In Spring 2004 a memorable exhibition curated by Carol Armstrong and Catherine de Zegher was shown at the Drawing Center in New York, and later that year at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven. To accompany the exhibition a profusely illustrated, book – far more than a catalogue – was designed by Luc Derycke. This has long been out of print and on the second-hand market current prices range from £121 to £408. (The Kew copy has been removed from the open shelves and stored in the Rare Book Room!). I had forgotten, until revisiting the book recently, just how many of the illustrations included were of Indian botanical drawings – no fewer than 30, more than ten per cent of the total of 245 plates.

I will never forget the excitement of Carol and Catherine on their visit to the library of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) when planning the exhibition. Their eyes almost popped out on stalks when they saw the treasures that we are fortunate enough to care for: illustrations of plants not only from ocean deeps, but from hills and vales, and from the Orient. Similar revelations must have taken place on their visits to collections in London – at Kew, the Natural History Museum and the Linnean Society. As a result of the visit and the subsequent loan request, the contents of the exhibition and book came at the time as no great surprise, as both strayed some considerable distance from the ostensible primary theme – the representation during the early Victorian period of ‘Ocean Flowers’ (i.e., marine algae) by means of herbarium specimens, drawings, nature prints, and images made by early photographic techniques. This huge expansion of scope is especially apparent in Armstrong’s substantial, and substantially titled, essay ‘From natural illustrations and nature prints to manual and photogenic drawings and other botanographs’. In this the author’s purpose was to set the cyanotypes of algae made by Anna Atkins (1799–1871) in the context of a widely interpreted overview of the botanical drawing of her era. Armstrong made no claim that the Indian drawings had any influence on Atkins (most of them at the time were, in any case, locked away in private or inaccessible institutional collections): ‘as these artists were working far away from home, any resemblance between their depiction and Atkins’s cyanotyped ferns and flowers must be fortuitous’. Nonetheless, Armstrong clearly found a deep resonance with ‘the cursive delicacy of the anonymous Indian draftsmen’, which lead to their extensive representation in the exhibition and her essay. It should be noted that, with the exception of the Dapuri drawings, nearly all of the Indian images reproduced date from long before the main focus of the exhibition, which according to de Zegher’s introduction was the period 1839 to 1854 – the Kerr album is from as early as the 1770s.

At the Linnean Society Armstrong and de Zegher focussed on the drawings made for Francis Buchanan in Nepal (but without realising it also in Mysore). Their major interest was in cryptogams, and on their visit to Kew they appear largely to have concentrated on ferns. In 2004 the early Indian drawings, including the ferns, were all scattered among illustrations from other parts of the world in taxonomic order. To complicate matters further there were two such sequences, and kept in two different parts of Kew’s Herbarium and Library complex: the larger, folio-sized, drawings were in the Library; those the size of herbarium sheets on the top floor of Wing D of the Herbarium. In 2004 nobody at Kew knew anything about the nineteenth-century Indian drawings, but between 2018 and 2021 I went through both the ‘folio’ and ‘herbarium’ sequences, extracted the pre-1850 Indian drawings, and reassembled them into their original collections. Only then did it become possible to study them in depth, work out their very varied histories, catalogue them, and give individual drawings accession numbers by which it is now possible to cite them.

Most of the drawings reproduced in Ocean Flowers had therefore already been extracted and put into their original collections; however, on my revisit to the book it became apparent that I had missed some of those chosen for illustration. In December 2023 I therefore revisited the parts of the fern collection that remained in the Herbarium and Library to try to find the remainder. These had been returned to the collections following the exhibition (though their backing sheets still bear tell-tale remnants of paper hinges on the upper margin of their versos). This allowed the finding of one of the ‘Mrs Govan’ drawings, a Brazilian fern by Nathaniel Wallich, and it made me look again at the Michael Pakenham Edgeworth collages that, as the work of a Western artist, I had previously identified but not extracted. Armstrong and de Zegher must have spent considerable time going through these large collections – there two folio and 23 herbarium boxes, containing between them more than 3000 drawings and prints of ferns. That they picked almost exclusively Indian drawings out of these riches is remarkable and, given the theme of the exhibition, inexplicable. Although they did include nine drawings and prints of ferns and seaweeds by Walter Hood Fitch they ignored, for example, the exquisite pencil drawings of ferns by Robert Kaye Greville (1794–1866), which are much closer to the works of Anna Atkins in terms of time, ethos and place.

Most of the drawings for Ocean Flowers were chosen to illustrate the academic themes of the exhibition, but as the basic research on the Indian drawings had not then been undertaken their selection must have been largely on aesthetic grounds and therefore an expression of the personal tastes of the curators. It is of interest that two of the same drawings (the Lasia from the Edinburgh Kerr album; Plate 174 see below) and one of the Parry drawings (Plate 163) were also selected (with no reference to the earlier exhibition) for the ‘Forgotten Masters’ exhibition held at the Wallace Collection in 2019/20 (Dalrymple, 2019: plates 48 and 53). The rationale for the two exhibitions was entirely different (that of ‘Forgotten Masters’ was to focus on the identities of the Indian artists, almost entirely unknown at the time of the earlier exhibition that was, moreover, almost entirely Eurocentric). This duplication doubtless says something about prevailing visual tastes of the early twenty-first century.

East India Company (EIC) Surgeons

My work since 2004 on the collections of the RBGE, the Linnean Society of London (with the help of Mark Watson), the Natural History Museum (NHM) and Kew since 2018, has revealed the identities of the commissioners of two of the previously unknown groups of work selected for reproduction by Armstrong and de Zegher. The spectacular Lasia leaf (Plate 174), the Jak fruit (Plate 172) and the female Phoenix inflorescence (Plate 226) are in an album containing paintings by several distinct hands on the rather surprising support medium of ruled, ledger paper. A manuscript index to the volume dated 1788 proved to be a red herring and by comparison with three volumes of drawings at NHM (with some duplication between the two collections) the commissioner has been identified as the EIC surgeon James Kerr of Crummock (1737–1782). From work on the drawing collection of Dr John Fleming (1746–1829) at NHM it has been shown that the writing of the index is in his hand, and that the volume must have belonged to him in Calcutta following Kerr’s death.

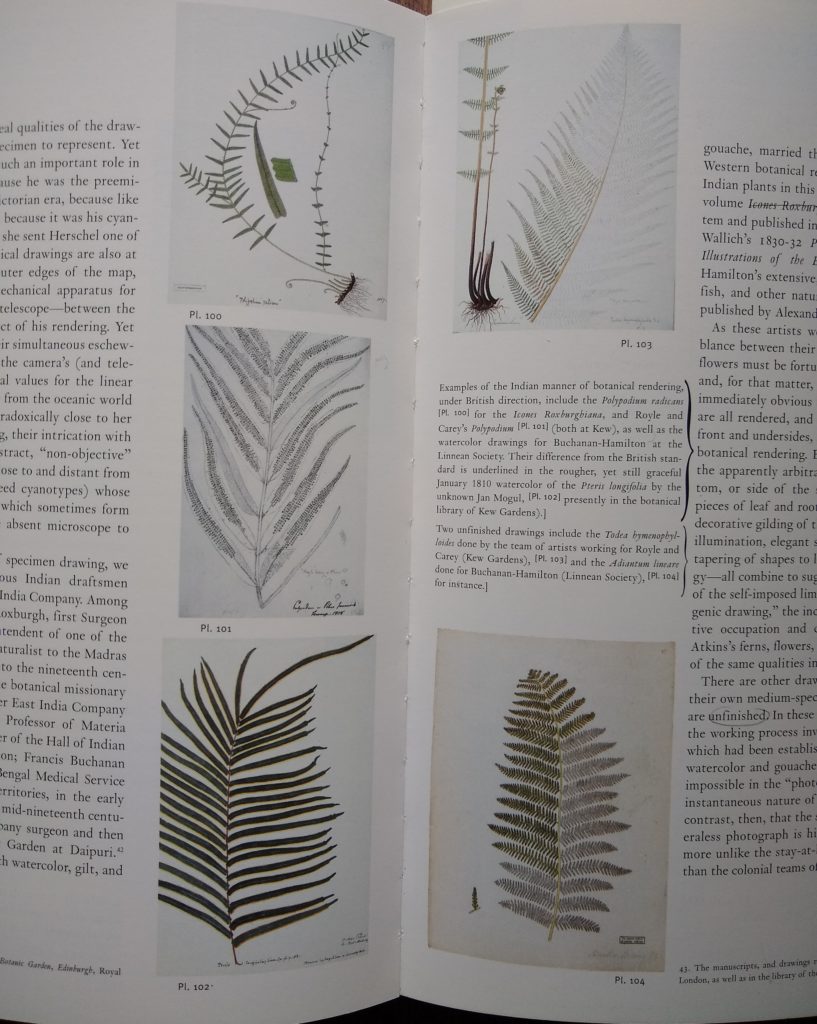

Both Kerr and Fleming were botanical-medical students of John Hope at RBGE, as was Adam Freer (1747–1811). Freer has recently been identified as the commissioner of one of the most distinctive of the Kew collections. Freer went to Bengal as an EIC surgeon in 1781, but, despite his earlier botanical work in Syria, almost nothing was known about any continuation of it in India. The collection is of at least 400 drawings, about half of them unique among Indian botanical art for their stylisation and an often strangely symmetric arrangement of the plant. These are the earliest, probably date largely from the 1790s, and the work of possibly two artists but unsigned. In the last three years of his life, between July 1809 and April 1810, Freer recruited a new group of seven artists, whom he named individually on their drawings – their style is more conventional and painterly and they probably came from Patna. Five were Hindu and used the name Lal; two were Muslim. The name of by far the most prolific of the latter, responsible for almost 70 works, is recorded in a puzzling transliteration as ‘Mogul-Ian’; it was one of his works that was chosen for the exhibition (Plate 102).

