At the Natural History Museum I’ve recently catalogued a collection of 314 botanical watercolours made at the Saharunpur Botanic Garden in northern India between 1843 and 1866 for its superintendent William Jameson (1815–1882).

(Source: https://searchthecollection.nga.gov.au/object/163281)

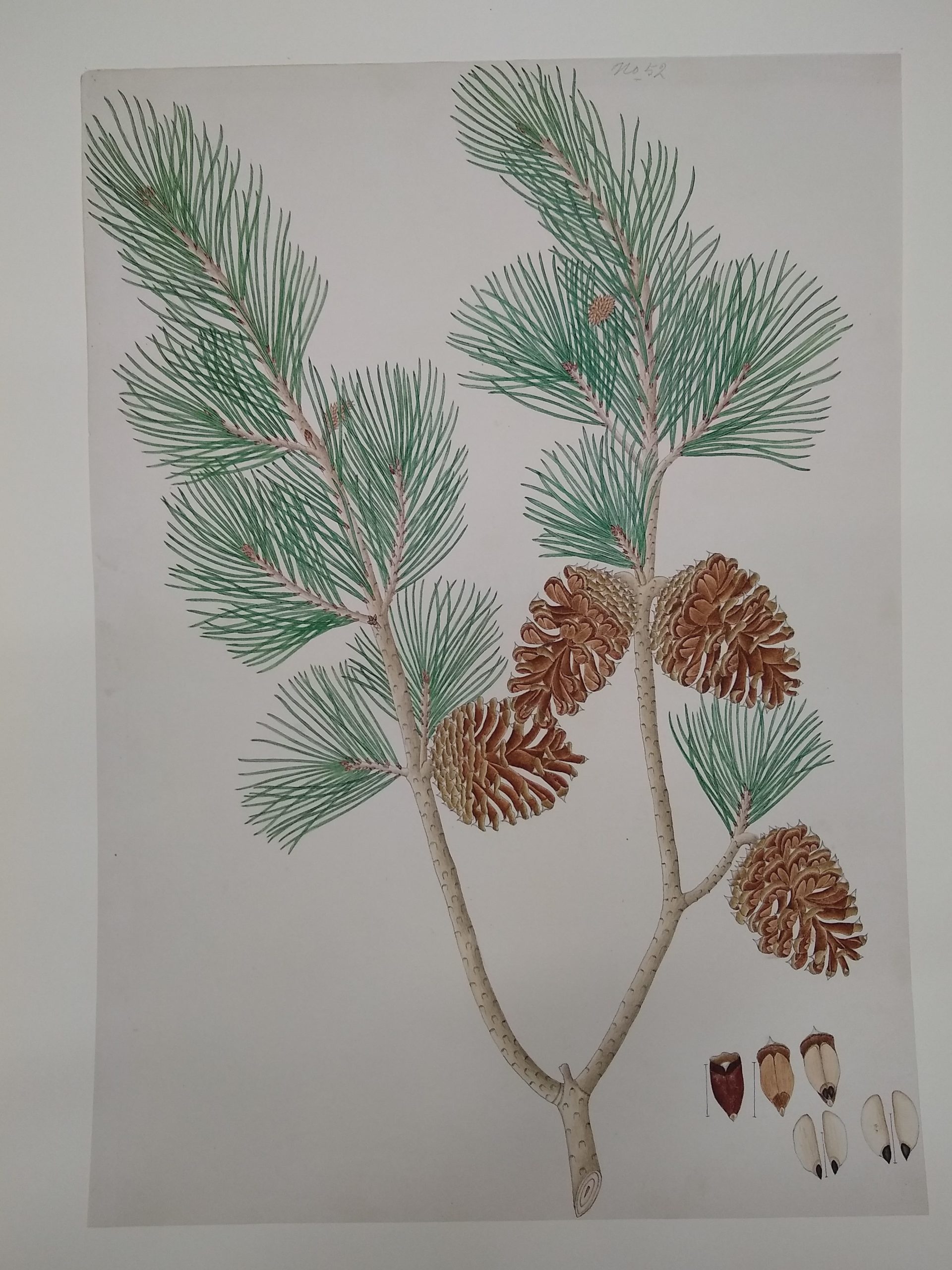

Two of the most intriguing drawings depict a pine. They are labelled as having been collected in Nepal and bear the unfamiliar name Pinus royleana. What took me aback was that with short, paired needles, it was neither of the two known pine species native to Nepal. Pinus roxburghii and P. wallichiana both have much longer needles, the former borne in threes, the latter in fives.

