Romance – but might be fun till it comes to an end like the cow that grazed into a bog … The present theory is that about 1800 AD, Wetherby was a nest of singing botanists who carolled for the next hundred years, more or less. Evidence?!!! Such as it is: a clutch of names, which may not even be spelt alike … “J.S.W.” was John Sebastian Wesley who practised medicine in W’by and in Spofforth. His particular love was mosses and a debt to him is acknowledged in R. K[ilby]’s copy of a ‘Flora” by somebody called Lee[s].

John Sebastian Wesley (1836–1924)

On seeing forenames shared with the greatest musician ever to have lived, my first thought was that the till-now unknown Wetherby botanist-caroller must have had musical parents. Which hardly prepared me for the information vouchsafed by Google – not only was his father musical, he was Samuel Sebastian Wesley (1810–1876), the greatest cathedral organist and composer of church music in Victorian England. It went further back as SS’s father, Samuel, had been one of the introducers of Bach’s music to England and owned one of the manuscripts of the ‘48’, of which he edited a beautiful edition. I can still remember the excitement of coming upon the E major fugue (not for nothing did Samuel call it ‘Saints in Glory’) in a display case in the old Manuscript Saloon of the British Museum, written in Bach’s beautiful musical hand.

Samuel Sebastian Wesley (1810-1876), By Unknown artist, Public Domain, Link

JSW was the composer’s eldest son and was born on 30 September 1836, when his father was at Exeter Cathedral. This probably accounts for the West Country records among the botanical annotations. In 1842 S.S. Wesley moved to Leeds as organist of the Parish Church, and the six-year old John was sent to the venerable Grammar School (founded in 1552) that I attended from 1965 to 1968. The draw of a venerable cathedral must, however, have proved too great and in 1849 SS moved to Winchester, where he remained until 1865, accounting for many of the records among the annotations. The last of SS’s cathedral appointments, in 1865, was to Gloucester where he died in 1876 and the origin of one of his son’s botanical records.

The younger Wesley trained as a medic at King’s College London, where he matriculated in 1860. He became a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons (1862), obtained a Licence from the Society of Apothecaries (1863) and, in the year that he graduated Bachelor of Medicine, returned to Winchester for practical training. After a period in London as House Surgeon for the St Pancras and Northern District he moved to Wetherby where, by the time of the 1871 Census, he was living as a bachelor, with a housekeeper and a groom. The move to Wetherby was commemorated in 1872 by his father’s composition of a hymn tune named for the village. Wesley held the position of Medical Officer of Health (MoH) for the Wetherby Union and for the First District and Workhouse; he was still in the village in 1888 but at some stage (possibly in 1894 when Dr. J.A. Hargreaves became the MoH) must have returned to the place of his birth as it was in Exeter that he died on 20 July 1924.

Little is known of Wesley’s life other than dry facts taken from his school and university records, the decennial Censuses, various internet sources and from botanical literature. From letters to the ornithologist Alfred Newton he was clearly interested in birds, but, as Aunt May was aware, his major interest appears to have been in bryology. In 1878 he was elected a Corresponding Member of the Manchester Cryptogamic Society and the following year Henry Boswell based the moss Bryum origanum (now B. pallens) on a Wesley specimen from Teesdale; in F.A. Lees’s Flora of West Yorkshire (1888) his name is listed under 73 mosses and 8 liverworts. At one point Wesley’s herbarium was in the Cliffe Castle Art Gallery and Museum in Keighley, and later in the Bradford City Museum, but by 1984 it could not be traced by Douglas Kent and David Allen. There are, however, a few of his specimens in the Manchester Museum and in H.C. Watson’s herbarium at Kew. Had it survived the herbarium might have confirmed, or otherwise, the equivocal evidence from the annotations and his published records, which suggest that his botanical days were limited to the late 1870s and early 80s.

Wesley had not only an interesting musical pedigree, but a distinguished ecclesiastical one. Although his father must have become an Anglican, and John’s brother Charles Alexander (1843–1914) was a Church of England clergyman, his grandfather was the great Methodist hymn-writer Charles Wesley. My grandparents, and for three previous generations, were staunch Methodists. While attending the Wesleyan Chapel in Bank Street, Wetherby in the late nineteenth century, I wonder if my Woolliscroft great grandparents were aware that the great uncle of their MoH was the founder of Methodism, John Wesley? Wesley most probably attended the parish church of St James’s, but might he, or at least his housekeeper, have patronised the Woolliscroft family’s draper’s shop in the village? Such a question, unthought of until now, is likely to remain unanswerable, but who could have known, prior to the discovery of that letter, that on my own bookshelf, and for thirty years, had been standing a direct link with the composer of one of my favourite anthems? While its words remind one of the ephemerality of life on earth (of particular poignance to graminologists: ‘The grass withereth and the flower thereof falleth away’), the anthem ends with an assurance of eternal truths, expressed in triumphant a blaze of E flat major: ‘But the word of the Lord endureth forever’.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Mark Lawley for information from the censuses and GRO deaths; to Peter Wilkie for consulting Medical Directories for me online, and to David Long for putting me in touch with Mark Lawley and Tom Blockeel who also provided helpful information on J.S. Wesley’s biography and bryological records.

References

Boswell, H. (1879). Bryum origanum. The Naturalist 5 (n.s.): 33.

Gascoigne, B. (2004). How to Identify Prints. 2nd ed. London: Thames & Hudson.

Hemsley, W.B. (1915). Walter Hood Fitch, botanical artist, 1817–1892. Kew Bulletin 1915: 277–284.

Kent, D.H. & Allen, D.E. (1984). British Herbaria. London: Botanical Society of the British Isles.

Lees, F.A. (1888). The Flora of West Yorkshire. London: Lovell Reeve & Co.

Manuscript sources (not seen)

Linnean Society of London – 7 Letters from J.S. Wesley (Wetherby 1877– 9) to E.M. Holmes about bryophytes (MS/235/18)

Cambridge University Library – 2 letters from J.S. Wesley (Wetherby 1876) to Alfred Newton Wetherby (MS Add. 9839)

Maura C Flannery

This is a remarkable story definitely displays the benefits of beziehungswahn.