Two much better-known collections of Indian botanical drawings from the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were also commissioned by former students of John Hope: William Roxburgh (1751–1815, to be discussed below) and Francis Buchanan (1762–1829, later Buchanan Hamilton). The Buchanan examples chosen turn out, entirely coincidentally, to come from three of the four major ‘statistical surveys’ that he undertook during his Indian career between 1795 and 1814: Mysore (Plates 170, 173, 225), Nepal (Plates 104, 168, 169, 227) and Bengal (Plate 166) – all possibly the work of the Bengali artist Haludar (Noltie & Watson, 2019).

The Calcutta Botanic Garden

Until recently the best-known collection of Indian drawings at Kew was what are known as the ‘Roxburgh Icones’, which were separated from the general illustrations collection and catalogued by J. Robert Sealy in the 1950s (Sealy, 1956). This was because of the taxonomic importance of many of them as authentic material (‘types’) of new species described by Roxburgh, the ‘father of Indian botany’. Roxburgh started to commission Indian artists when he worked on the Coromandel Coast (present day Andhra Pradesh) from the mid-1770s, but continued his programme after moving to be Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanic Garden in 1793. The drawings were made to accompany written plant descriptions, and he had two (sometimes more) versions of each drawing made by the artists whose names he regrettably never recorded. One set of what finally amounted to around 2500 drawings was sent to the EIC headquarters in London and later (1858) transferred to Kew; Roxburgh’s own set was retained in Calcutta and survives at what is now the A.J.C. Bose Indian Botanic Garden, Howrah (Sakhinala, 2019). Three of the Roxburgh drawings were selected for the exhibition (Plates 100, 178, 179), all ferns, although these form only a small proportion of the whole collection.

The second largest collection of Indian drawings at Kew has remained confused until very recently. This is the material transferred there in 1879 as a result of the final breakup of the India Museum and Library. Some 1791 of these drawings bear a cryptic pencil inscription ‘Royle, Carey & Others’. This turns out to be a catch-all handle of which the only accurate part is the name Royle, as the collection does contain many drawings commissioned by John Forbes Royle (1798–1858) (see below). However, it has also turned out to contain the original drawings made for Buchanan on his Bengal Survey of 1807–14, the survival of which was previously unknown (Plate 166 shows one of these).

By far the largest part of the ‘Royle, Carey & Others’ collection, however, consists of drawings commissioned between about 1817 and 1828 by Nathaniel Wallich (1786–1854) while superintendent of the Calcutta Botanic Garden (Plates 103, 167, 179). He inherited Roxburgh’s artists and appointed many new ones. These drawings were taken by Wallich to London in 1828, from which almost 300 were selected for publication in the three lavish folio volumes of his Plantae Asiaticae Rariores, illustrated with hand-coloured lithographs, on which the names of his two master artists, Gorachand (d 1826) and Vishnu Prasad (fl 1805–1832), are given.

One exciting discovery emerged when the drawing reproduced as Plate 101 was recently rediscovered (with a companion) at Kew. Even in the tiny reproduction in Ocean Flowers the date 1808 was visible, which was puzzling as it significantly predates Wallich’s main body of commissioned work. The answer is that it was almost certainly drawn by Wallich himself from a dried fern specimen that he had collected in Brazil in July 1807, on his outward voyage from Copenhagen on the Prince of Augustenburg (Sterll, 2022).

When planning to visit Britain on furlough Wallich commissioned a set of fine drawings from his best artists (by this time the head painter was Vishnu Prasad, but Lutchman Singh probably also had a major hand), based on his ‘working collection’, to present to the EIC on his arrival in London in 1828. This is known as the ‘Wallich 1828 Collection’ (Plate 165) and contains some of the finest botanical drawings ever made.

The other botanic gardens – Saharunpur and Dapuri

Two of the drawings reproduced in Ocean Flowers are credited to ‘Mrs Govan’. These come from a collection of almost 400 drawings, which bear a printed label stating they were painted by Mrs George Govan (née Mary Maitland), c. 1825–32, and presented to Kew in 1904 by two of her sons. When reassembled the collection was found to have originally formed three volumes (there are three sets of identical numbers). The earliest of these proved to have been commissioned significantly earlier than the dates on the label, and by the man yet to become her husband. Dr George Govan (1787–1865) was the first superintendent of the Saharunpur Botanic Garden in Upper India between 1817 and 1821 and the drawings of one of the albums are due to him. The Bengal Government had not allowed the employment of an artist as he had requested, but letters to Wallich, and a few crude copies of drawings sent with these, show that at his own expense (40 rupees per month) Govan employed an artist during his superintendentship, if a not very skilled one. Govan returned on a long leave to Britain from 1821 to 1825, during which he married Mary Maitland (1794–1846), who, like many young ladies of the Scottish gentry, was a competent painter.

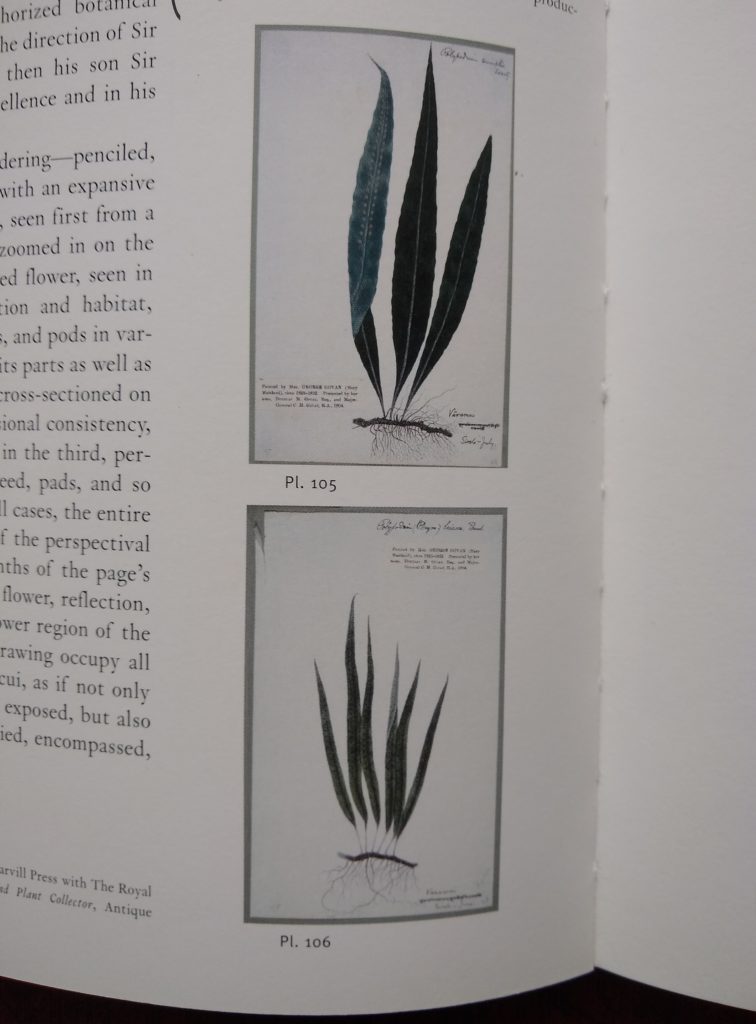

The couple returned to India, and it is from this period that the other two albums date. Some of the drawings in one of these bear Mary’s initials, and some those of her sister Margaret Louisa. However, despite what her sons believed and in which they were followed by Carol Armstrong, the vast majority of the drawings in the later two albums are clearly the work of perhaps two exceptionally gifted Indian artists. These were probably recruited by the Govans in Simla, where most of the drawings of these later albums were made, between 1826 and 1831. Armstrong claimed that Mrs Govan deliberately mimicked the style of an Indian artist. While it must be admitted that it is extremely difficult to be certain whether some of those drawings that are not highly finished, including these two ferns (Plates 105, 106), are the work of one of the Indian artists or of Mrs Govan herself, in these cases I incline to the former. It seems very unlikely that she would have got an Indian clerk to annotate her drawings with a place and date rather than writing it herself in English, and far more likely that the drawings with Hindi annotations (the large majority, including this pair) were both painted and inscribed by an Indian artist.