There turned out to be a fascinating story. From ‘Plants of the World Online’, the publication details were quickly established:

Pinus royleana Jameson ex Lindley, J. Hort. Soc. London 9: 52. 1855,

based on ‘seeds, cones, and a few loose leaves’ received from Dr Jameson by the East India Company in London in April 1853, and said to be from ‘a noble tree, growing in Nepal at an altitude of 8–10,000 feet’.

In fact, it is a moot point as to whether or not Lindley’s was the first publication of the species, as Jameson himself published it in the same year, with a validating description (Jameson 1855). On page 43 of his 1855 garden report he wrote that the species had been ‘discovered in 1850 by the Garden Seed collectors on Gossainthan mountain in Nepal at an altitude of 10,000 feet above the sea’. The description is in the introduction: ‘This species, distinguished by the fine dark foliage, and small adherent pendulous cones, armed with strong spies, is well adapted to the open air in Britain, and will no doubt prove a great acquisition to the arboriculturists’.

Since 1858 Pinus royleana has been synonymised with what is now known as P. echinata, an eastern North American species. The back-story is to be found in George Gordon’s The Pinetum (Gordon 1858: 171). The seeds were sent by Jameson to John Forbes Royle, the economic botanist at India House in London, and by him forwarded to John Lindley, Secretary of the Horticultural Society. They were grown on by Gordon, curator of the Society’s garden at Chiswick, where a few germinated under his care:

when the young plants attained a sufficient size, I [Gordon] soon detected an old acquaintance [P. mitis, now P. echinata], and afterwards ascertained that the seeds had been obtained from the Residency Garden at Kathmandoo, where the late Mr Winterbottom had previously observed it a scrubby-looking pine about thirty feet high, and, as he described it to me after his return to England, with leaves in pairs, the length of the Scotch Pine, and with persistent ovate cones about one inch and three-quarters long. Mr Winterbottom could not learn that it was found in a wild state in Nepal, but only that it had been planted, where he found it, in the Kathmandoo Garden several years.

The botanist and traveller James Edward Winterbottom (1803–1854) was in the Himalaya between 1846 and 1849 and it was probably during the earlier part of this period that he visited Nepal, as in 1848 he joined the soldier/engineer Richard Strachey (father of Lytton) on the Tibetan Boundary Commission.

The story is of interest from several points of view – Jameson’s misunderstanding of the tree’s source and that the truth should emerge four thousand miles away in London and several years later. Although the tree turned out to have been collected in a garden, had it been planted in a natural habitat, it could easily have been mistaken for a native. The fact of a North American species of pine having grown to a height of 30 feet in Kathmandu by around 1846 is extraordinary, and the intriguing question remains as to who might have planted it, and the origin of the seed. Could it have been planted by the Hon. Edward Gardner, British Resident from 1826 to 1829, who developed a garden at the Residency? Or by his successor Brian Hodgson between 1829 to 1843? Where could either of them have obtained the seed – via Nathaniel Wallich and the Calcutta Botanic Garden, or through Gardner’s American family connections?

There also remains a question as to the material the two drawings were based on. The smaller one, 198 x 320 mm (NHM Saharupur Collection 188), is dated January 1853 and shows a single cone, a cone scale from above and below, three seeds, a vegetative shoot and a needle-pair (i.e., the sort of material that was sent to Royle). The larger drawing, 339 x 474 mm (NHM Saharupur Collection 190), is dated from the following year, April 1854, and shows a forked branch bearing four cones, with three details of cone scales and four seeds. What had the collectors brought back from Nepal in 1850? Was it the sort of fragments sent to Lindley and shown in the first drawing? In which case, realising it was something interesting, did Jameson send them back to collect the larger specimen drawn in 1854 (which certainly couldn’t have been made from a living specimen at Saharunpore). The branch appears to be drawn life-size, i.e., almost 50 cm long and surely can’t have been made from an herbarium specimen, as the attached cones would be far too bulky to have been pressed. In which case how could the collectors not have remembered where they obtained such a large specimen, one so different from the two native Himalayan pines with which they must have been extremely familiar, and then carried 500 miles back to Saharunpur? Or did they deliberately mislead Jameson over its source, not wanting to admit (for whatever reason) that it came from a garden?

References

Gordon, G. (1858). The Pinetum. London: Henry G. Bohn.

Jameson, W. (1855). Report upon the Botanical Gardens of the Government, North West Provinces. Roorkee: Thomason College Press.

Noltie, H. J. (7 August 2011). “A botanical group in Lahore, 1864”. Archives of Natural History. 38 (2): 267–277. doi:10.3366/anh.2011.0033.

Paramjit

Hi Henry, Great story told in your own inimitable style! Wish to know many more hidden in the cupboards!!

Paramjit