Govan’s successor as superintendent of the Saharunpur Botanic Garden was John Forbes Royle (1799–1858). When Wallich left Calcutta in 1828 he lent five of his artists (Vishnu Prasad, Lutchman Singh, Rajbullub, Bhaguban and Bhooeekunt), presumably the most senior, to Royle in Saharunpur, where they remained until May 1833. After Royle’s departure in 1831 the artists came under the direction of Royle’s successor Hugh Falconer (1808–1865) who fortunately wrote the artists’ names on the drawings. In fact Falconer named seven artists, two of whom, Kureem Bux and Cassim Ali, may have been recruited locally and been trained under the Calcutta artists. The high quality of the fern (Plate 164), strongly suggests that it is the work of one of the Calcutta team, such as Vishnu Prasad or Lutchman Singh.

Calcutta and Saharunpur both came under the Bengal Presidency, but the Bombay Presidency also had a small botanic garden at Dapuri near Poona (now Pune). From 1838 to 1860 this was under the superintendence of Alexander Gibson (1800–1867) who had studied botany at RBGE under Hope’s successor, Daniel Rutherford. A collection of 173 drawings at RBGE, though how they came there remains unknown, proved to be drawings commissioned by Gibson from an un-named Indo-Portuguese artist between 1847 and 1850 (Noltie, 2002). Their style differs greatly from that of any other Indian botanical drawings, and I have suggested that the artist may have had a technical background such as a map maker. About half the collection depicts native Indian species, many of them plants that Gibson might have introduced to the garden from the tours he made as Bombay’s first Conservator of Forests – these include an aroid (Plate 171) and a sheet with two species of ginger (Plate 229). The other half show exotic species introduced to the garden from a wide range of sources as having possible horticultural or economic potential, including a South American cactus (Plate 228).

Private commissioners

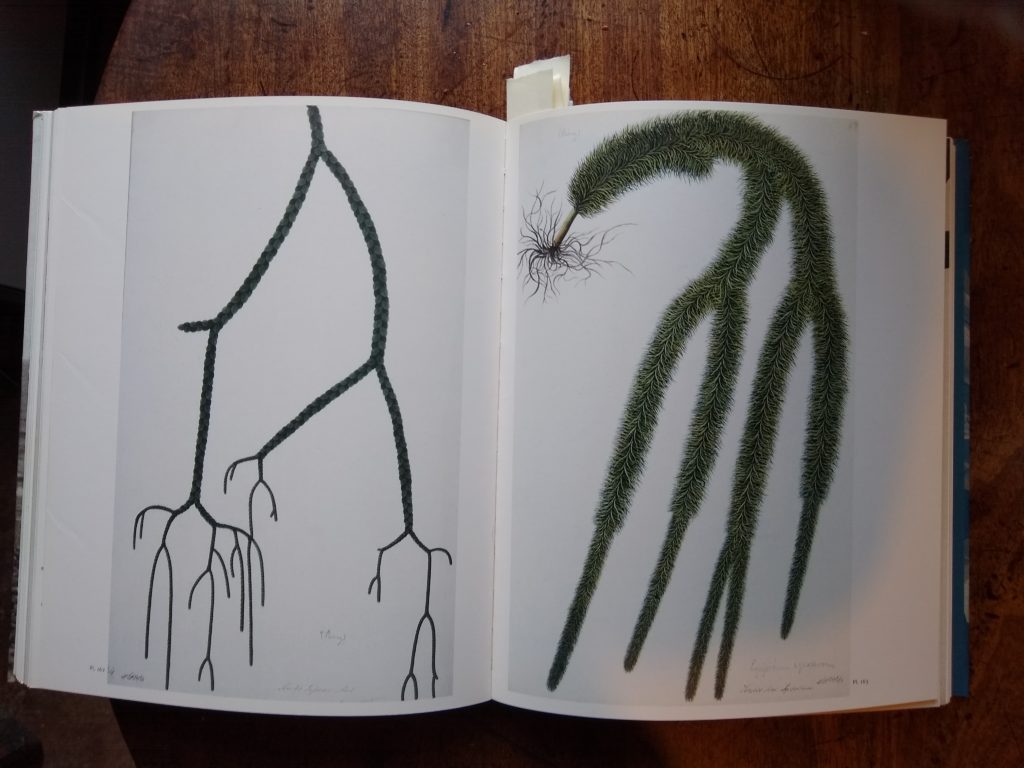

In contrast to work commissioned by the surgeons, and therefore to some extent official EIC commissions, private individuals also patronised Indian artists to make botanical drawings. Two such collections are represented in Ocean Flowers. Richard Parry (1776–1817) was a Bengal civil servant, who in 1807 was posted to Bencoolen in Sumatra, where the Company had spice plantations. Parry took an artist with him who, very unusually, signed his plates, in exquisite nastaliq script that in translation reads ‘The painter of this picture is Manu Lal, artist, an inhabitant of Azimabad [Patna]’ (Archer, 1962) (Plates 162, 163).

William Munro (1818–1880) was a professional soldier, who ended up a General, and saw active service in the Crimean War. He was not in one of the EIC’s own regiments, rather, with the 39th (Dorsetshire) Regiment of Foot of the British Army, which in the 1830s and 1840s was stationed in India. Munro took a keen interest in plants, especially grasses. His first use of an Indian artist (not a very good one) was when he was stationed in Bangalore in the south. But after moving to northern India, he employed in Agra an artist called Gopalchunder, to whom the drawing reproduced (Plate 177) can confidently be attributed, and dated to c. 1845. The date 1880 on the drawing is misleading and is when Munro’s collection of drawings, prints and herbarium specimens were received by Kew.

Nature Prints

Direct prints made from dried plant specimens have a history dating at least back to the European Renaissance, but enjoyed a revival in the mid-nineteenth century when new, more sophisticated, techniques were devised. Many nature prints are reproduced in Ocean Flowers, of which eleven were made and published in India. These, though made using a fairly simple process, are dramatic in terms of composition and in some cases colour, and are the work of European artists: Henry Smith in Madras (Plates 156, 203–5) and Johann Jakob Hunziker in Mangalore (Plates 157, 158, 198–202), and do at least date from the 1850s.

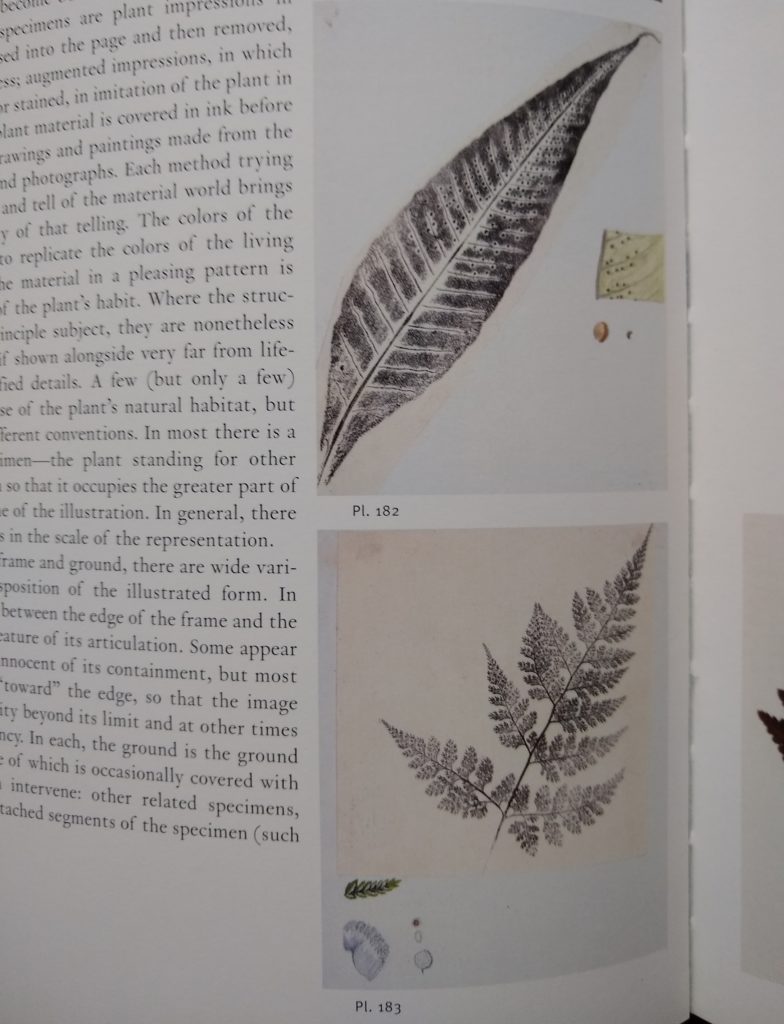

Unknown in 2004 was the authorship of two fascinating collages (Plates 182, 183) comprising a rich, black nature print with supplementary details in delicate watercolour. These are now known to have been made at Hathipaon near Mussoorie in the Western Himalaya in 1838, by Michael Pakenham Edgeworth (1812–1881). Had this information then been available it would doubtless have been of great interest to the exhibition curators for his relationship (half-brother) to the novelist Maria Edgeworth, and for his early forays into photography. The watercolour details must have been made with the optical aid of a microscope.

Revised Captions to the Indian Plates in Ocean Flowers

Even at the time of publication of Ocean Flowers it was clear that some of the plate captions were wrong. Others have been shown to be inaccurate as a result of research undertaken by the author on the Kew, Linnean Society, NHM and RBGE collections over the two intervening decades. Quite by accident, the selection covers a remarkably wide range of the sorts of material commissioned from Indian artists by EIC surgeons, army personnel and civil servants, but also by private individuals. My own interest in these collections has combined art-historical and taxonomic approaches, with a particular interest in their ‘Indian-ness’ – especially the artists who made them. In retrospect it was fascinating to see such work viewed from a completely different art-historical perspective and context, but given how widely admired and cited the book has been, it seems worthwhile even at this late date to publish corrections and to provide additional information (many are neither anonymous, nor undatable), including modern identifications of the plants depicted.

In the following listing the original caption is given first, followed by corrections, additional information, the Kew accession number and the current name of the plant depicted.

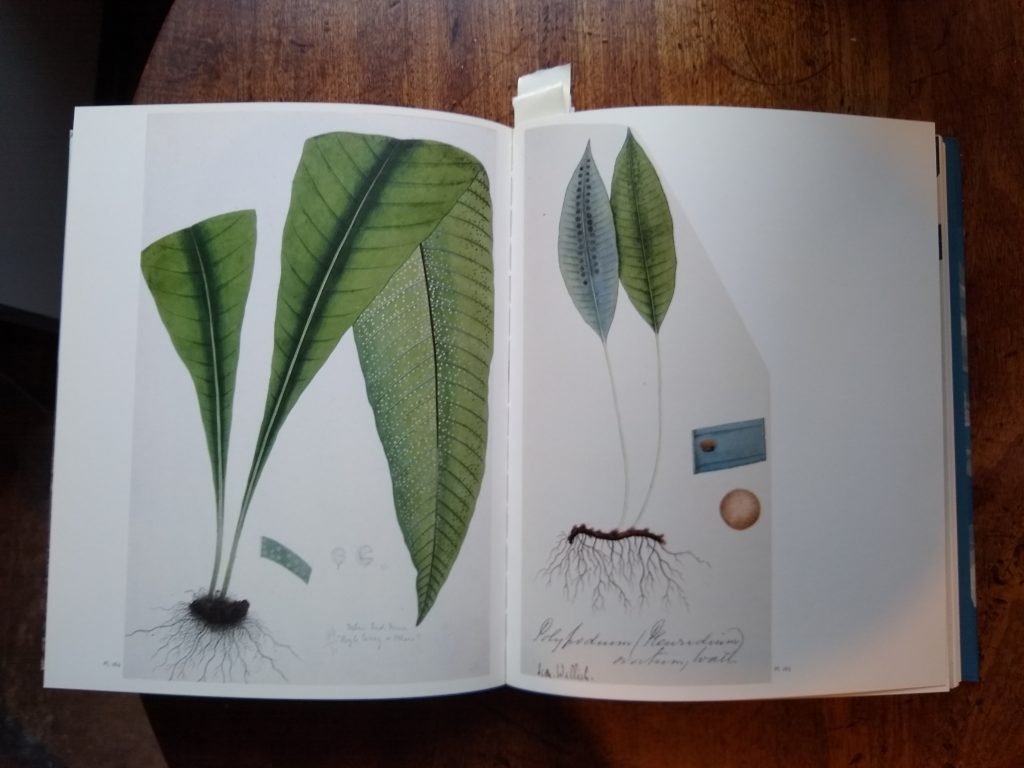

Pl. 100. Anonymous, copy of Polypodium Radicans, Icones Roxburghianae, from Icones Plantarum Indiae Orientalis, 1838–53. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

An un-numbered drawing from the duplicate set of the Icones commissioned by Roxburgh and sent to London. As the plant depicted is from Bengal and ‘shady places around Calcutta’, it must date from Roxburgh’s Calcutta period between 1793 and 1813. The reference ‘Icones …. 1838–53’ is an erroneous insertion and refers to the title of a multi-volume work published in Madras by Robert Wight (Noltie, 2005). Although some of the Roxburgh Icones were lithographically reproduced in that work none of Roxburgh’s ferns were.

RBG Kew, Roxburgh Icones ‘1007. Polypodium proliferum Roxb.’.

= Thelypteris prolifera (Retz.) C. F. Reed

Pl. 101. Anonymous (Collection of John Forbes Royle, William Carey, and others), Filices Polypodium, 1808. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

The drawing is annotated by Nathaniel Wallich: ‘Polypodium e Rhio [sic] Janeiro. Seramp. 1808’. One of a handful of plants collected by Wallich at Rio de Janeiro in July 1807 on his outward voyage from Copenhagen. Made after he reached the Danish colony of Serampore it is probably one of his own drawings, and based on a herbarium specimen that survives in the ‘Wallich’ [East India Company] Herbarium Kew, under the Wallich Catalogue number 307.

RBG Kew, WRCO 833. Also in the Kew collection, on a separate sheet, is the drawing of the upper part of the same frond (WRCO 834).

= Serpocaulon triseriale (Sw.) A.R. Sm.

Pl. 102. Jan Mogul, Pteris longifolia, 1810. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

Painted by Mogul-Ian for Adam Freer in January 1810, probably at Berhampur, Bengal.

RBG Kew, AFCf.359

= Pteris longifolia L.

Pl. 103. Anonymous (Collection of John Forbes Royle, William Carey, and others), Todea hymenophylloides, date unknown. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

Made for Nathaniel Wallich at the Calcutta Botanic Garden between c. 1817 and 1828, by one of the Garden’s team of artists. No collecting details known.

RBGE Kew, WRCO 807.

= Leptopteris hymenophylloides (A. Rich.) C. Presl

Pl. 104. Francis Buchanan Hamilton, Adiantum lineare, from Plantarum Nepalensium Icones Pictae, 1802–1803. Linnean Society of London

Made for Francis Buchanan in Nepal in 1802–3, possibly by Haludar. Collecting details given only as ‘Upper Nepal’.

Linnean Society of London, LS 401D/1/83.

= Dennstaedtia appendiculata (Hook.) J. Sm.

Pl. 105. Mrs. George Govan, 1828–32. Polypodium simplex. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

Probably by an Indian artist, painted for Mrs Govan in Simla. From Govan Album 3 (no. 117), 1826–31. Annotated in Hindi script: ‘Vāramni, Simla – July’ (translator unknown).

RBG Kew, GC3. 157

= Lepisorus scolopendrium (D. Don) Mehra & Bir

Pl. 106. [Mrs. George Govan, 1828–32]. Polypodium lineare.

Probably by an Indian artist, painted for Mrs Govan in Simla. From Govan Album 3 (no. 108), 1826–31. Annotated in Hindi script: ‘Varamni, Simla – June’ (translator unknown).

RBG Kew, GC3. 85.

= Dicranopteris lineare (Burm. f.) Underw.

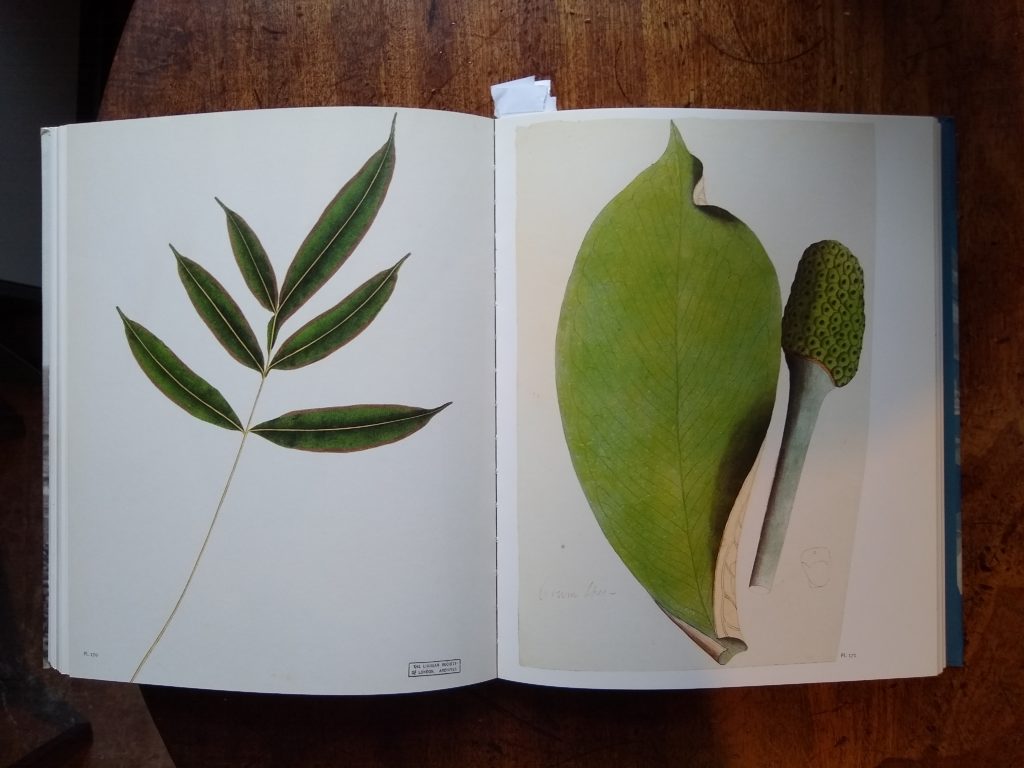

Pl. 162. Anonymous (Collection of Richard Parry), date unknown, Limbo lycopodium (Lycopodium squarrosum) [referring to 163, but misread]. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

Made for Richard Parry at Bencoolen, Sumatra, between 1807 and 1811, signed by Manu Lal ‘painter of Azimabad’. The annotation reads ‘Simbo tapoan. Mal. [i.e. in the Malay language].’

RBG Kew, RPCf. 27.

= Phlegmariurus nummularifolium (Blume) Ching

Pl. 163. [Anonymous (Collection of Richard Parry), date unknown], Lycopodium tapoon (Lycopodium) [referring to 162, but misread]. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

Made for Richard Parry at Bencoolen, Sumatra, between 1807 and 1811, signed by Manu Lal ‘painter of Azimabad’. The annotation reads ‘Simboo. Mal. [i.e. in the Malay language] Lycopodium’

RBG Kew, RPCf. 36.

= Huperzia squarrosa (G. Forst.) Trevison

Pl. 164. [Anonymous, Collection of John Forbes Royle, William Carey, and others, date unknown]. Filices polypodium.

Made for J.F. Royle by one of the team of Calcutta Botanic Garden artists, who were lent to Saharunpur between 1828 and 1833.

RBG Kew, JFRCf. 607.

= Microsorum membraceum (D. Don) Ching (det. C.R. F.-J.)

Pl. 165. Icones Wallich, Polypodium (Pleuridium), date unknown. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

Annotated ‘Polypodium (Pleuridium) ovatum, Wall. Icon. Wallich’. Painted shortly before 1828 by one of the Calcutta Garden artists. Probably based on a drawing made in Nepal in 1821; a related specimen in the Wallich Herbarium (Wallich Catalogue number 276) was collected at Chandaghiry, Nepal.

RBG Kew, W1828 194B (detached from W1828 194A, which is of Pronephrium triphyllum).

= Neocheiropteris ovata (C. Presl) B.K. Nayar & S. Kaur

Pl. 166. [Anonymous, Collection of John Forbes Royle, William Carey, and others, date unknown]. Ceterach indivisa.

Made for Francis Buchanan on the Bengal Survey of 1807–14, by Vishnu Prasad or Haludar. The drawing may relate to a specimen collected at Nibari, Assam, on 26 November 1808 (Wallich Catalogue number 9.2)

RBG Kew, BHBCf.1.

= Colysis pedunculata (Hook. & Grev.) Ching

Pl. 167. [Anonymous, (Collection of John Forbes Royle, William Carey, and others), date unknown]. Polypodium.

Made for Nathaniel Wallich at the Calcutta Botanic Garden, c. 1817–28, by one of the Garden’s team of artists. The origin of the specimen on which it is based is unknown; the fern is widely distributed from Assam eastwards to China and Southeast Asia.

RBG Kew, WRCO 802.

= Neocheiropteris zippelii (Blume) Bosman

Pl. 168. Anonymous Indian Artist (Collection of Francis Buchanan Hamilton), from Plantarum Nepalensium Icones Pictae, 1802–1803. Polypodium maculatum [erroneous caption]. Linnean Society of London.

Made for Francis Buchanan in Nepal in 1803, probably by Haludar. A related herbarium specimen at NHM lacks details other than ‘Buchanan’ and ‘Napaul’.

Linnean Society of London, LS 401D/1/46.

= Euphorbia fusiformis Buch.-Ham. ex D. Don

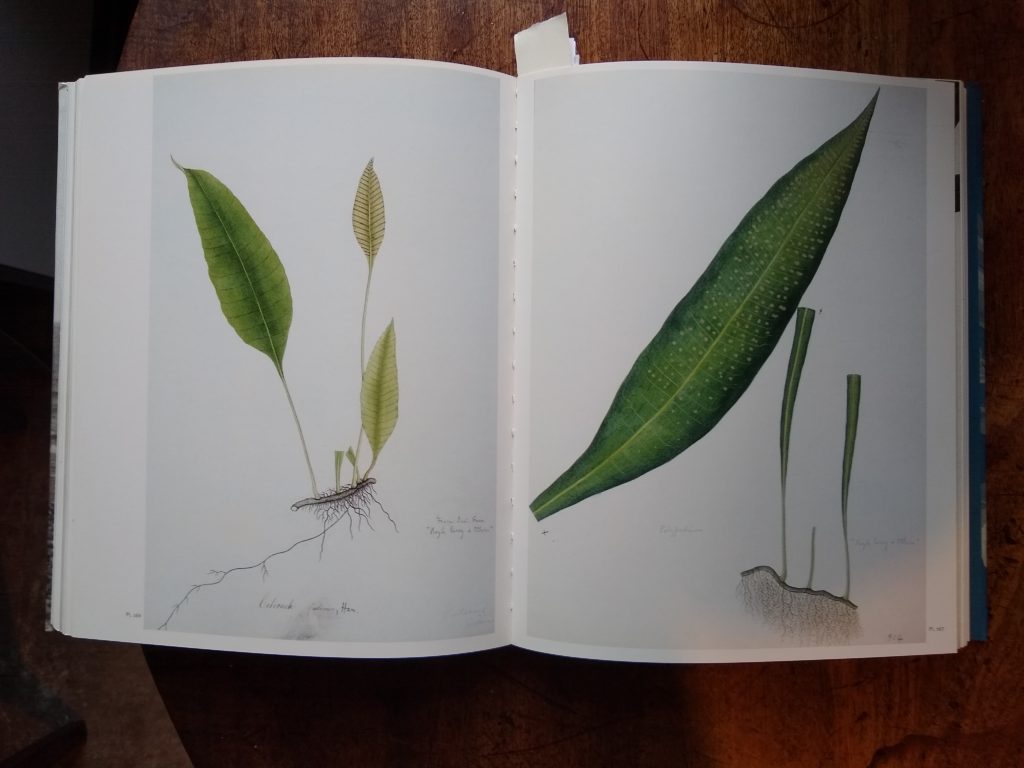

Pl. 169. [Anonymous Indian Artist (Collection of Francis Buchanan Hamilton), from Plantarum Nepalensium Icones Pictae, 1802–1803]. Pilcusta sylvatica. Linnean Society of London.

The original annotation reads ‘Jilcusta sylvatica’. Made for Francis Buchanan in Nepal in 1803, probably by Haludar. A related herbarium specimen in the Linnean Society was collected at Narainhetty, 16 March 1803.

Linnean Society of London, LS 401D/1/19.

= Campylandra aurantiaca Baker

Pl. 170. [Anonymous Indian Artist (Collection of Francis Buchanan Hamilton), from Plantarum Nepalensium Icones Pictae, 1802–1803]. Pteris latifolia. Linnean Society of London.

Made for Francis Buchanan, probably by Haludar, but on his Mysore expedition of 1800/1 and not, as stated, on the later one to Nepal. The fern was collected by Buchanan in the forests of Concan (i.e., coastal Karnataka) in February/March 1801.

Linnean Society of London, LS MS 402D/100.

= Pteris venusta Kunze

Pl. 171. Anonymous Portuguese-Indian Artist. ?Arisaema sp. [Arum sp.], c. 1848. Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh.

It is impossible to say what this is, other than a member of the family Araceae, but possibly belonging to the genus Arisaema.

RBGE, Dapuri Drawing No. 85.

= ?Arisaema sp.

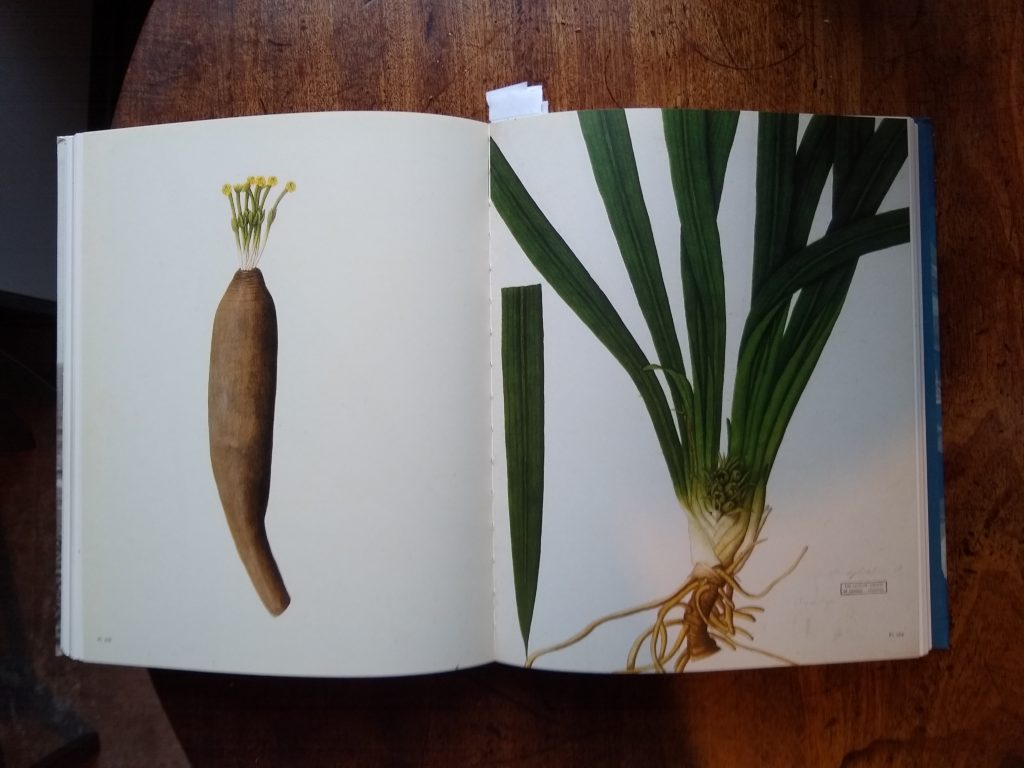

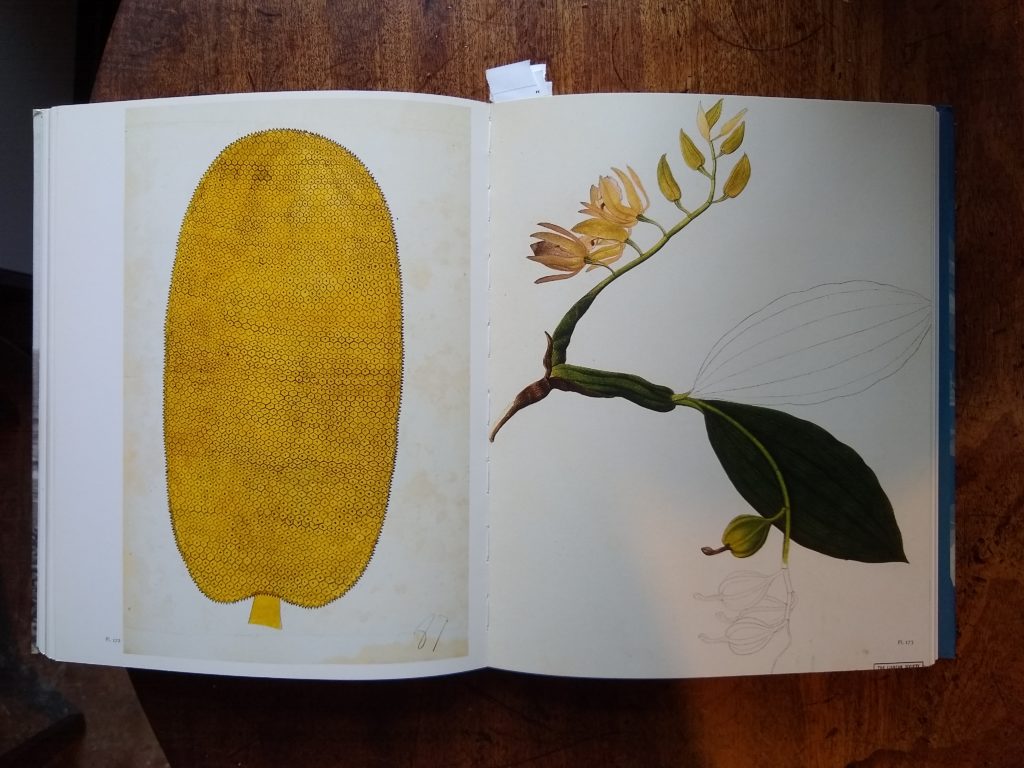

Pl. 172. Anonymous North Indian Artist, from Drawings of Indian Plants, c. 1788. Artocarpus heterophyllus [Captions of 172 and 173 reversed]. Linnean Society of London.

From an album at RBGE commissioned by James Kerr in the 1770s. Kerr wrote an unpublished monograph on the jak fruit.

RBGE, Kerr Album no. 87.

= Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.

Pl. 173. Epidendrum tricallosum. [Captions of 172 and 173 reversed]. Linnean Society of London.

Made for Francis Buchanan in Nepal in 1802/3, probably by Haludar. The collecting details given merely as ‘on trees’ in Upper Nepal.

Linnean Society of London, LS 401D/1/25.

= Coelogyne fuscescens Lindl.

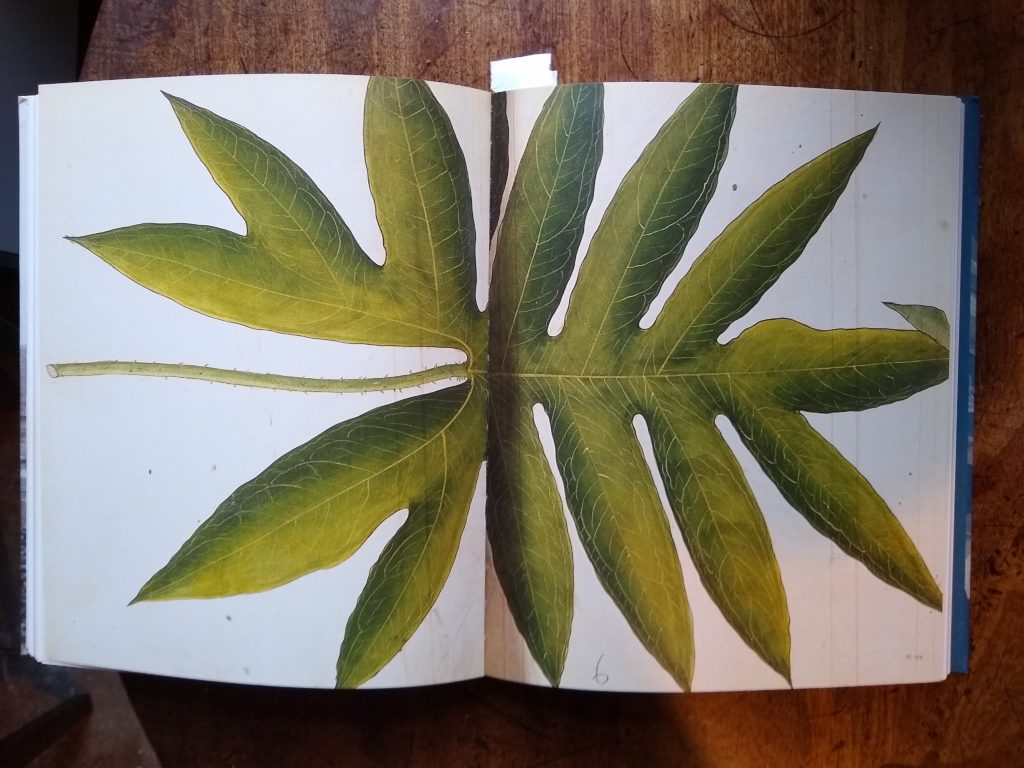

Pl. 174. [Anonymous North Indian Artist, from Drawings of Indian Plants, c. 1788]. Themeda arundinacea [erroneous label].

From an album at RBGE commissioned in Bihar and Bengal by James Kerr in the 1770s.

RBGE, Kerr Album no. 2.

= Lasia spinosa

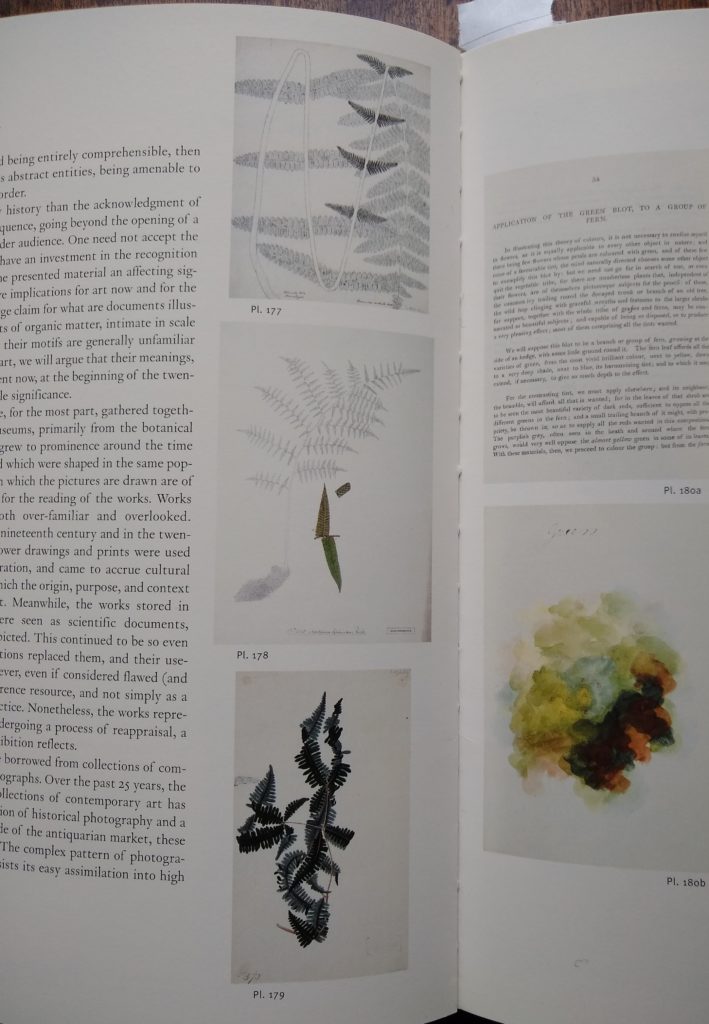

Pl. 177. Anonymous, Osmunda monticola, from Himalayas, 1880. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

From the collection of William Munro, dating from c 1845 and almost certainly by his artist Gopalchunder (one of Matonia pectinata in a very similar style dated 1846 is so labelled by Munro). Munro’s herbarium no. 2454 is cited on the drawing, but the location of this specimen is unknown, as much of the herbarium was distributed by Kew when it received his herbarium and library in 1880.

RBG Kew, no number.

= Osmunda pilosa Wall. ex Grev. & Hook.

Pl. 178. Anonymous, copy of Asplenium bipinnatum, Icones Roxburghianae, from Icones Plantarum Indiae Orientalis, 1838–53. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

The drawing is from the set of Icones commissioned by Roxburgh and sent to London (originally to the India Museum, now at Kew). As the plant was cultivated in the Calcutta Botanic Garden (from Amboyna), the drawing dates from between 1793 and 1813. See Plate 100 for explanation of erroneous reference to Wight’s Icones.

RBG Kew, Roxburgh Icones ‘2000. Asplenium bipinnatum Roxb.’.

= Diplazium esculentum (Retz.) Sw.

Pl. 179. William Roxburgh (attributed), Polypodium, date unknown. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

As suspected by J.R. Sealy in a note on the mount this is, indeed, a Roxburgh drawing. The number 573 is one of those attached by Roxburgh when sending batches of drawings to London, but this one was not incorporated into the main series of Icones. The origin of the specimen on which it was based is unknown, but as D. taiwanensis is distributed largely from Assam eastwards to China and Southeast Asia the drawing is most likely to have been made while Roxburgh was based in Calcutta, 1793 to 1813.

RBG Kew, no Roxburgh Icones number.

= Dicranopteris taiwanensis Ching & Chiu

Pl. 182. Anonymous, Polypodium lineare, date unknown. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

Annotated ‘Polypodium membranaceum Hathipaon, Aug’. One of a series of fern prints with drawings that, by comparison with drawings of flowering plants from the same locality in the Wight collection at NHM, can securely be attributed to Michael Pakenham Edgeworth. The ferns are dated only to month (August and September), but those at NHM from the same locality and from (nearby) ‘Masuri’ (= Mussoorie) the year is given as 1838.

RBG Kew, Edgeworth Collection 1.

= Microsorum membraceum (D. Don) Ching (det C.R. F.-J.)

Pl. 183. Anonymous, Untitled, date unknown. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

Nature print and watercolour details. This sheet bears no annotations, but is one of a series of fern prints/drawings made by Michael Pakenham Edgeworth around Mussoorie in 1838 (see Plate 182).

RBG Kew, Edgeworth Collection 2.

= Davallodes pulchra (D. Don) M. Kato & Tsutsumi (det C.R. F.-J.)

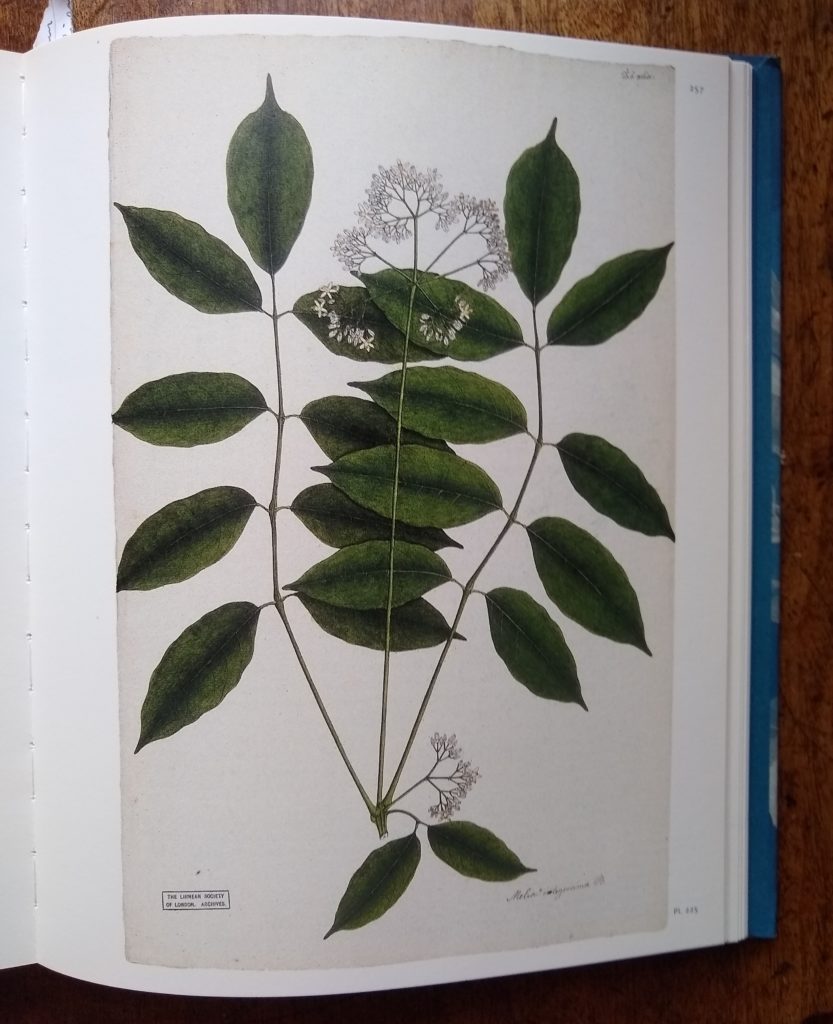

Pl. 225. Anonymous Indian artist (Collection of Francis Buchanan Hamilton), Melia integerrima, from Animalium et Plantarum descriptiones, 1802–1803. Linnean Society of London.

Made for Francis Buchanan, probably by Haludar, but on his Mysore expedition of 1800/1 and not, as stated, on the later one to Nepal. The plant was collected by Buchanan in shady forests of western Carnata (Karnataka) in May 1801.

Linnean Society of London, LS MS 402D/49.

= Heynea trijuga Roxb.

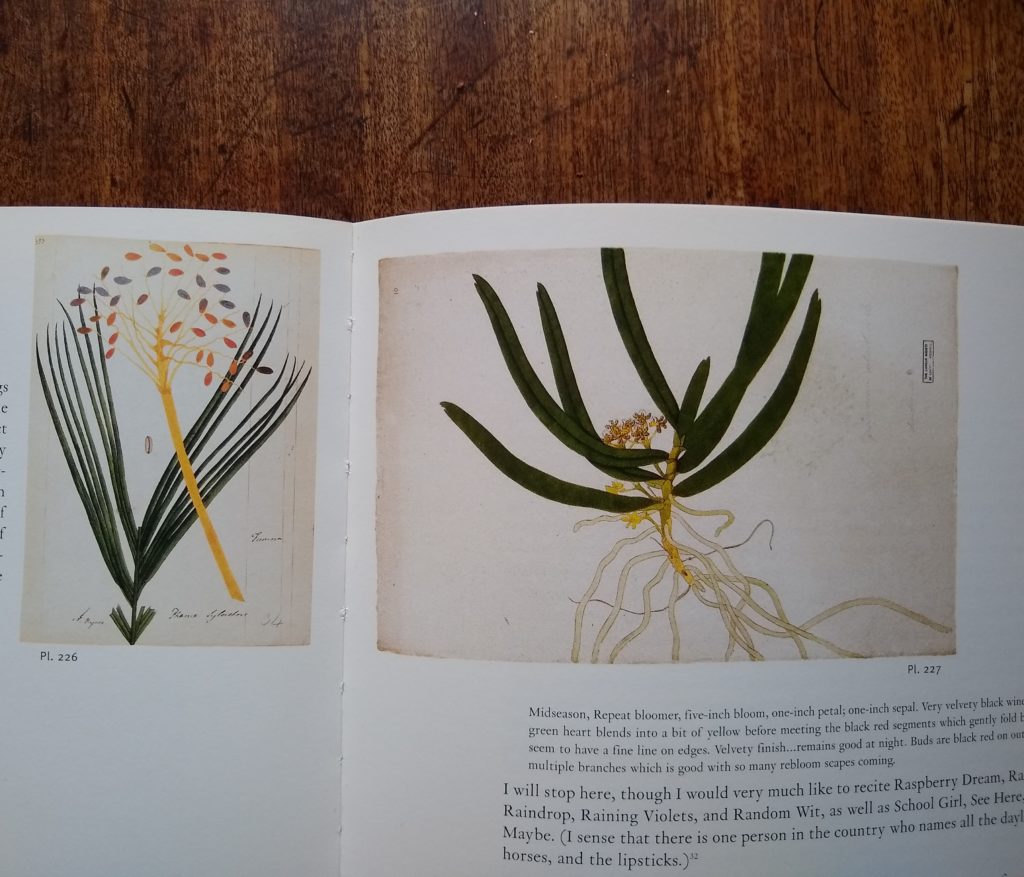

Pl. 226. Anonymous North Indian Artist, Phoenix sylvestris, from Drawings of Indian Plants, c. 1788. Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh.

From an album commissioned in Bihar and Bengal by James Kerr in the 1770s.

RBGE, Kerr Album 34.

= Phoenix sylvestris (L.) Roxb.

Pl. 227. Anonymous Indian artist (Collection of Francis Buchanan Hamilton), Epidendrum calceolare, from Nepalensium Icones Pictae, 1802–1803’. Linnean Society of London.

Made for Francis Buchanan in Nepal in 1803, probably by Haludar. At the Linnean Society is a herbarium specimen collected by Buchanan at Narainhetty, 15 February 1803. This drawing is the type of Aerides calceolaris Sm.

Linnean Society of London, LS 401D/1/21.

= Gastrochilus calceolaris (Sm.) D. Don

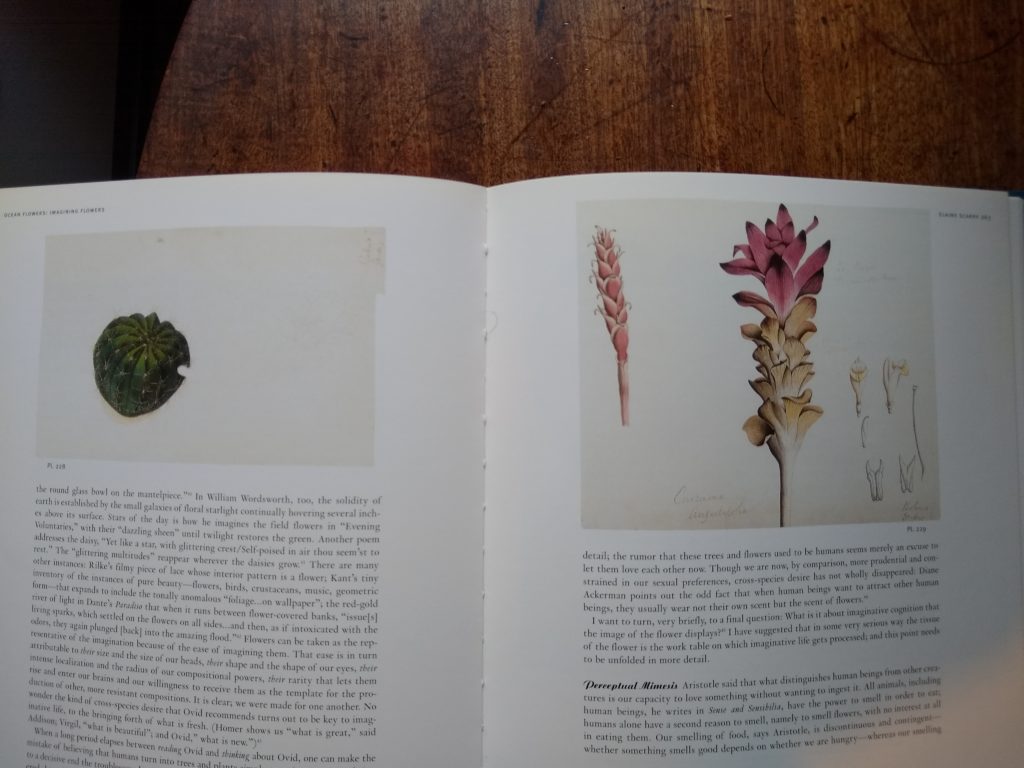

Pl. 228. Anonymous Portuguese-Indian Artist, Echinopsis cf. oxygona, c. 1848. Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh.

Without knowing the flower colour of this unfinished drawing it is impossible to be certain which species of the genus this is.

RBGE, Dapuri Drawing 128.

= Echinopsis cf. oxygona (Link) Pfeiffer & Otto

Pl. 229. Anonymous Portuguese-Indian Artist, Curcuma aromatica [Curcuma angustifolia], c. 1848. Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh.

The left-hand spike has recently been identified by the ginger expert John Mood as the little-known Zingiber neesanum, a species endemic to the Western Ghats, first described in 1839 in John Graham’s Catalogue of the Plants of Bombay as ‘Alpinia neesanum’.

RBGE, Dapuri Drawing 90.

= Zingiber neesanum (J. Graham) Ramamoorthy + Curcuma aromatica Salisb.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Christopher Fraser-Jenkins for his identification of the ferns.

References

Archer, M. (1962). Natural History Drawings in the India Office Library. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Armstrong. C. and de Zegher, C. (2004). Ocean Flowers: Impressions from Nature. New York: The Drawing Center: Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Dalrymple, W. (editor) (2019). Forgotten Masters: Indian painting for the East India Company. London: The Wallace Collection.

Noltie, H.J. (2002). The Dapuri Drawings: Alexander Gibson and the Bombay Botanic Gardens. Edinburgh: Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

Noltie, H.J. (2005). The Botany of Robert Wight. Ruggell, Liechtenstein: A.R.G. Gantner Verlag.

Noltie, H.J. and Watson, M.F. (2019). The Buchanan-Hamilton collection of botanical drawings at the Linnean Society of London. In: Sita Reddy (editor) The Weight of a Petal: Ars Botanica, Marg vol 70 (2): 81–4.

Santhosh Kr. Sakhinala (2019). The Roxburgh Icones in the Kolkata Botanic Garden. In: Sita Reddy (editor) The Weight of a Petal: Ars Botanica, Marg vol 70 (2): 64–7.

Sealy, J.R. (1956). The Roxburgh Flora Indica drawings at Kew. Kew Bulletin 1956: 297–348; 349–399.

Sterll, M. (2022). Nathaniel Wallich: global botany in nineteenth-century India. New Delhi: Manohar.